Psychotherapy is an art that we insist, for the best of reasons, on treating like a science. The relationship between therapist and client, if it's working, should have a controlled volatility; the rules -- ethics, methods -- are like the bars that make it possible to stand a few yards away from a panther and feel perfectly safe.

Nevertheless, the official pop culture view is that psychotherapy is too rational, too pat in its confidence that it can bring order and progress to the roiling depths of human emotion. So, in the movies, shrinks tend to do one of two things that are strictly against the rules: They sleep with their patients, or kill them.

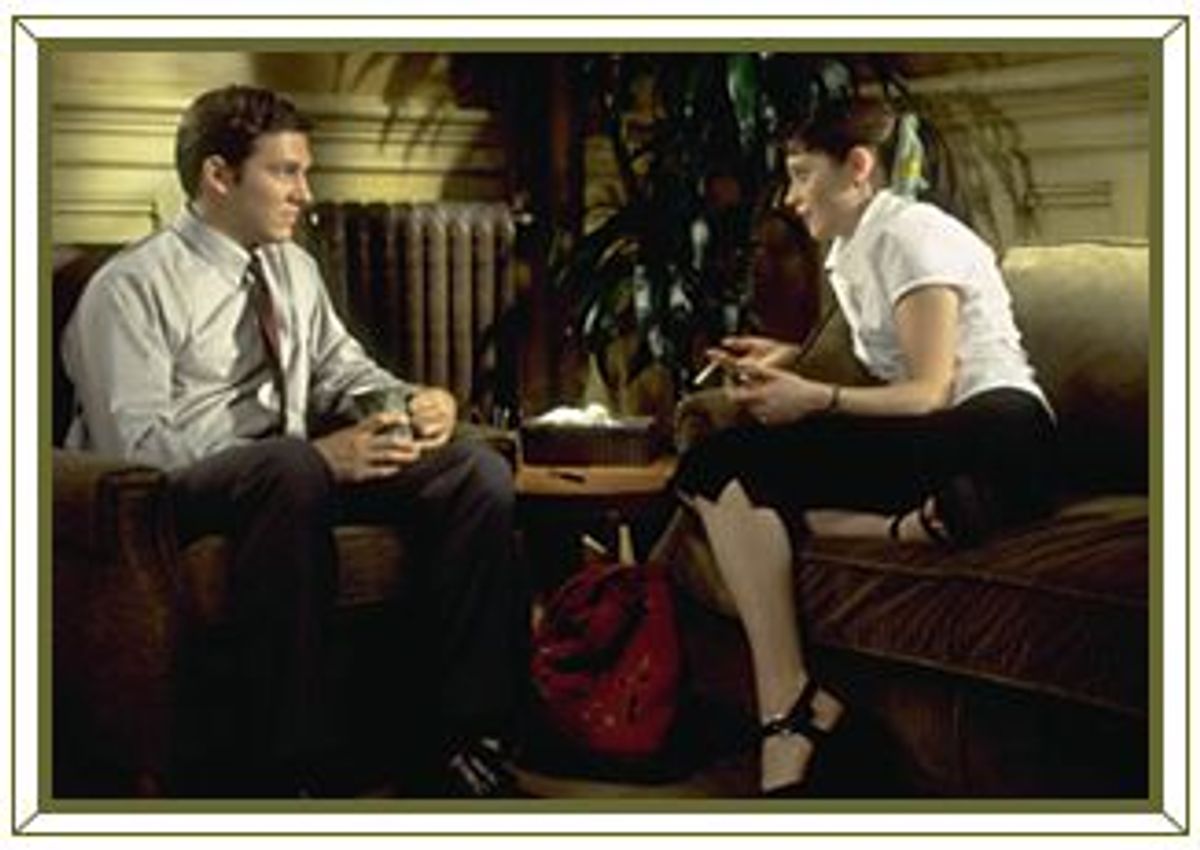

The psychologist in Lawrence Kasdan's new film "Mumford" manages not to do either. (He does fall in love with one of his patients, but decides to stop treating her before professing his feelings.) Mumford (Loren Dean) confronts a pretty formidable ethical conflict nonetheless; he breaks the rules every time he treats anyone because he's not actually a licensed therapist at all. In fact, his real name isn't even Mumford.

The point of Kasdan's low-key but winning ensemble comedy is that training is no match for native talent, something Mumford has in spades. We learn at the beginning of the film that he's only been in town four months and already he's out-pulling the other two psychologists there. (When this pair turns up later in the movie they're delightfully subtle variations on the usual nutty shrink stereotypes: she's a high-strung pleaser and he's an egghead who harps on death. "The skull will grin at the banquet!" he crows merrily over cocktails.) Mumford's unconventional treatment methods -- he takes a chronic fatigue syndrome sufferer out on a paper route and ejects patients when they get on his nerves -- seem to really work, and he's "shockingly honest," as his inamorata, Sofie (Hope Davis), puts it; he describes her mother, accurately enough, as a "bitch."

But Mumford's unconventionality is problematic -- this isn't one of those cloying message movies like "Patch Adams," in which a big-hearted rebel bucks the cold, clinical establishment and makes a long, sappy speech at the end to the tearful appreciation of a frighteningly large percentage of the American public. Mumford blithely offers one client, a sweet young technology billionaire (Jason Lee) who has to pretend that he's just palling around with the psychologist to avoid freaking out the stockholders, a lengthy disquisition on the sexual fixations of another -- a chubby, balding pharmacist (Pruitt Taylor Vince) with a fantasy life right out of "The Postman Always Rings Twice."

Movie shrinks have tended to be extreme examples of either saintly miracle-workers (like Barbra Streisand in "The Prince of Tides") or dangerous, even fiendish frauds (like Michael Caine's murderous transvestite analyst in "Dressed to Kill" or the child molester in Todd Solondz' "Happiness.") For other filmmakers, therapy is a subculture of easily parodied rituals -- the joke of "Analyze This" hangs on the clash between the formalities of organized crime and the protocols of the couch, both strategies for distancing oneself from an essentially messy business. But the majority of movie therapists don't rate highly enough to be characters at all. Most cinematic psychologists simply provide an excuse for characters to explain the kinds of inner conflicts and conditions that movies have always had trouble getting across through purely visual means. Often, as with Anne Heche's character in the 1996 independent film "Walking and Talking," the therapist seems profoundly alien, a dowdy, prosaic emissary from a tiresome planet where everyone talks too much and people's looks don't tell you everything you need to know about them.

That may well be because psychotherapy has always been a literary profession. The best shrinks are often terrific writers -- in fact, some of them (like Freud) are better at writing than they are at healing. Indeed, the traditional Hollywood vision of the therapist -- occasionally a savior, sometimes a monster, but usually a convenient if peripheral tool -- has a lot in common with the industry's attitude toward its writers. And how vexingly uncinematic both writing and therapy are: They're static and wordy, and they seem to take forever.

So it's not surprising that "Mumford," which features one of the rare complex portraits of a therapist (albeit a bogus one), is a very writerly movie. The screenplay has been as carefully crafted as a story coming out of the Iowa Writer's Workshop. It's never obvious and it trusts its actors and its audience enough to not belabor its points. When the exhausted Sofie makes a passing reference to a time when "I used to exercise too much" or when Skip, the billionaire, briefly mentions wishing he'd made the varsity team, Kasdan creates the sense of whole lives lived before the action we're seeing onscreen.

The performances, uniformly deft and thoughtful, all show the same light touch, from Lee's immensely winning Skip Skipperton, a skateboarding wunderkind who's naive, but far from stupid, to Mary McDonnell as a slightly dotty matron with a monstrous husband, a serious addiction to mail order and smoldering reserves of sensuality. Dean, who acts as the straight man amidst it all, has to get by with an impassive expression (he's one of those guys people just naturally confide in, so this makes sense), but Kasdan has given him plenty of edgy lines to play off that bland face and the effect is piquant. And then there are dozens of artful details -- for example, Skip's company is called Panda Modem, a name so perfect I'm surprised it isn't already being used in Silicon Valley.

"Mumford" is a movie full of insightful moments, and some of them are even pure therapy. Zooey Deschanel plays another patient, an anorectic girl who's obsessed with the world she sees depicted in fashion magazines but willing to consider Mumford's suggestion that she learn to accept that some things just aren't going change -- including her own body. "How depressing is that," she sighs, "the moment when you give up?" Her despair is palpable, and handled respectfully. But most veterans of the couch can recall reaching such a turning point, one that feels precisely like defeat even though it's actually the glimmer of new possibility.

Shares