A friend once described opium to me by explaining how it made him feel both

drowsy and intensely, sensitively awake. That's how I'd describe the

opening shots of Tim Burton's "Sleepy Hollow," a movie that begins working

its visual seduction from its earliest images: a pool of sealing wax

spilling onto a piece of paper like crimson blood; a carriage rambling

through a countryside rendered diffuse in smoky blue light. The look

of Burton's Gothic dream landscape, both lulling and energizing, is vested

with so much power that it could almost substitute for narrative drive.

With each successive image, I found myself asking, "What's going to happen

next?"

In Burton's loose, highly stylized re-imagining of Washington Irving's "The

Legend of Sleepy Hollow," Ichabod Crane (Johnny Depp) isn't a knobby,

awkward schoolteacher but a constable who's prone to rather

dignified-looking bumbling. The story opens in 1799 New York: Ichabod has

been assigned to investigate a number of horrific murders upstate, in which

people's heads have been lopped off (with a fire-hot sword, no less) by the

Headless Horseman. The Horseman was formerly a ruthless Hessian mercenary

(played in the flashback sequences by a deliciously deranged Christopher

Walken) who'd been beheaded and plopped into a sloppy grave by

Revolutionary War soldiers, and who now haunts the nearby wood doing his

dirty work.

Crane -- who keeps his painfully obvious observations in a beautifully

illustrated and calligraphic book, a symbol of his yearning to mask his

inadequacies with pure style -- doubts that the Headless Horseman is really

a ghost and begins to suspect that the town elders are somehow involved.

Meanwhile, he also faces recurring nightmares based on his own childhood

trauma, as well as a burgeoning attraction to a young woman of the town,

Katrina Van Tassel (Christina Ricci), who dabbles in witchcraft.

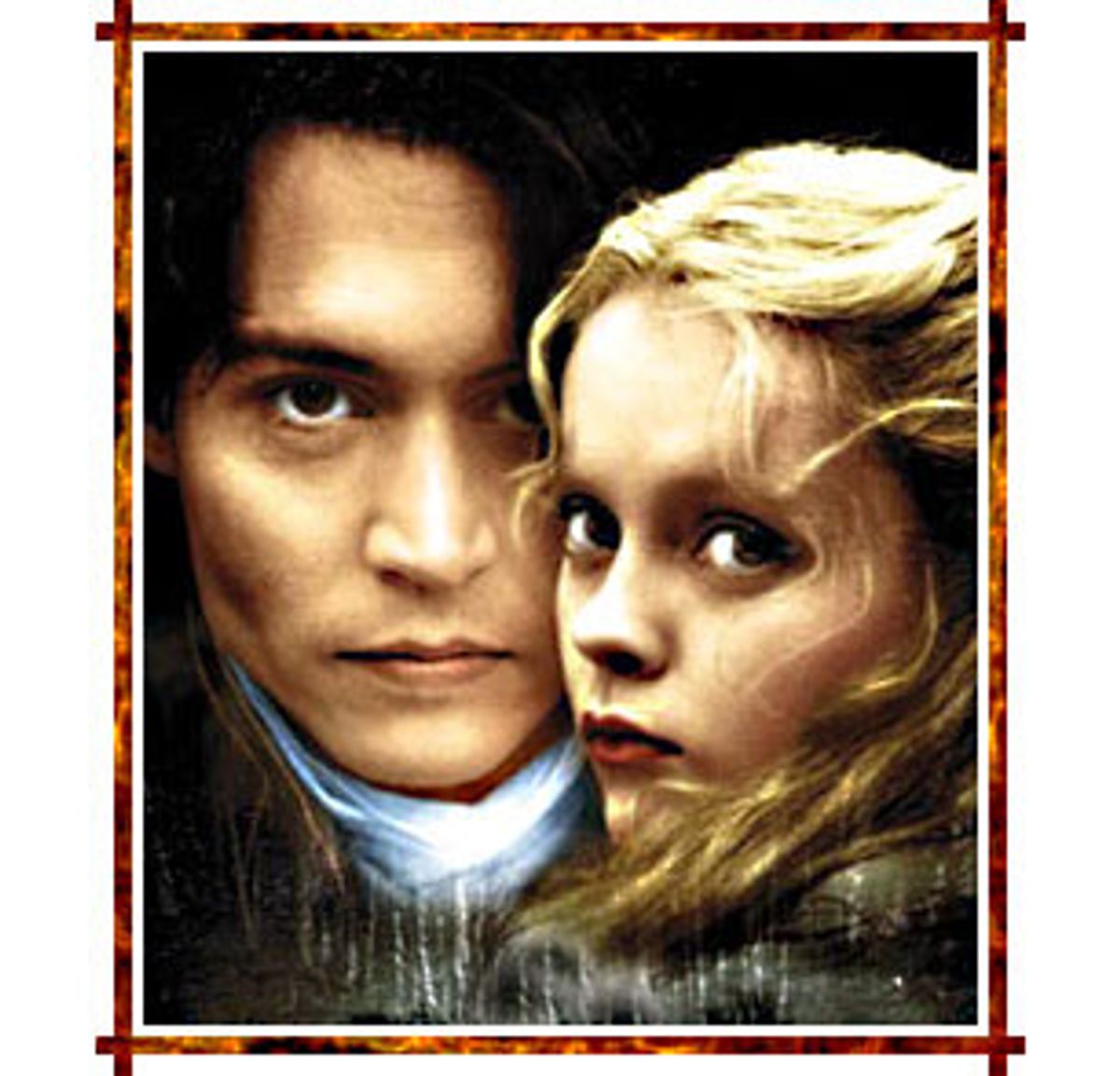

Depp isn't Irving's Ichabod Crane, but it hardly matters. With his

translucent, silent-film-star skin and lovely hollowed cheeks, this Ichabod

is a tortured, if not terribly bright, goth dreamboat. Depp gives even his

awkward, clueless stabs at scientific observations an almost debonair

quality. And the way he hides behind his young friend and helper (Marc

Pickering) in times of terror plays up his endearing fragility. Depp's wit

and cunning are nicely understated here, lurking just beneath his somber

black topcoats and high, winged collars. His stammering and fake-confident

strutting give the movie just a touch of brightness, without disturbing its

brooding undertones.

Ricci suits Depp nicely as the inscrutable and luscious Katrina: she's both

a quiet sexpot, capable of ruffling the rather straitlaced Ichabod's

feathers, and a mysteriously calming presence. (In one scene, she meets

Ichabod in the wood, astride a white horse and draped in a white cloak

embroidered with red roses; the sight of her is simply breathtaking.)

Miranda Richardson as Lady Van Tassel, Katrina's stepmother, is crisply

enjoyable, and her bald-eyebrowed look alone is a source of weird

fascination. Burton has a knack for choosing the right look for each

character -- think of the way the bruised-looking, sleepless-night eye

makeup Depp wore in "Edward Scissorhands" seemed to underscore the

character's essential conscientiousness -- and he uses those skills

beautifully here.

Burton also has a keen eye for casting. As the town elders, Michael Gambon,

Richard Griffiths, Jeffrey Jones and Michael Gough all have that perfect

look of depraved authority. And in a witty homage to Hammer horror films, he's cast Christopher Lee as a stonily severe judge.

The plot falls short on discernible logic now and then, but that's hardly

an issue. "Sleepy Hollow" is all about visuals, music and mood, about being

swept away by what's on the screen. Danny Elfman's music is haunting and

jaggedly elegiac, the perfect underpinning to the movie's look.

Cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki brushes nearly every frame with a bluish

cast: This Sleepy Hollow is a wonderland of misty coolness, of horizons

defined by craggy trees, of shaded woods holding tight to their secrets.

The Horseman himself is a magnificent and horrifying creature, galloping

out from the maw of nowhere, his sword brandished like a warrior's spear,

his cape floating around him like malevolent squid ink.

And since this is a Tim Burton movie, it only figures that latent childhood

fears should figure prominently. "Sleepy Hollow" has an R rating, although

the cartoonishly grisly flying heads aren't particularly distressing (and

overall, the movie is nothing like its mean-spirited predecessor "Mars

Attacks"). What makes "Sleepy Hollow" so adult and finally so indelible is

the gorgeous, spellbinding quality of its nightmare visions; these

terrifying dreams are imbued with an almost tranquilizing beauty. A

youthful mother lights a revolving lantern for her young son, sending

visions of witches on brooms and spooky goblins swirling around the walls.

Yet the sequence isn't played for creeps -- if anything, there's more a

sense of wonder to it than anything. Ichabod's visions of his own beautiful

young mother are softly shaded, shimmery, tinted with vaguely erotic

undertones like those old-fashioned hand-colored photographs. She whirls in

a garden, her dress fanning out like a pinwheel of water around her,

calling his name. The delight in the child Ichabod's eyes as he watches her

is so complete that you know for sure he's going to lose her -- and he does.

But Burton is possessed of an extremely delicate touch. While I wouldn't

recommend "Sleepy Hollow" for kids, I wouldn't hesitate to vouch for

Burton's integrity in terms of the way he deals with the fears of his

adult audience. So much of the movie is lovingly devoted to those

fears. Burton doesn't play them cheaply, or to grab at heartstrings;

instead he lavishes tenderness on them.

Children don't need to have their fears examined (plenty of time for that in adulthood). But grown-ups, busy living life, making money and raising kids of their own, tend to make the mistake of coddling their inner child, if they pay any attention to it at all. In "Sleepy Hollow," Burton sees the inner child as a small adult, like the ones you find in 18th century American primitive paintings, earnest toddlers wearing tragically grown-up clothes while clutching kittens or toy hoops. It's a way of conferring respect and a kind of dignity on the spiritual life of children, instead of treating it as something sweet and simple and eventually outgrown. Burton keeps in direct contact with it himself, and for the rest of us, he's an able guide. The other side of the looking glass lies just beyond his camera lens. All we have to do is keep awake -- and step through.

Shares