It must be hard to misread the tone of a book as single-minded as Patricia Highsmith's "The Talented Mr. Ripley," but Anthony Minghella manages somehow. Minghella has filmed Highsmith's nasty classic of homicidal paranoia in the deluxe style he used on "The English Patient" -- all tasteful creaminess, like an expensive dessert cart presented by a discreet waiter. The characters can't get into a boat without Minghella's first giving us an eyeful of postcard-

As Highsmith begins the story of Tom Ripley in the first of the five books she featured him in, he's riding out a New York autumn, vaguely taking advantage of a circle of contacts whose means are far above his while working scams almost as an amusement. He meets up with the father of a spoiled rich acquaintance named Dickie Greenleaf, who has decamped to Italy with dreams of being an artist. (Minghella makes Dickie an aspiring jazz musician.) Dickie's mother is ill, and his father, who wants him back, offers to pay Tom's fare to Europe, plus expenses, if Tom will try to persuade Dickie to return. Pressing this tenuous connection, Tom travels to Italy and inserts himself into Dickie's life, precipitating a rift between him and his girlfriend. When it becomes clear that Dickie has no intention of going back -- and that his recalcitrance will mean the end of the good life Tom has settled into -- Tom methodically plans Dickie's murder, executes it and takes over Dickie's identity. After the murder, Highsmith shows Tom living as Dickie and, when that becomes impossible, transferring Dickie's riches to his own coffers.

In outline, the book sounds like a noirish parable of class resentment -- and Tom, who has been brought up in shabby circumstances by an unloving aunt, is certainly eaten up with envy over the money and the opportunities Dickie takes for granted. But that envy is Highsmith's pretext for rooting around in the mind of a coolly detached psychopath. Tom is running deceptions and con games and screwing with people's minds long before he gets a chance at Dickie Greenleaf's money. (And he continues doing so in the books that follow, long after he is able to take the good life for granted.)

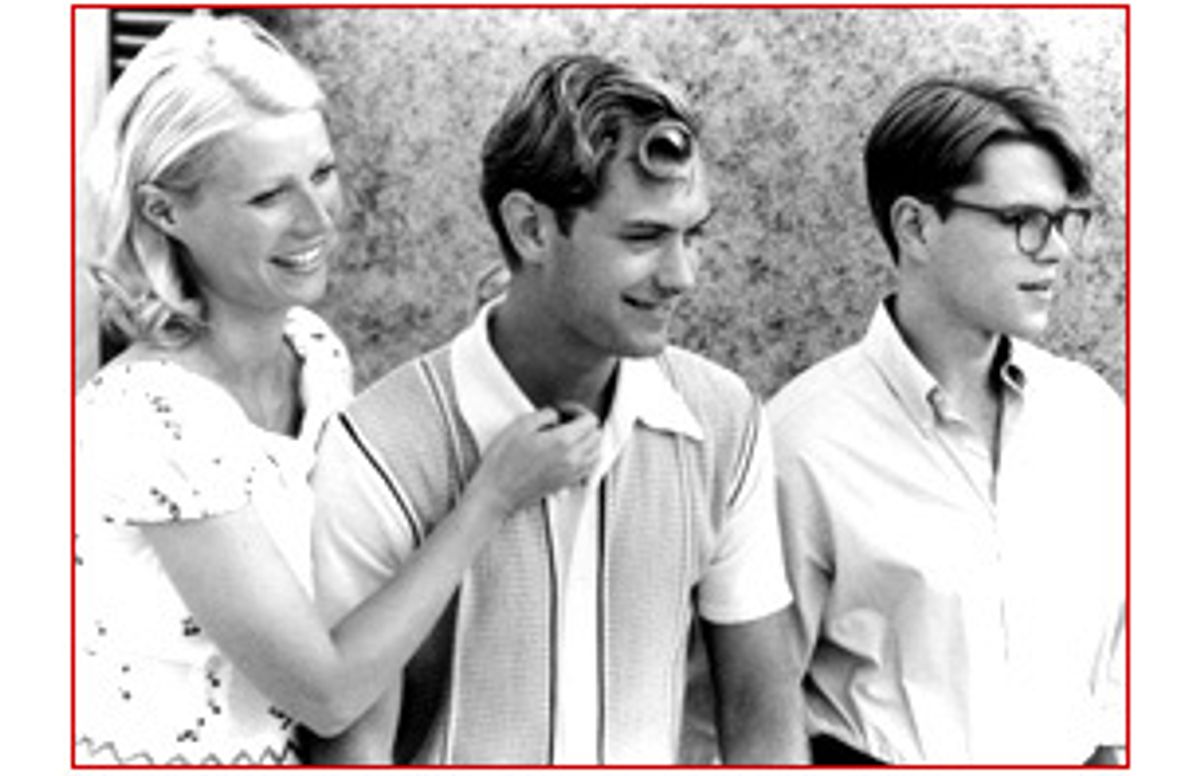

Minghella must have envisioned Tom as something like a murderous version of Montgomery Clift's George Eastman in "A Place in the Sun." As played by Matt Damon, Tom is the kid who's got everything going for him but money. His charm and good looks and good manners allow him to fit in easily among people who, if they knew his background, wouldn't give him the time of day. In adapting the novel, Minghella has made Ripley both nice and pitiable. When he kills Dickie (Jude Law), it's purely on impulse -- he's only reacting to Dickie's hurtful remarks about his being a leech. It doesn't seem to occur to Minghella that he is a leech; in the book, Dickie's girlfriend, Marge, picks up on the creepy way Tom gloms onto Dickie (not to mention Tom's attraction to Dickie), but Minghella misses it.

He does add a few fancy touches meant to convey Tom's splintered personality: the literally splintered views of him in the title sequence (so reminiscent of the work of movie titles designer Saul Bass); a shot of Dickie's face while Tom is saying, "This is my face"; a later shot of Tom's head above the top of a standing mirror in which Dickie's body is reflected. But for much of the movie, Tom is just an awkward kid given the chance to lead the life of Riley (we even get to see him crying at the opera) and then cruelly shut out when he ceases to amuse Dickie -- and when Dickie becomes embarrassed by Tom's presence among his posh friends.

Part of what makes the movie so ridiculous is the casting of Damon, who has the world-beater smile and high-WASP good looks that naturally belong to the type of well-bred guys Tom Ripley tries to emulate. Having Damon hide behind a pair of horn-rimmed glasses doesn't change any of that. Tom needs to be soft and seemingly weak, so that when we pity him we become the butt of his joke. (Tobey Maguire could have hit this role out of the park.) Damon's sudden, accurate impersonations are startling (at one point he directs an impression of someone he's just killed to the corpse), but he simply comes across as too stable and sturdy to suggest the quavering sickness of Ripley.

As Dickie and Marge, Jude Law and Gwyneth Paltrow look right, and their behavior -- Dickie's alternating patrician reserve and boorishness, Marge's absolutely impersonal solicitude -- feel right. But the characters aren't that interesting, and the casting of Paltrow is particularly infelicitous. Paltrow has a ways to go as an actress, but she can be a charming presence. Here, though, Minghella seems to have cast her solely for her golden-girl air, and though he's made Marge smarter than Highsmith's somewhat misogynist portrait (her Marge is something of a cow), he seems -- inadvertently -- to be saying the very thing Paltrow's detractors say: that there's not much to her beyond her looks.

As a textiles heiress who becomes smitten with Tom (a role invented by Minghella), Cate Blanchett gets to kick up her heels a little more. At first she seems to be laying it on a bit thick, but her Meredith does lay it on thick, and Blanchett projects an almost girlish charm behind the artifice. As Dickie's caddish friend Freddy Miles, Philip Seymour Hoffman zooms in driving a red convertible and pretty much walks off with the movie in his pocket.

Hoffman's Freddy has a frat-boy grossness that belies his wealth, and an arrogance beyond what his brains or looks should allow for. He gets away with his bad behavior because he has the money to get away with it. It's always startling to see an actor capture a type you've encountered in life but never seen on film, and Hoffman's gusto gives the movie the dose of dirt it so desperately needs.

Patricia Highsmith's admirers have long argued that she is much more than a genre writer. I'm not convinced. In "The Talented Mr. Ripley" she wrote a damn compelling novel, but I don't find her chill, rancid misanthropy pleasurable. Still, it's easy to see why filmmakers are attracted to her combination of nastiness and swank. The trouble is that the pretty/kinky surface seems to blind potential adapters to this book's booby traps.

"The Talented Mr. Ripley" isn't a mystery (we're never in doubt as to what's happened), and it's not really a thriller. It's an arm's-length dissection of the personality of a psychopath, and in movies that distance translates as coldness. The temperature didn't matter much in Rine Climent's 1959 adaptation of the novel, "Purple Noon" (featuring French cinema's great tabula rasa, Alain Delon, as Ripley) because Climent presented the life of the decadent rich with an unabashed whorishness. (It was an honestly voyeuristic version of the lifestyle Antonioni and Resnais would spend the next decade clucking over.)

But Tom isn't a psychopath who invites feelings of recognition or even protectiveness the way that a warmer though much more extreme character like Norman Bates can. Maybe because on some level Minghella recognized that, he set out to make us share in Tom's culpability. The director softens everything about the book, then ladles on prestige production values. To his credit, he seems to have little patience with the old notion -- which Highsmith subscribed to -- of repressed homosexuality as a metaphor for aberrant behavior. (And Highsmith was a lesbian.) Though Minghella is more open about Tom's sexuality, his presentation of it still feels held back; he's hesitant about making it just one more part of Tom's splintered psyche. And while he doesn't tack on the moralistic ending with which Climent closed "Purple Noon," his jiggering with Highsmith's carefully worked-out plot results in something that, in its own way, feels nearly as moralistic.

"The Talented Mr. Ripley" is a film made by a man who is uncomfortable with the material he has chosen to adapt. Watching this sluggish, uninvolving picture, too carefully made to be obviously bad, too steeped in quality to offer visceral thrills or sensual pleasure, recalled for me the feeling of watching "The English Patient."

Paralyzed with respect for the dried-out floweriness of Michael Ondaatje's prose, Minghella treated a soapy wartime romance (albeit one that asks you to weep over a Nazi collaborator) as a profound tragedy. Here he treats a mean, squirrelly little book as a major statement on class envy and the dissolution of personality.

"The Talented Mr. Ripley" is, in a way, a predictable failure. Having earned the kind of praise he did with "The English Patient," Minghella isn't going back to the modest style and the organic emotion of "Truly, Madly, Deeply," his first and still his best film. It's even more depressing to see these glamorous young stars sealed up in a the kind of glossy prestige picture whose boring refinement works against the very idea of star power. In a weird way, Minghella has remained true to Tom Ripley's fantasies: He's made a movie that is killingly tasteful.

Shares