Philosopher Hannah Arendt coined the phrase "the banality of evil" in discussing the career of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi bureaucrat who was one of the principal engineers of the Holocaust. In recent years, this concept has become controversial -- New York Observer columnist Ron Rosenbaum, for example, has argued in his book "Explaining Hitler" and elsewhere that evil on the scale perpetrated by the Nazis cannot be understood in such terms. Still, the phrase continues to resonate throughout our culture, and it's impossible to watch Errol Morris' chilling new documentary, "Mr. Death: The Rise and Fall of Fred A. Leuchter, Jr.," without considering it.

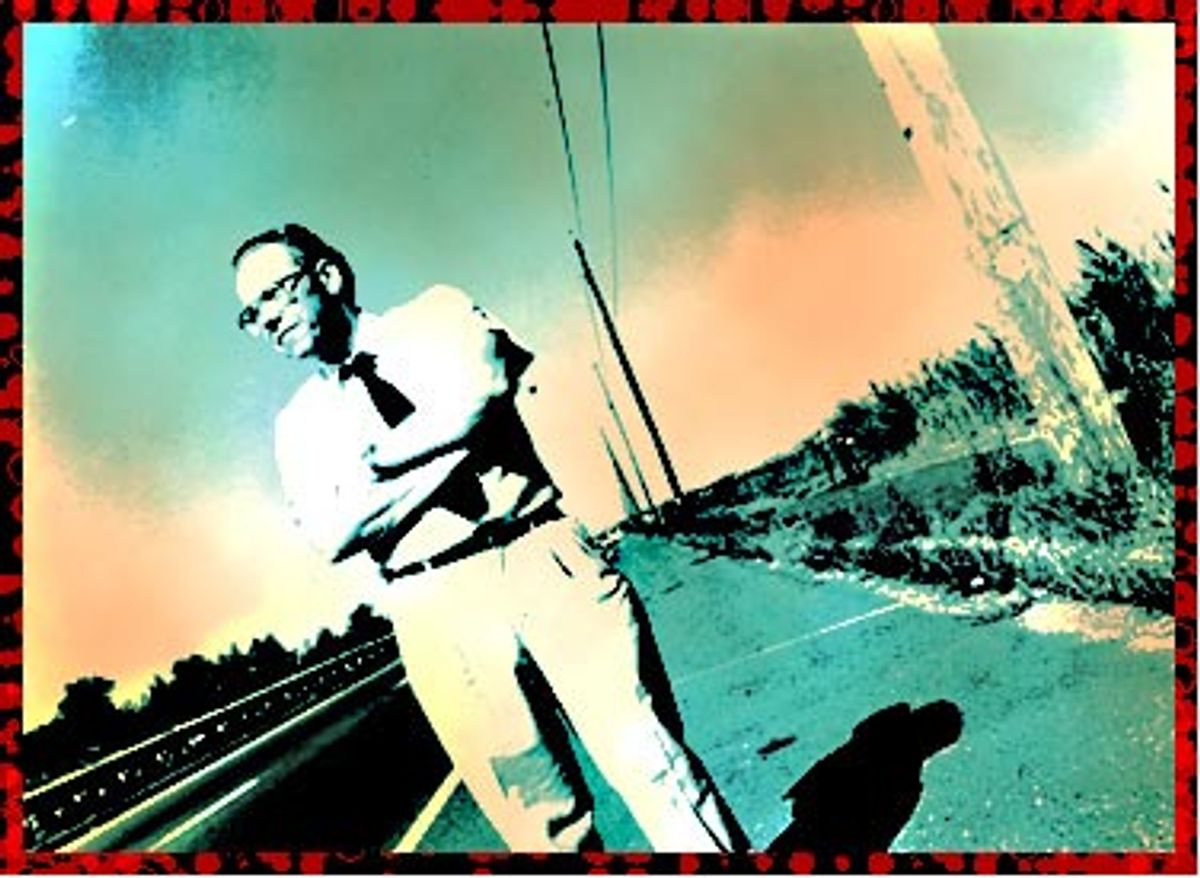

Leuchter is another of the eccentric characters who fascinate Morris, but unlike the mole-rat expert, robot designer and lion tamer Morris portrayed in "Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control," Leuchter's journey goes beyond the realm of pathetic or quixotic obsession into ugliness and darkness. Maybe this story about a lonely American engineer with no evident ideology who became a lightning rod for Holocaust revisionism can best be described as a fable about the evil of banality.

Long before he became a hero to neo-Nazis around the world by "proving" there were no gas chambers at Auschwitz, Leuchter (which he pronounces LOOT-cher, rather than the Germanic LOYCH-ter) was already a morbid oddball. A small-time engineer whose father had been a Massachusetts prison guard, Leuchter had carved out a professional niche as a designer and refurbisher of execution equipment. As gruesome as this may be, Leuchter is quite correct in saying that if our society is to practice capital punishment someone will have to do it. He initially became involved, he insists, out of humanitarian concern, upon learning that the antiquated electric chairs used in North Carolina and Tennessee "normally resulted in torture prior to death." If the current is insufficient or incorrectly administered, it might take 35 or 40 minutes for a condemned person to die. On the other hand, as Leuchter reports in his thick Boston accent, too much voltage may be used, in which case "the meat comes off the executee like meat off a cooked chicken."

His success with electric chairs led to contracts for automatic lethal-injection devices (so that a doctor would not have to administer the injections) and even for gallows. As Leuchter wryly points out, there is no connection between these devices beyond the fact that they're used to kill people. But as state after state reinstituted the death penalty and began to apply it, authorities needed someone to call who could build efficient, modern equipment that got the job done. "It's not a major market," as Leuchter says, but it was his. He is proud of his fair pricing (no more than a 20 percent markup!) and of his innovative design features: automobile-style safety belts, to make corpse removal easier; a drip pan under the chair, to minimize embarrassment and keep highly conductive urine off the floor of the death chamber.

By the time Leuchter got a call from the lawyers for Ernst Z|ndel, a neo-Nazi facing trial in Canada for disseminating Holocaust-denial propaganda, he had already become a low-rent entrepreneurial answer to the German engineers who designed the death camps -- a practical-minded man who saw a need and filled it. As he blandly explains for Morris' camera, there is no difference between a life-support machine and an electric chair, except that if the former fails you die and if the latter fails you live. Not even the most ardent opponent of the death penalty would argue that building machines for the execution of criminals is morally equivalent to designing genocide camps, but from an engineering standpoint, the only differences are questions of scale and degree.

When the movie suddenly touches down at Auschwitz for a few minutes before leaving again it runs the risk of being dwarfed by what it encounters there. Certainly the comic-horrific scenes in which Leuchter -- swaddled in goofy winter clothes like a science nerd on a fifth-grade field trip -- bumbles around the ruins of gas chambers and crematoria, hammering illicit "samples" out of the walls while intoning a pseudo-scientific narration to the camera, are not easy to tolerate. But why should they be? Morris is making the point, I think, that Leuchter is so incapable of relating to other people that the ruins of an extermination camp -- like the electric chairs and lethal-injection machines he designs -- are for him nothing more than an engineering problem, a forensic puzzle.

In Leuchter, Z|ndel had accidentally found the perfect stooge, a man who believed deeply in technical expertise and who could convince himself that his skill at building electric chairs in his basement made him an expert on something. With no knowledge of German, of Holocaust history or of World War II in general, he could spend a single afternoon stealing rock samples from decaying 50-year-old buildings and shock the world with his conclusions. As historian Robert Jan van Pelt puts it, "Leuchter is a victim of the myth of Sherlock Holmes." Leuchter's own impressions of the time he spent in a place where perhaps half a million people died are those of a teenager after a visit to the town cemetery: "It was cold, it was wet, it was kind of spooky."

As Morris makes clear, Leuchter's "findings" that the bricks at Auschwitz bear no traces of cyanide gas were amateurish nonsense with no scientific or historical merit. Ironically enough, they destroyed his career as a supplier of death machines as well as his marriage, but they briefly made him a beloved celebrity in the fringe world of Holocaust revisionism. The most painful and pathetic moments in "Mr. Death" come when we see Leuchter appearing at a series of revisionist conferences, grinning from ear to ear and virtually effervescing with happiness at finally having become one of the popular kids. Briefly, this becomes the story of a guy who wanted love and found it in the strangest of places. But ultimately, even neo-Nazi wacko loser movements have their rejects. British historian David Irving, an intellectual leader in Holocaust revisionism, superciliously observes that Leuchter was only an accidental hero, an innocent simpleton who blundered briefly onto greatness. "He came from nowhere," Irving sniffs, "and went back to nowhere."

Like all of Morris' films (which also include "The Thin Blue Line" and "A Brief History of Time"), "Mr. Death" is a strange piece of work, perhaps closer to an imaginative portrait or an experimental fiction that borrows elements from real life than a traditional documentary. We have no sense of time frame and very little of geography; Morris is more interested in arty close-ups of Leuchter's speedometer or his percolator than in telling us whether his bizarre odyssey unfolded over the course of six months or 10 years. We bounce around from Boston to Tennessee to Auschwitz to Toronto to Southern California, from archival color video to jittery black-and-white film. For reasons I think I half-understand but cannot quite articulate, we watch a horrifying film of an elephant being electrocuted, made by Thomas Edison in 1903.

Similarly, the tone of "Mr. Death" is highly unstable. My guess is that this is partly deliberate and partly not; Morris knows that Leuchter is at best an arrogant and misguided idiot, but when he sees a weirdo with bad teeth in a cheap suit he wants to like him. If David Lynch put Leuchter in a movie you wouldn't believe him. By his own admission he drinks 40 cups of coffee and smokes six packs of cigarettes a day, and he apparently believes that the state of Tennessee's electric chair (which he lovingly refurbished) is haunted. At certain moments, you may not be able to help feeling pity and even something like compassion for Leuchter, if only because his desire for human affection seems so naked and his capacity for it so crippled.

Shares