"Two Can Play That Game" is the latest entry in a recent flurry of romantic comedies about affluent, successful (or at least just extremely comfortable) African-Americans rafting through the rough waters of romance. Movies like this one, or earlier pictures like "The Brothers" and "The Best Man," are of course aimed at black audiences, even though they're not solely for black audiences. And even when they're not particularly good, they're at least refreshingly vital. For one thing, scenes that take place in restaurants and other public places are often only dotted with token whites. It makes you think differently about decades' worth of restaurant scenes with that one black guy seated over in the corner behind the potted palm.

Yet these movies aren't exclusionary. Their chief vernacular is the language of romance and its vagaries, and it cuts a sharp if zig-zagging swath across class and race boundaries. "Two Can Play That Game" doesn't zip along as smoothly as it should. It bogs down somewhere in the last half, partly because it's based on one woman's 10-day plan to cement her relationship with her man, and 10 days is maybe a few too many. Couldn't she maybe fast-forward through a few of them?

But even though "Two Can Play" -- written and directed by Mark Brown, who wrote the screenplay for "How to Be a Player" -- seems at first designed to be a simple women's revenge movie, it ends up charting a bumpier and more interesting road. Shanté Smith (Vivica A. Fox) is a glamorously successful advertising executive -- strutting about in her high-rise high heels, she's as sleek and polished as the floor-to-ceiling windows in her swanky office. Her girlfriends (played vivaciously by Mo'nique, Wendy Raquel Robinson and Tamala Jones) look to her as the last word in male-female relationships, and you can see why: This perky Ms. Fixit is so pulled together that she seems able to control men's minds with a flip of her gorgeously straightened hair.

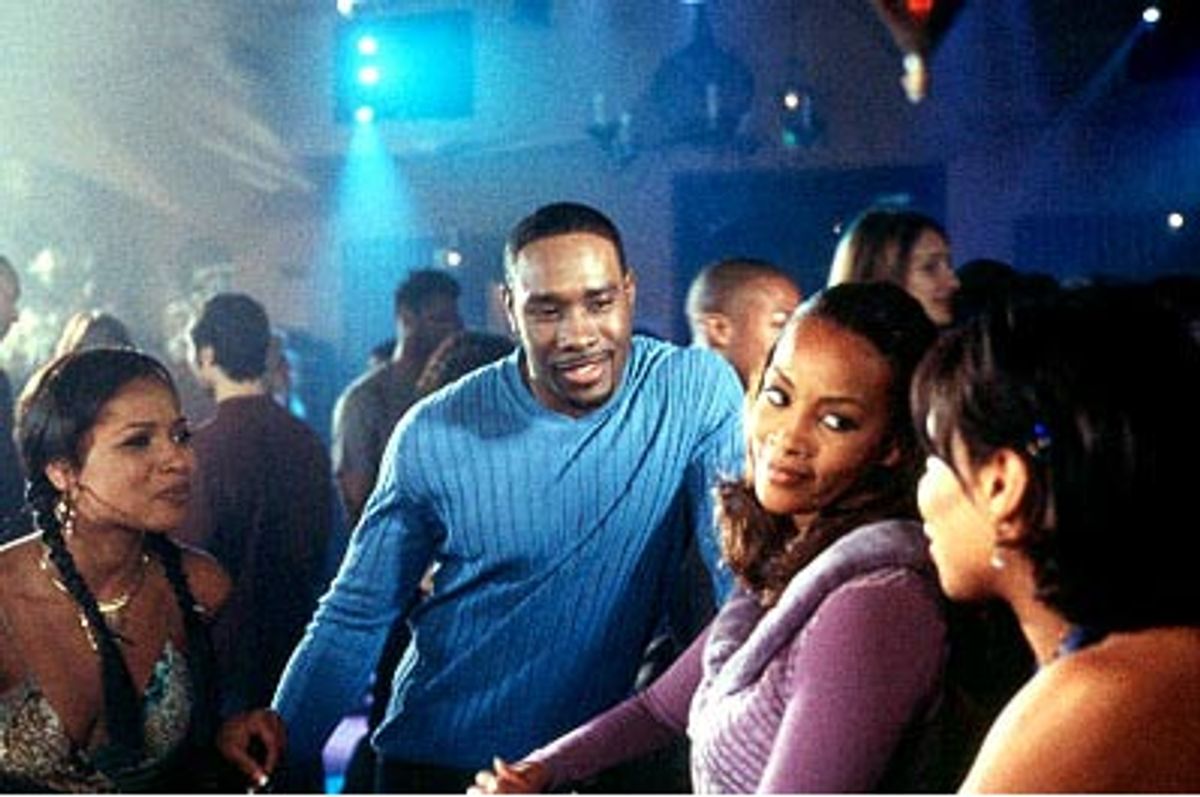

But when she catches her equally dashing and successful beau Keith (Morris Chestnut) at a club with another woman, she knows it's time to take action. She enacts her 10-day plan, addressing the camera directly to explain it to us step-by-step, which starts with calmly and gently initiating a breakup, ostensibly in order to give both partners some breathing room. The rest of the plan is a convoluted minuet-boogie involving allowing his plaintive phone calls to go unanswered; showing up at his house unannounced (wearing a killer outfit, natch) to drop off some of the stuff he's left at your apartment; and making sure he sees you with another guy who's even more handsome and successful-looking than he is. "If you want him back, punish him," Shanté admonishes us with an unnervingly icy glare.

"Two Can Play That Game" is ruthless at first, almost to the point of being unlikable. And early on, it tangos with some distressingly retrograde sexual politics: Shanté informs one of her girlfriends that in order to keep her man, she needs to learn about sports and take cooking lessons. (Never mind that the friend is a top exec at a big engineering firm.) And at first Shanté is overly eager to blame her man's perceived infidelity on another woman, as if his dick were attached helplessly to marionette strings.

But the tables get turned around so much that the picture almost manages to make sense of the convoluted games men and women play with one another -- as much sense as they can ever make, that is. For advice on his love troubles, Keith turns to his pal Tony (Anthony Anderson), who quickly realizes that Shanté is a pro at the love game. Rotund and robust, he's crudely hilarious in advising Keith how to counteract Shanté's wicked spell. You can't help cackling at him when, trying to interest Keith in another babe, he makes googly-eyed comments about her "nice big old breastusses!"

Part of the reason that absurd joke is so funny is that it flies in the face of Shanté's sophistication: It's the kind of thing men might say around one another, but in front of women, it just exposes them for the doofuses they are. But the men aren't always the butt of the joke in "Two Can Play That Game"; Keith gets his own back at Shanté, and her smugness, which gets a little wearying as Fox plays it, eventually gives way to more complicated feelings. No matter how much you sympathize with the women, "Two Can Play That Game" doesn't just park its butt in the tired old sisterhood groove. And there's something freeing and fun about seeing a woman as put-together as Vivica A. Fox howling at her girlfriends' jokes about big penises and no-good men: She's not so snooty that she won't let herself be one of the girls.

In a perfect world, black Americans wouldn't need their own romantic comedies. But in this world, at least now, I think they do, if only because most "white" romantic comedies these days are so embarrassingly square. "Two Can Play That Game" ultimately feels somewhat overprocessed, and its humor is a little too broad at times -- it probably crosses the acceptable threshold of penis and boob jokes, whatever that is. But as Diana Vreeland once said, bad taste is better than no taste. At least "Two Can Play That Game" has some wriggle in it.

Shares