I own a necklace made from the teeth of mules, or maybe antelopes. I don't know why I would think they are from antelopes, except that they are long and flat and kind of yellowed, which is how I imagine antelope teeth look. Someday I will have a display case for them, but for now they hang on the wall of the bathroom, a curiosity for guests to look over while they attend to other business. The teeth are suspended from a blue cotton twist of yarn, fanning out over a two-foot-long breastplate fit for a warrior.

My husband wants to wear them for Halloween every year, but I never let him. I got them from a Native American, so somehow they seem better than Halloween. They need a display case.

I also keep the skull of a bull -- a great, white, sun-bleached thing with foot-long horns the color of dry hay. I kept it on the wall for a long time, but now I keep it hidden high on top of a bookcase, where I think to look on it only once or twice a year.

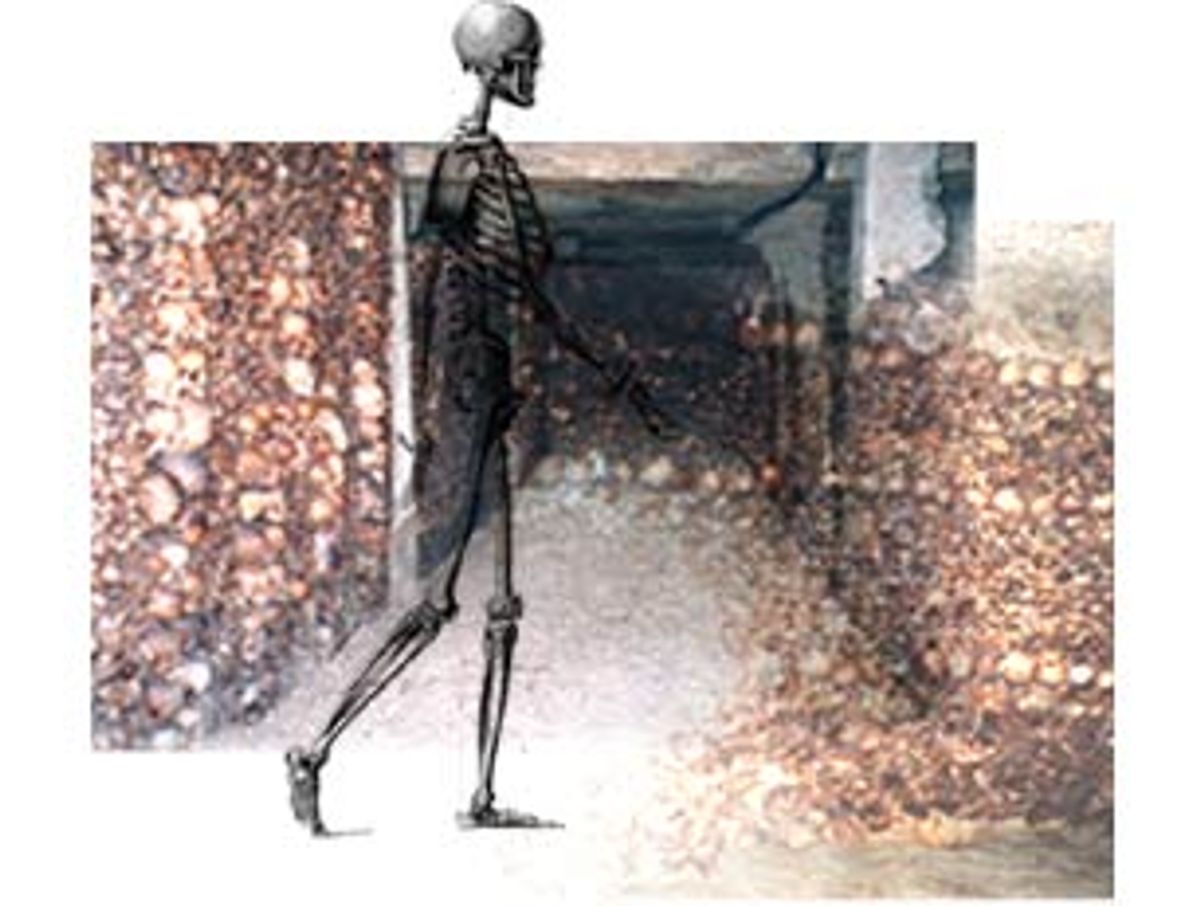

I have seen more bones than most people will in a lifetime. I have looked on the skeletons of thousands of people, some put up like wallpaper, some assembled as furniture, others poking from the deteriorating ends of mummies, and still more displayed bare and unadorned, except for their simple gossamer coats spurned by long-dead spiders.

I am especially drawn to displays of bones -- grand, magnificent displays that artists have erected in the chapels and ossuaries that adorn Europe like bright baubles for the religious and the curious alike. Until a few years ago, I didn't even know that these showcases, these "bone chapels," existed. Now I hunt these European oddities with a relish that startles even my liberal-minded friends. And though I have now seen more skeletons than perhaps anyone should, each time I successfully track down a new display, I find myself completely captivated, completely enamored, as if it were my first time.

Eight years ago, I boarded a jet for Europe. I wanted to take it all in, to soak in the culture that for so long I had only imagined from my side of the Atlantic. Together, my husband and I walked the streets, traveled the trains, spent hours absorbed in Notre-Dame, slipped and slid down a glacier in Interlocken, were trapped long past dark in the mummified remains of Pompeii before the Italian security guards snatched us out.

Pompeii. Now that I look back, maybe that is where my fascination with bones began to form, to coalesce from the dirt and ash and pumice that littered the ancient streets. In Pompeii, those who were trapped when the volcano erupted, who couldn't or didn't leave, were coated so completely with powdery white ash that their bodies permanently froze into their last contortions before death. These figures are displayed today in clear coffin-like boxes, where one can see the ash-coated mother defiantly protecting her ash-coated child, the slave curled in agony as the ash suffocated his lungs.

These few bodies left behind are emblematic of the city itself. Like them, the city is similarly entombed. Pompeii is a dead city, a mummified city, a relic. All that's left of the thriving commerce and busy citizenry are the skeletal remains of houses. To crouch alone in the cobbled streets in the damp, dark evening air is to feel the weight of its lassitude surround and penetrate you. It is a quiet city, an empty city -- a city of death.

After Pompeii, I began searching out more such oases of death, propelled by a morbid curiosity and some small, gentle push from something else unnamable in my mind. I searched, too, for that feeling of being held in a cradle of such utter lifelessness, of otherworldliness, that Pompeii had evoked. I found it in the bone chapels.

In Rome, the sky was a muted gray, the façades of buildings rain-washed and damp. My husband and I had arrived at the Cemetery of the Capuchins, what promised to be an above-ground crypt tended by Capuchin monks. I had expected to see an interesting variant of mausoleum or graveyard -- perhaps an indoor graveyard, with plastic Astroturf and dusty silk flowers.

We were standing outside the monastery doors, in the misting rain, because of a little anecdote my husband had shared the day before about the origin of the word "cappuccino" (as in, "I'll have a grande cappuccino, low-fat milk, please"). We had stood together over espressos in a tiny cafi as he told me that Capuchin monks shave a neat bald circle in the exact center of their hair, and that Italian locals have long joked that the result -- a ring of dark hair framing a white shaved spot of skin -- looks uncannily like foamy white milk encircled by the brown stain of espresso. Hence the word cappuccino.

"I'm not falling for it," I said. "You're joking." He's been known to tell tall tales before.

"I'm not," he insisted, and that is how we found ourselves huddled against the wet walls of the Capuchin monastery the next morning, waiting to be let in. Eventually, a monk in a brown wool frock (tied with a rope -- a real rope!) met us at the door, and I was chagrined to find that his hair did in fact look amazingly like the cappuccinos we had enjoyed at yesterday's cafe.

With a stiff wave, the monk solemnly directed us into a winding stairwell topped by a darkened passage. We emerged into a tiny room painted sky blue. I sucked in my breath as I took in the sight before me. Bones -- a panoramic display of bones had been positioned in flat, elaborate patterns adorning the walls, floor and ceiling. The yellow-brown scapulae and vertebrae, fibulae and tibiae, arranged so artfully against the blue plaster, reminded me of old, yellowing lace held up against the sky.

A worn velvet rope forced us into single file, our backs against a wall, the rope the only thing separating us from the sight ahead of and above us. Against two walls, shelves had been erected to hold the skeletal, decomposing remains of monks dressed in their frocks, appearing to rest at ease, clutching wooden crosses as tough, aged flesh dangled from withered fingers. On the floor, dirt mounds imitated graves, but the occupants were surely not buried. Instead, they had been disassembled and their skeletons scattered and arranged among the rest, disappearing anonymously into the design that crept over this elaborate spectacle.

And the design was paramount. It covered everything, every surface, creating spiral and angular shapes, patterns reminiscent of flowers and paisleys, an artist's doodle pad. Even the hallway's hanging chandeliers had been made from the more delicate bones of the human form. I felt as if I were being cradled in a womb of death, with the swirling walls, floor and ceiling forcing the spectacle of my own mortality into my face, a veritable rounded crystal ball of bones with myself as the future in its center.

Each of the tight, adjoining and highly decorated rooms led to another, finally landing us in a chamber with the most grisly motif of all. No longer abstract, the patterns instead reflected haunting images of mortality meant to be stamped in the unwary tourist's mind. Upon the ceiling, replicated in meticulous detail, was a carefully crafted figure of the Grim Reaper: His bone face was a human skull, and the blade of his scythe was composed of an elegantly descending column of coccyges that tapered realistically into a sharpened edge. Near him, the visage of an ancient clock with Roman numerals, completely formed of bones, symbolically ticked away man's time.

I emerged from the Capuchin cemetery shaken, horrified, but gripped with even greater curiosity. Were there other places like this, I wondered, or had I stumbled into a singular anomaly? Perhaps the Capuchins, I theorized, with their emphases on poverty and austerity, had at one time found burial wasteful and expensive. Perhaps a lunatic monk had created this site in a fit of manic inspiration, and now the brothers felt obliged to tend this sacred cow rather than dismantle it. Perhaps there was something about Catholicism that I just didn't know. Perhaps it was explained in a book somewhere, but then again, perhaps it was simply up to me to make my own meaning, as I had already done.

I often ponder what it is about bones that lures me so, because when I look into my fascination with them, what I see at its heart is really a fascination with death and its accoutrements -- the picturesque graveyard, the elegant mausoleum, even the bone chapels. I know I'm not alone in this fascination; many people share it on some level. Why else would so many people be stirred to walk through old cemeteries, to read the headstones? Why do we, as a society, keep our dead so near us in cement slabs and boxes, in crypts and sepulchers, or even disassembled into designs?

The neat explanation is that graves and their brethren serve not only as the loci for our grief, but as places of pilgrimage where loved ones symbolically still live on. To visit a grave, neatly trimmed and hedged, is to visit a memory that will likewise eventually codify into a neat, delineated image.

But many people walk graveyards where the occupants are all strangers. People walk graveyards because they feel a tingle of some restless emotion snake through them when they look at rows of marble and granite headstones. They feel a presence -- or is it a pressure? -- that is vaguely titillating and vaguely horrifying at the same time.

Bone chapels and their ilk push this feeling further, for they are not merely memorials to the dead, but memorials to death itself -- to its awesome complexity, to its simple absurdity. And therein lies the difference between looking at a grave and staring at the eyeless holes in a human skull that adorns a candle-lit wall. A human skull, full of rot and the dry husks of larvae, is a challenge. It is a mystery. A skull represents the inner shadow of a deceased person's face, the pale ghost of his mind reaching out through the now-empty eye sockets. It offers no solace. It commands respect. And above all, it opens conversation.

With a little searching, I discovered that many bone chapels, particularly those in Eastern Europe, were built as reminders of the terrible plagues that were the scourge of old Catholic European cities, which as it turned out was the basis for the Capuchins' creation. One of the most spectacular is the Ausona-Hallstatt Chapel near Prague, where the bones of 20,000 plague victims have been arranged on the walls and ceilings, culminating in a grand bone chandelier to commemorate those who died. (Or perhaps to remind the living of the tenuousness of life.)

After Rome, not yet knowing of the Austrian chapel, my husband and I traveled to Portugal. There, in Evora, a crumbling mountain town where buildings are made of stone and mortar and the streets are paved with lumpy, broken bricks and cobbles, the townsmen still congregate in the late afternoon around the central fountain, smoking and chatting. Men wear suspenders and cloth hats, and widows, leaning out from their balconies, dress completely in black.

I had heard that the town kept a chapel of bones that was more than 200 years old, the "Dos Ossos" Chapel in the church of Sao Francisco. More magnificent in stature than the Capuchin cemetery, but lacking in the Capuchin's detailed artistic nuances, it houses the bones of more than 5,000 people, which have similarly been carefully arranged into intricate patterns along the walls. Disintegrating femurs form archways, and cobwebbed skulls are stacked one atop the other to reach the ceiling in a chilling display of imagination.

The ceilings themselves are frescoed with brilliant, painted designs, and statues of saints adorn alcoves flickering with votive candles. In the central chamber, still decomposing corpses of a man and a child hang from a literal wall of bones. According to local legend, a dying wife and mother, cursing the husband and child whose ill tempers and ingratitude led her to an early death, vowed that when they died, their flesh would never rot. Both the husband and child died thereafter, and though their bodies have clearly decayed, their bones have remained on view to this day.

This chapel, too, was built by a monk, a Franciscan, who it seemed also held death high in his mind. A motto, boldly painted at the entrance, reads, "We bones lie here waiting for yours." And they do; that is the incontrovertible fact of it. These chapels use bones -- our own living remains -- as brutal reminders that life and death are smiling twins, each dancing with the other. And we, too, dance with one, then the other.

Smaller bone chapels dot the Portuguese landscape, especially in the Algarve region in southern Portugal, where you can stumble unexpectedly on them behind small-town churches. In the hot Portuguese summer, my husband and I found ourselves taking a rest from the luxurious beaches in Faro to walk the streets and window-shop.

Faro, a tourist-friendly town favored by French and English vacationers, is awash with cobbled and mosaiced streets, outdoor cafis marked by a myriad of colorful striped umbrellas, and the edge of the crystalline blue sea, where the Mediterranean meets the Atlantic in a jolly jostling of waves. Amid all the tourist glitter lies an unprepossessing 18th century Carmelite church. A small bank of steps leads to the square, three-story whitewashed building. And there, after wandering past worm-eaten confessionals and well-worn pews, I found myself once again unexpectedly stepping into that eerie European otherworld, the bone chapel.

Set behind the church proper, past an unkempt garden overgrown with weeds and tall fescue, the tiny chapel stands rigid and white in the dappled sunlight. Like a variation on a theme, instead of merely having walls lined with bones, this chapel has actually been built from bones -- from the ground up -- with nothing but bones and a little cement.

Small and spare, this chapel, while more crudely shaped than the others, impresses by the very fact that these bones have withstood the outdoor elements so well for so long -- several hundred years. On the day we visited, a young man was at the top of a tall ladder, meticulously repositioning a skull into the niche from which it had fallen. Bits of flaking bone and rot fell from the ceiling where he worked, catching in our hair as we ducked past.

As I stood under this canopy of grinning skulls, I wondered: Would their original owners be pleased with their remarkable longevity, their strange kind of ... immortality? Did these people ever think that one day their leering skulls would be gazed on by so many eyes, touched by so many hands? That their collarbones and tibia would be disconnected from their bodies, their carpi and tarpi scattered so casually with those of friends, neighbors, enemies?

After a long moment, my husband stated that when he passes on he wants his bones bronzed and reassembled and put by the door. He wants to know who's coming and going, he said. Like the skulls above us, he wants his bones to look on the unfolding generations who cross his door.

I imagined his grinning jaw hanging open to greet guests and I told him I didn't think that was a good idea. I told him he should be cremated. He reminded me of my departed uncle whose ashes were kept in an urn on the mantle. The urn fell, the ashes spilled and my aunt found that the only way to get them back together again (à la Humpty Dumpty) was to turn the vacuum on them.

"So ignoble," my husband stated. "And who will keep your ashes in their condo 20 years from now?" he asked. "Our children? And our great-grandchildren, will they carefully dust the collection of urns that sit next to the odd mules'-teeth curiosity they inherited with the china cabinet? Or will our ashes go the way of old photos that end up in antique stores, a dollar apiece for someone's smiling relative?"

"We will put them in a vault," I said. "We will scatter them in the wind. We will disappear."

As I continued to travel, I began hearing a familiar refrain: "Have you been to the Catacombs in France? Ohh! You will love them."

It wasn't until my fourth trip over that I finally found my way to the earthen tunnels that root under Paris, originating under the well-known Cemetery of the Innocents. I almost wish I hadn't.

Less elegant by far than their counterparts in Italy and Portugal, but impressive for sheer size, the Catacombs in Paris are really only a close cousin of the bone chapels, since they are not at all connected with a church or monastery. Still, they share a striking commonality with their cousins across Europe: It took artists with a disturbing taste of medium to erect them. As with the bone chapels, the skeletons within have all been broken apart and then carefully arranged into macabre designs, though these designs are not tidily kept but instead meander through winding tunnels beneath the city itself.

Technically, of course, the Catacombs are distinct underground ossuaries that utilized existing tunnels beneath the Parisian streets. Between 1786 and 1787, corpses were unearthed on a massive scale from the overflowing Cemetery of the Innocents, where sunken and often open graves had become a source of rank odor and pestilence. Instead of relocating the cemetery to the countryside, the Parisians decided to simply put the corpses under the city itself. Between three and six million Parisian skeletons were brought to the Catacombs for safekeeping.

When I finally stopped by on a wet December afternoon, there were perhaps a total of two dozen people fanned out in the winding, miles-long underground labyrinth -- so few, in fact, that my husband and I seemed totally alone in the dripping tunnels.

The air inside the Catacombs, which lie deep under the city and are arrived at only after a long, long, descending walk, is chilly and curiously without odor. Low-hanging light bulbs flicker and wane from the packed dirt ceilings, creating sharp, shadowed corners and cupolas. On each side of the narrow pathway, walls of bones tower, reaching from the floor to the wet, dripping earthen ceiling. Mounds of jumbled, cobwebbed bones are piled in pitch-black tunnels that break away from the main passageways, blocked by rusty iron grills. Corridor walls resemble dirty frosted birthday cake with each layer of bones separated by a thin jam of skulls. Bones shaped into hearts, diamonds, spades and strange hieroglyphics like alien writing flicker in the shadows. The muffled sound of muddy gravel crunching beneath my feet was often the only sound I heard in that muted sepulcher.

More than once, I stopped to find my heart beating in my ears. And for the first time since embarking on my dark odyssey, I can honestly say that I felt true, niggling spikes of fear vibrate through my body -- what I was suddenly aware of as my living body. I fought the urge to speed up our walk, which began to feel interminable.

As we hurried along, I wondered, How did I think I'd feel with three to six million skeletons surrounding me, a mile under the earth? I was walking in a literal graveyard, not only completely surrounded by bones, as I had been before without difficulty, but trapped under the belly of the earth itself, seemingly buried in with them. I began to rethink the merits of my grim curiosity, this search for that elusive, "come-hither" revulsion evoked by being so close to human remains.

Even now, I can still recall how it feels to have such a mass of ivory skulls all staring down at me. Their empty glances beat on my back, each seeming to pose the same unanswerable question. In place of eyes were thousands of black holes, hollow pits sinking far back into the skulls, where once the brains and souls of people were cradled. I remember thinking, Who knew what lay in that empty darkness now?

I began to create stories in my mind to keep them at a safe distance. This skull, I thought, belonged to a woman who died in childbirth. And he, I thought, died from syphilis. This little skull here -- this young man fell and cracked his brain open, which I can see from the proud welt arcing across his forehead. I continued in this vein until the narrow tunnel once again began slanting up, ending in the blessed daylight.

I laughed when I exited, relieved, as if a weight had been lifted from my chest, though a new burden, of a different nature, now weighed on my spirit -- or at least colored it with a bright new hue of understanding. It was as if I had looked death in the eye and found just what I had been expecting all along: mystery, terror and respect.

I remember looking up at the gray, cloudy sky, then down at my feet, where I discovered a fine splash of white powder speckling my shoes and legs. With horror I realized that it was calcium, leached from the still-decomposing bones, which I had kicked up as I walked.

Decay, I realized, is ever unfinished in these preserved houses of the dead.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

I have a fascination with bones, yes, but more so with the kind of society that can display them so generously in such grand feasts for the eyes. Sometimes I wonder why we Americans seem to have lost our taste for death. Why do we shirk the pageantry that once captivated our forefathers? Our churches hold no bones. We create no provoking displays. We keep no mummies, we burn no offerings. Instead we celebrate Halloween, a cheap pageant for children honeycombed with candy and costumes, while our southern neighbors in Mexico sit up with their dead in graveyards through the long hours of Dia de los Meurtos (Day of the Dead).

Our dead keep to themselves and we go about busy with life. We try not to think about death at all, really, except as a painful tragedy to be gotten through. We love the seasons, we say, yet we routinely ignore the seasons of the soul. We overlook the seasons of life itself.

To us, death is a personal tragedy, an obstacle we haven't learned how to avoid quite yet, though we feel (in our bones) that that too is on the horizon. I hesitate to say that our respect for death is diminished, but the truthfulness of death is routinely withheld in our culture. We watch murders on television for entertainment; we offhandedly arm our fellow citizens with handguns and other weapons of death. And while we mourn with the same intensity and complexity as others, we have even deconstructed the whole grieving process into antiseptic, defined parts that must be methodically moved through.

What we do not do is think about death in the same way that it seems some Europeans have. We never remind ourselves of its existence, either by ritual or by erecting monuments to its power, either as bone chapels or ossuaries, and we certainly (thankfully) have nothing comparable to Pompeii.

Our churches, by and large, focus on life and redemption, which is not a bad thing. But after we have achieved both those noble goals, death seems merely a small hurdle that, once past, is no longer an object of curiosity that holds any power or mystery at all. We do not know that by holding a polished human skull in our fingers, our understanding of life is magnified, and our ability to cherish it improved.

Monuments always act as sober reminders of those things we feel are too important to be forgotten, which is why we erect them. Yet we have no monuments to death, to the one profundity we all experience, without exception. So, I ask, what have we forgotten?

Shares