Sometimes the most fascinating thing about being a spectator at the parade of movies that passes by from year to year is trying to figure out why certain movies are made when they are. Sometimes, as in the case of the aggressively offensive Nancy Meyers comedy "What Women Want," it's the only fascinating thing. For anyone who's forced to endure it -- and I pity any human creature, male or female, who's dragged to it by his or her date -- my words of advice are this: Treat it as a sociological experiment. Why is a movie like "What Women Want" slipping into the stream right now, whether or not it really is what women, or anyone else for that matter, want?

The answer is simple, and it's explained in the movie's first half-hour: Women have more buying power and more disposable income than ever before. They're a juggernaut, and somebody's test-marketing somewhere has determined that they want to see Mel Gibson dancing about like a frustrated elf as he tries to tug a pair of pantyhose over his adorable little keister. ("See how he likes it!") They want to see a willfully clueless-about-women man taken down a peg or two. They want to see him admit, "Women are smarter than men." Because maybe if he says it, then it must be true. Right?

And does my butt look big in these pants?

There's no way around the fact that although "What Women Want" is being marketed toward women, it does nothing but condescend to them. For that reason alone, it's an intriguing if ugly little nugget of social history. Gibson is Nick Marshall, a superhandsome, womanizing, divorced advertising guy who swings into his Chicago office every day with a mix of charismatic sexual savoir-faire and an inflated sense of entitlement. The women who work with (and mostly under) him both tolerate him and swoon over him, confused creatures that they are; they grumble over having to do his filing, but they fairly crumple with delight when he pays them a compliment or bumps into them accidentally.

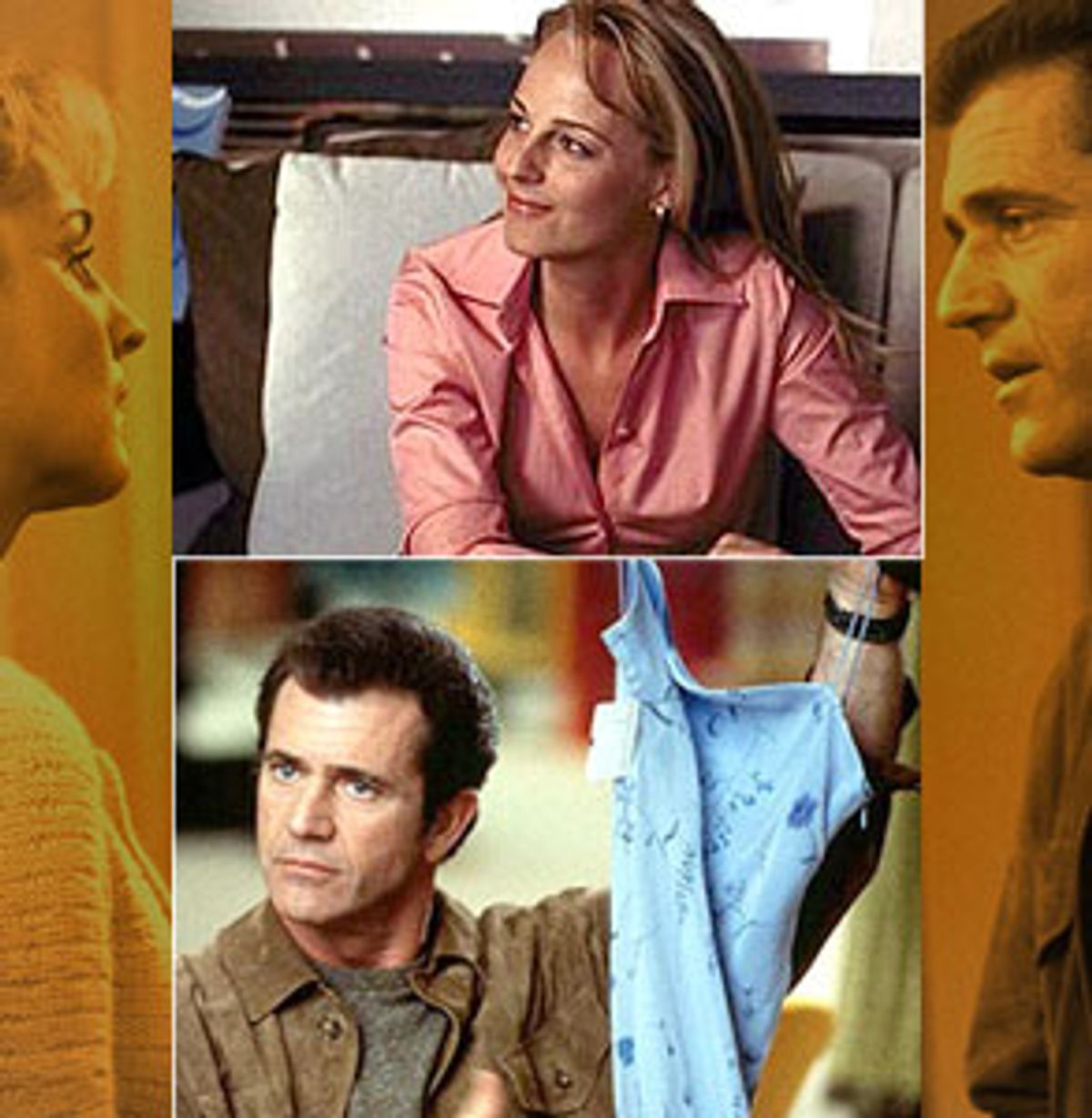

Nick's nose is put out of joint when hotshot go-getter gal Darcy Maguire (Helen Hunt) is hired away from a rival company and moves into his firm as creative director. Gibson's boss, Dan (Alan Alda, in the kind of razor-toothed nice-guy role he does better than anyone), has made it clear that, seeing as women are holding the purse strings in today's economy, his firm needs a woman's touch. (He doesn't use those exact words, but he might as well have.)

That makes Nick resent Darcy even more; when she distributes pink boxes filled with girly products (home leg-waxing kits, moisturizing lipstick, padded bras) and asks the creative team to think of new ways to sell them to women, he begins to despise her. He likes naked girls in his ads, goddamn it. Does this mean he'll actually have to change his modus operandi?

Suddenly, an accident knocks Nick unconscious. When he awakes, he realizes he can hear the thoughts of the women around him. It's mostly an unbearable cacophony of prattle about calorie counting and makeup colors, but he quickly realizes that he can use his newfound power for evil. So he sets out to sabotage his new colleague by stealing her ideas and presenting them as his own.

Predictably, he falls in love with her in the process. During this time, he also connects with his teenage daughter (Ashley Johnson), who is virtually a stranger to him, and becomes distressed and moved by hearing the thoughts of a suicidal young woman. Before long he is that most docile and desirable species of wildlife: a changed man.

That's giving away the ending of "What Women Want," but only in the barest sense, because anyone who has ever seen an ad knows how "What Women Want" will end. It's a movie draped like a pampered courtesan around that most basic of women's fantasies: the idea that a man will change for her, as the direct result of nothing more than coming into contact with her very essence.

Of course, men learn from women all the time (and vice versa), and sometimes they do change. But Meyers, aided and abetted by screenwriters Josh Goldsmith and Cathy Yuspa, isn't deft or smart enough to just give us a fanciful joy ride. Her story has to be soaked in the same woozy psychology that Oprah Winfrey indulges in. As an explanation for why Nick thinks he's the center of the universe, we're told that his mother was a Vegas showgirl and that he was raised by a gaggle of cooing, fussing, adoring, half-naked women who catered to his every whim. Of course it should follow that Nick grows up to be a guy who never listens to women and thinks of them as his servants.

Yet that's not so much useful background information as some screenwriter's conception of what women would like to believe about a character like Nick. It's more convenient to buy the idea that a man raised by showgirls would learn to view women as objects, when in reality he'd probably be the kind of guy who enjoys listening to women, pleasing them and just being around them. And he probably wouldn't leave the seat up, either.

The jokes in "What Women Want" are facile and cheap, riffing on the blandest and most tiresome stereotypes about men and women. There's one particularly pathetic joke in which Nick pretends he's gay to hose down a female admirer's feelings for him. The movie is unbecomingly catty as well. Valerie Perrine and Delta Burke are the two "yes" women who work for Nick, rushing to help him take off his coat and fetch his coffee when he gets to the office. When he first realizes he's received his special "gift," he's surrounded by feminine chatter all morning, until he reaches the inner sanctum of his office, where all he hears is what his two assistants actually say -- the not-so-subtle subtext is that they have no thoughts.

The female characters here don't provide many challenges for the actresses who play them. Marisa Tomei, an appealing and astute actress, has a thankless role here as a coffee shop worker who's smitten with Nick. And Hunt's performance is the kind of thing that will very quickly make her tiresome as an actress. Her Darcy is a sharp cookie who nevertheless hides layers of insecurity underneath, just the sort of character that women are supposed to immediately identify with.

But Meyers has no use for Hunt's whiplash comic timing here. Instead, Hunt gets plenty of opportunities to be stern and no-nonsense: She's really good at making her mouth look like a straight little blank line. Her characterization of Darcy seems like nothing more than a conceit, a ruse to fool us into thinking that maybe she's not so vulnerable, so that later we can pretend we're surprised to see that she has weaknesses.

"What Women Want" is full of those false surprises, a suggestion (if not a confirmation) of Hollywood's belief that genuine surprises are the last thing moviegoers want. It's a shame, because after his ponderous and bloated performance in the equally loathsome "The Patriot," the world could use a surprise from Gibson. I've long adored Gibson as an actor, partly because he's smart and intuitive, and partly because he's gorgeous to look at. His best performances may not be his flashiest, loudest ones. In 1997's "Conspiracy Theory," as a mentally unbalanced cabdriver who concocts and disseminates elaborate theories about government conspiracies, his performance was a small marvel, a clutch of nervous tics and twitches that he plays beautifully for laughs -- and then you realize he's turning a vulnerable and guarded character inside-out before your very eyes.

But Gibson doesn't work any magic in "What Women Want," short of turning on his crinkly smile now and then. His comic gifts are woefully underused here: If it's amusing at all to see him prancing around his bathroom in those pantyhose, it's funny only in a fleeting, predictable way.

Gibson moves beautifully, with a comic grace that's infinitely sexy, and you get a taste of that in an early scene where, bounding out of his apartment building, he tells the doorwoman he's feeling "fit as a dancing bear." The line is funny because it perfectly suits the way he's just come tripping lightly through his building's doors, like a stocky athlete with Gene Kelly in his heart. Later, when he breaks into an impromptu soft-shoe to Frank Sinatra's version of "I Won't Dance," the movie seems to skid to a stop for just a moment, taking a hard right turn into the dream world that we wish movies could be. I wanted to watch him dance forever.

But the sequence lasts barely a minute, and the rest of the time Gibson simply goes through the motions. He's an exceptionally charming comic actor, and watching him here is hardly torture. But the performance feels constrained, as if he knows he's the picture's chief marketing draw -- in essence, its dancing bear.

That's part of the air of calculation and heavily perfumed cynicism that hangs over "What Woman Want" like a poisonous cloud. If the final vision of "What Women Want" is at all grounded in reality, it's almost too depressing to think about. Women want men to listen to and understand them, and they also want men to tell them what they want to hear. It's much more cheering to think of "What Women Want" as an extended commercial for Hollywood's idea of what it thinks women want. At one point in the movie Darcy, referring to the buying power of women, admonishes her assembled advertising minions, "We can't afford not to have a piece of the $40 billion pie." Neither can the movie industry. Now it's just waiting to see if we'll bite.

Shares