According to the official wisdom of the moment, sweetness and optimism is all we want from art or entertainment right now (and the official wisdom isn't interested in the distinction between art and entertainment, if any can still be said to exist). So "Hearts in Atlantis" seems, at first anyway, to arrive right on schedule. Yes, it's based on a Stephen King story, but in this instance King's haunted imagination has apparently been dipped in honey and left outside to harden on a cool autumn afternoon.

Like all of King's work, this tale of an impressionable boy's friendship with a mysterious transient has ominous undertones, but the resulting film directed by Scott Hicks is afflicted by terminal nostalgic drift. You come out of the theater with nothing more specific than half-pleasant memories of baseball gloves, Ferris wheels and vintage automobiles. I've had naps that were more exciting.

In his brief but strikingly successful filmmaking career, Hicks has become a master of a distinctive middlebrow style that combines the slowness and attention to pictorial detail of old-fashioned art cinema with the ebbing and flowing emotional manipulation of a Hollywood soundtrack. (One friend of mine got up and walked out of Hicks' "Shine" after the long traveling shot that opens the film.) Add weeping violins and sprightly woodwinds to Yasujiro Ozu 's "Tokyo Story" or Robert Bresson's "Mouchette," so the audience knows what to think and feel at every moment, and you get Hicks.

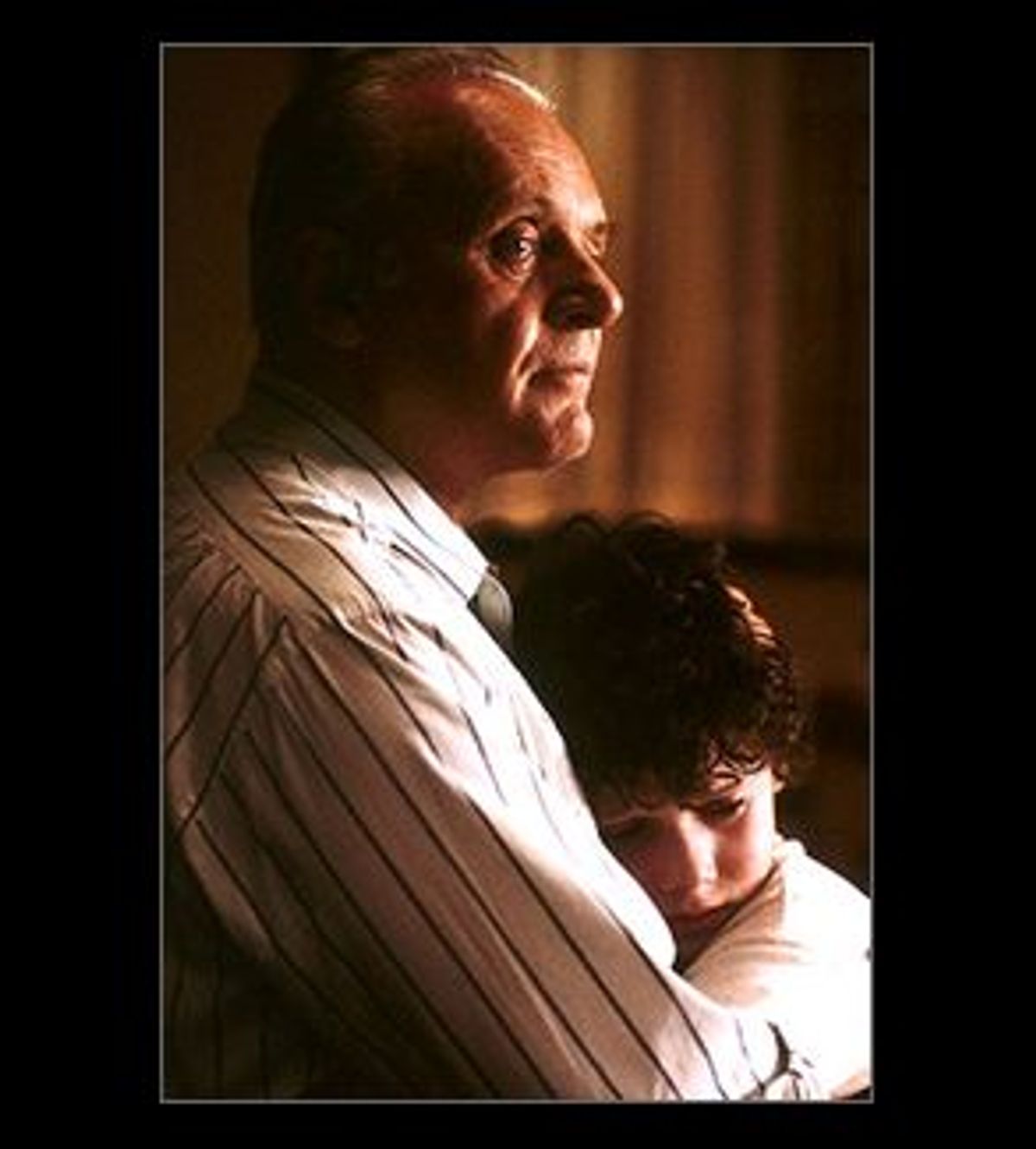

On one hand, Hicks is capable of locating extraordinary beauty in the none-too-thriving Connecticut town where 11-year-old Bobby (played by a curly-locked youngster named Anton Yelchin), in 1960, meets a peculiar new neighbor named Ted Brautigan (Anthony Hopkins). On the other hand, Hicks seems more interested in his images -- a girl hanging sheets on a clothesline in pale sunshine, a Schwinn Black Phantom bike gleaming in a toy-store window -- than in drawing sense or meaning from King's ambiguous tale (by way of William Goldman's screenplay).

In "Shine" and "Snow Falling on Cedars," Hicks' previous mainstream features, one could argue that this tendency didn't matter, because those films were more about picture and sound, waves of inarticulate emotion, than narrative as such. But as much as King's work may depend on nostalgia and the wayward paths of childhood imagination he remains a storyteller at heart. As much as Hicks labors to capture the flavor and texture of Bobby's ordinary world as it is suddenly transfigured, this movie has none of King's inexorable forward momentum.

This film is adapted from only one story in the book "Hearts in Atlantis," a bittersweet portrait of American life before and during the Vietnam era. The book is a brave if not altogether successful experiment, but removing the tale of Bobby and Ted from its larger context -- a society whose anxieties and instabilities are starting to bubble to the surface in unpredictable ways -- makes it seem more whimsical than disturbing. The question of whether Ted is a crazy old lecher or a psychic genius being pursued by nefarious agents of who-knows-what never seems either puzzling or especially important.

As in several of King's tales of childhood, most notably the classic horror novel "It," we begin in the present, when an all-grown-up Bobby (David Morse) receives a Fed Ex package containing an ancient baseball mitt. This is of course a talisman, a summons from the past, and Bobby follows it back to his Connecticut hometown for the funeral of Sully, his boyhood best friend, and backward to the strange (if, in this version, rather sleepy-strange) events of 1960.

In terms of King-derived films, we're somewhere between "Stand by Me" and "Carrie." Bobby is one of those half-innocent, half-knowing kids King specializes in, who is beginning to grasp that the good and the righteous do not tend to triumph in life, but is sticking to his guns anyway. He lives with his widowed mom Elizabeth (Hope Davis), who natters on constantly about what a louse and deadbeat Bobby's now-deceased father was. One of the most depressing facts about "Hearts in Atlantis" is that its nitwit dialogue, so redolent of screenplay software, is attributed to Goldman, who is still regarded by many as a prince among Hollywood writers:

Mom: Your father never met an inside straight he didn't like.

Bobby: What's an inside straight?

Mom: Never you mind, Bobby-O. Don't you ever let me catch you playing cards for money.

You get only one guess about what happens when Bobby gets the chance, a few scenes later, to win some money in a card game.

Davis is a still-young actress who has been predicted for stardom several times over, but it's safe to say that this uneasy, shrewish role won't exactly turn her into Marilyn Monroe. She has the right face for the purposeful and determined Elizabeth; Davis' nose, chin and body language are those of an arrow springing toward its target. (Although this film is devoid of any nudity or explicit sexuality, there is one shot of Davis backlit in a sundress that makes it clear she doesn't resemble any of the moms of my suburban upbringing.) The real problem is that this is another of King's awkwardly managed female characters, a wronged and injured woman who is also selfish and small-minded.

Compared to her, Ted, the doleful upstairs neighbor who arrives with his belongings in paper bags and mismatched suitcases (to Elizabeth's grave displeasure) seems like a veritable Samuel Johnson. It's surely no accident that his name combines those of poet Ted Berrigan and novelist Richard Brautigan, two offbeat literary heroes of the '60s whose work King almost certainly knows. Ted quotes Elizabethan poetry and dispatches Bobby to the library to read "Lost Horizon" and "A Tale of Two Cities." He also has a tendency to slip into trance states without warning, and insists that "low men" in anonymous clothes and anonymous cars are after him because of "a certain something I happen to have."

Ted also portentously informs Bobby that the boy is going to kiss his angelic, tomboyish pal Carol (Mika Boorem) and that this will be the kiss in his life "by which all others will be found wanting." (It happens, so help me, on a stalled Ferris wheel at the fair.) Hopkins is of course one of the finest film actors of this era or any other, and he is able to seem mournful and profound drifting around this dismal neighborhood in baggy vintage attire, serving as low-wattage fairy godfather to Bobby, Carol and their friend Sully (who never plays much of a role in the story).

Things happen, in Hicks' supremely undramatic, watching-paint-dry fashion: A neighborhood bully tries to molest Carol, the "low men" seem not to be imaginary after all, Bobby's mother's behavior ranges from the stupid to the inexcusable. But the story's sinister undercurrents all slip away into nothing and as we return to the adult Bobby, the whole project seems bathed in a bland wash of nostalgia, which as usual has more to do with forgetting than remembering. Then again, I can't blame anyone for wanting to spend two calm and pleasant hours in the dark forgetting things, and 8 or 9 or 10 bucks for Anthony Hopkins to be your meditation group leader is, on balance, a pretty good deal.

Shares