There's just enough genuine grit and spirit in "Girlfight" to keep it from being knocked to the canvas by indie earnestness. Writer-director Karyn Kusama, making her feature debut, flirts with the notion that, in the movies, dreariness equals integrity and authenticity. And I'd guess she was encouraged in that view by the film's executive producer, John Sayles, the indie eminence who has never really learned how to make a movie.

The odd thing about "Girlfight" is that, in what it says about boxing as a means of achieving dignity and making something better of life, it's not that far from "Rocky." That's a comparison that would probably appall any self-respecting indie devotee. Even though it was made within the studio system (for United Artists) "Rocky" was, in spirit, the quintessential indie movie that turned Hollywood heads. Made for less than $1 million by an unknown writer-star, and gritty in a way that didn't look like the usual Hollywood version of grit (the crummy apartments of Sylvester Stallone's characters were really crummy), it was an underdog story that allowed you to feel good for its characters without feeling like your head had been stuffed with cotton.

I raise the comparison not to knock indie movies but to point out the self-defeating contradiction of movies that are basically crowd pleasers but won't avail themselves of the energy that would make them emotionally satisfying. A little more flair and polish could have made "Girlfight" a terrific movie instead of just the decent one it is. A new director should be allowed time to find her feet, but the best part of Kusama's work suggests she's a better director than she allows herself to be here.

The best thing the movie has going for it is a subject that's both engaging and touchy. Women's boxing is one of those things that periodically remind us just how much or how little we believe in equality between the sexes. Sure, there are traditional fans who are sometimes appalled by the very idea of women's boxing. But there are feminists who are just as appalled, who think that women who box are allowing themselves to be co-opted by male aggression. (In her new book, "The Boxer's Heart," writer and boxer Kate Sekules quotes a female boxing publicist as saying, "I don't want to deny any woman the right to do what she wants, but I don't really want to promote it. Maleness is a vital component of boxing.")

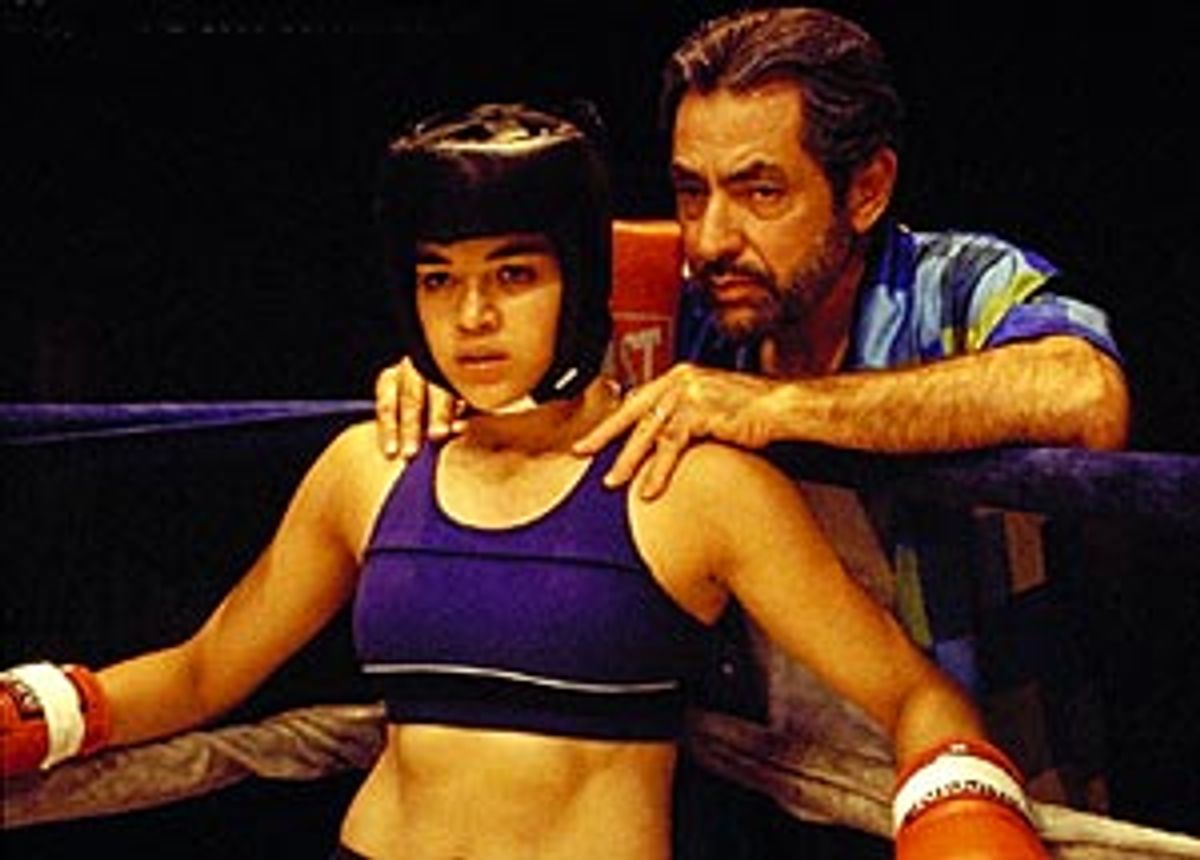

There's a trace of that view -- boxing as solely male aggression -- in "Girlfight." In the gym and in the ring, Kusama's heroine Diana (newcomer Michelle Rodriguez) is working off the anger she feels toward her father (Paul Calderon) and the emotional abuse that led her mother to suicide. Her rage, Kusama makes clear, comes from the dominant man in her life. But watching Diana walk with her unblinking sneer through the hallways of her Brooklyn, N.Y., high school, before we know anything about her home life, we can easily see her anger as the classic outsider's resentment at kids who are smarter or prettier or more socially graceful. (That's the classic youth movie component that I think will hook male as well as female moviegoers.)

You have to hold onto Diana's anger and determination to do things her way because Kusama has saddled the character with a pretty hoary plot device. Diana's father is a macho traditionalist from whom she has to keep her boxing secret. Her brother, Tiny (Ray Santiago, playing a character whose name tells you everything you need to know about his function in the movie), has been forced into boxing by his old man, who thinks men need to know how to fight. He also ridicules Tiny's desire to go to art school as a waste of time.

There's no way a movie could be made about a young woman who enters the world of boxing and not be about the sexism she encounters there. But Kusama makes the mistake of turning her sexists into predictable pigs with dialogue like "Would it kill you to wear a skirt once in a while?" or "This equality crap has gone too far," and falling back on clichid devices about traditional media images of women. (There's a montage of TV commercials showing dewy-fresh girls or dutiful housewives.)

It's completely believable that some of the old-timers (as well as some of the young guys) at the Brooklyn gym where Diana trains would think that women have no business boxing. But there is simply no way that anyone involved in the sport -- no matter what they think about women boxing -- could not have heard the noise being made by fighters like Lucia Rijker or any of the hundreds of other women boxing as both amateurs and pros. (Certainly women boxers weren't a novelty to the men of the real Brooklyn gym featured in last year's documentary "On the Ropes.")

When "Girlfight" shines it's because Kusama simply ignores all the blab about whether women should box or not and concentrates on Diana coming to feel she belongs in the ring. Watching her hone her aggression into a boxer's skills, there's no doubt that this is what she's meant to be doing. That type of skill is its justification, the kind that makes the arguments used against it moot.

It's not hard to understand why some people are repulsed by boxing, but it's next to impossible to convince those people that the sport isn't more than two people beating each other up. Kusama's scenes of Diana's training are maybe the best demonstration of the intelligence and skill that goes into boxing that the movies have shown us. She achieves it by simply taking her time, allowing us to observe Diana's growing confidence and acumen as her trainer Hector (Jaime Tirelli in a very likable performance), the man who becomes the real father figure in her life, works to sharpen the ability he intuits in her. As Hector teaches Diana how to throw combinations, Kusama distinguishes between each type of punch so carefully that by midway through the movie she's educated us to distinguish a jab, a hook, a cross, an uppercut and how those punches work in combinations.

Each of Diana's bouts is shot differently, and Kusama and her cinematographer, Patrick Cady, use the simplest and most direct methods for allowing us to see Diana putting what she has learned to use, using an overhead camera to let us observe her footwork. Movies tend to turn boxing matches into primal/metaphysical battlegrounds, mythologizing the sport instead of elucidating it. Without doing anything fancy or denying the brutality of boxing, Kusama is alive to its visual beauty and the physical interplay between fighters in a way that is utterly unique in the movies. She's putting us inside Diana's boots, bringing us along with her as her training turns into instinct.

Kusama also surprises by avoiding the expected sentimentality of the clichis. The relationship between Diana and her father (Calderon gives a one-note performance, but he has been saddled with a one-note role) is weighted by the memory of her mother's suicide. Kusama doesn't patch things up between them after their inevitable confrontation, which is not only surprising but refreshing -- there's nothing that's more of a letdown than when a movie asks you to believe that an obvious son of a bitch is really just misunderstood. And I like the offhandedness of the scenes between Diana and Adrian (Santiago Douglas), the good-looking but not terribly bright fellow boxer she falls in love with. Their scenes are unforced, easy, the believable mating dance of two kids whose impulse to let go (emotionally as well as physically) competes with the discipline of their calling. It's a bummer that Adrian falls back on the most traditional thinking when he has to go up against Diana. (The obvious, understandable reason for objection is that she's a much better boxer.)

I wish Kusama were a better actor's director but perhaps that will come. Rodriguez was picked for the role out of an open cattle-call audition. She's undeniably striking, and when she gets to show her sleepy, sly smile, she lets you share Diana's pleasure in feeling alive and purposeful for the first time in her life. But Rodriguez hasn't received the director's help that would delineate her performance. Kusama allows Rodriguez to sneer into the camera far too much, and though she's a terrific, charismatically sullen subject, Diana's roiling, conflicted loyalties tend to remain hidden beneath her stony, resentful face. I hope her next role will take her in a different direction, perhaps even bring out the sense of sly comedy that her smile suggests. Filmmakers who see Rodriguez here must feel a little like Hector watching Diana spar and seeing her possibilities play out in their heads.

"Girlfight" is an easy movie to enjoy. I just wish it were a better one. While women boxers are struggling to achieve the same opportunities and paydays as their male counterparts, no one could argue with Kusama's assertion that sexism is hindering women who go into the sport. And while you can't deny that the attitudes of people who think women have no place in the ring contribute to those inequities, it's a shame Kusama wastes so much time on the small-time carping of men who'll never be anything but small-timers themselves. If she had made us understand that was where their objections came from, the film would have more depth. Watching Diana in action (or watching a pro like Rijker) the arguments about whether women belong in boxing blow away like so much fluff. Landing a punch, Diana is doing what she was born to do. That's the movie's real feminist triumph: an authentic nontraditional image of female beauty, one that's inseparable from strength.

Shares