To paraphrase Johnny Rotten: Ever get the feeling you've been milked? More specifically, Nick Cassavetes' "John Q." leaves you feeling as if you've been alternately milked and bitch-slapped. Its manipulation is so clumsy and obvious -- and, ultimately, it goes so far astray from its original guiding principles -- that it leaves you feeling dangled and dazed. Although "John Q." is ostensibly about a young boy who is metaphorically held hostage by the shamefully inadequate healthcare system in this country, he ends up becoming a hostage to the movie itself: Director Cassavetes sets so much action spinning around the boy that we almost forget he exists.

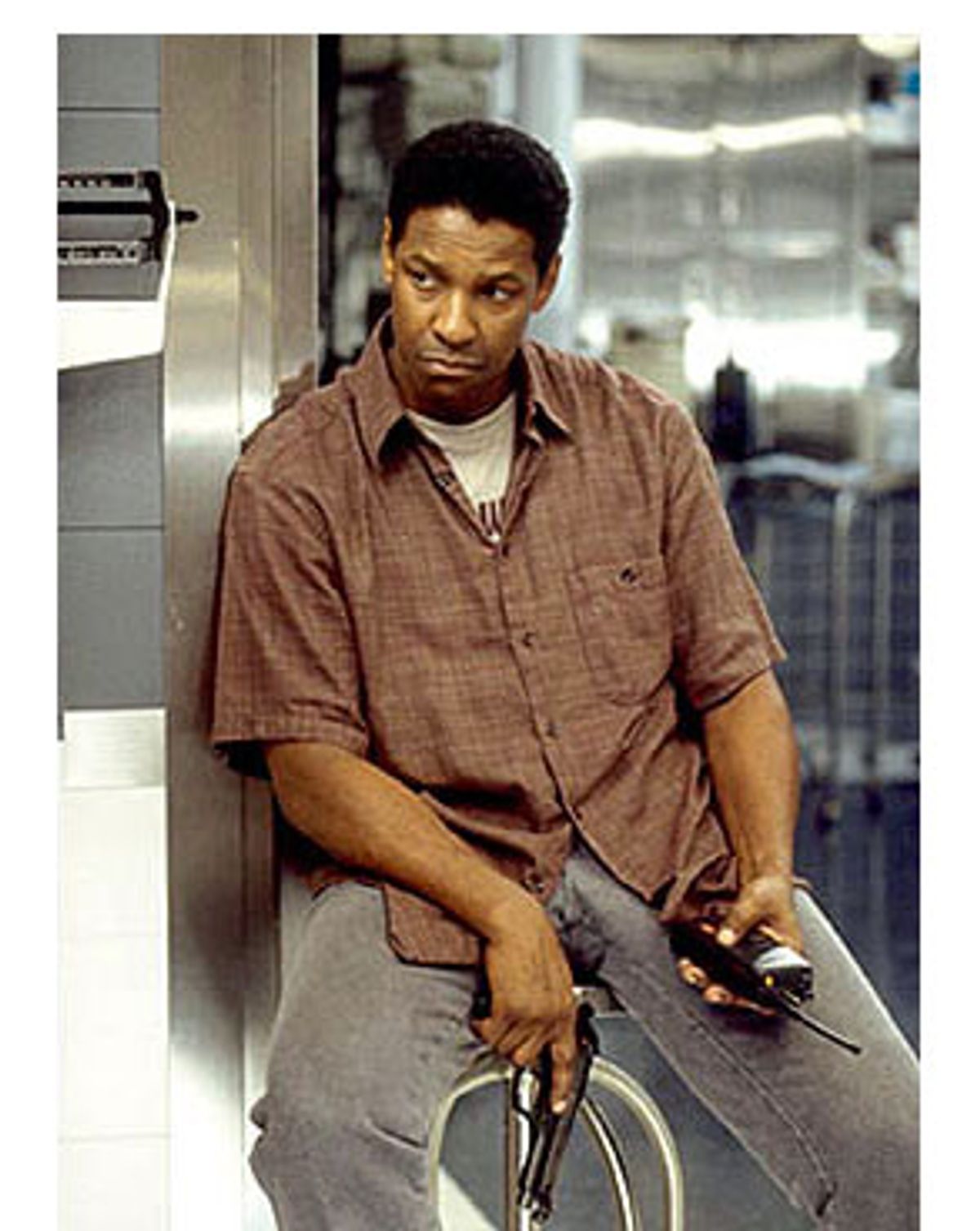

There's a good social drama to be made from the premise of "John Q." -- this just isn't it. Denzel Washington plays John Q. Archibald, a hardworking factory employee who suddenly learns that his young son Michael (Daniel E. Smith) has a serious heart problem and will die unless he gets an exorbitantly expensive transplant. John Q.'s health insurance won't cover it, and the hospital administrator he and his wife, Denise (Kimberly Elise), are forced to deal with (Anne Heche) refuses to put Michael on the transplant-candidate list until the family can fork over a massive deposit.

John Q. and Denise scramble to find the money, filling out reams of paperwork and hotfooting it over to various agencies (where they stand in endless lines as their son lies in the hospital fighting for his life). Their church raises funds for them and their friends hand over as much of their own tips and wages as they can spare. But neither the hospital nor the arrogant heart surgeon, Dr. Turner (James Woods), is interested in the measly $6,000 John Q. scrapes together. The hospital declares its intent to release Michael, basically leaving him to die.

Desperate, John Q. seizes the hospital's emergency room, locks it down and takes Dr. Turner and a handful of workers and patients hostage. Until that point, the movie's worst sin is the crude obviousness with which it tweaks and tugs at us: We see Michael collapsing on a baseball field in slow motion, his eyes slowly rolling back in his head. Later, Heche, like Cruella DeVil in a pastel sweater set, gets crisp, efficient lines like, "Your son may not live much longer. You might want to make it a happy time," and also utters words to the effect of "People get sick and sometimes they die. That's life."

But once John Q. takes over that emergency room, the movie begins to disintegrate into something more offensive than an old-fashioned socialist tear-jerker. As if Cassavetes suddenly realized that social issues are kind of, well, boring, "John Q." becomes a flashy desperado of a movie, replete with guns, violent scuffles, hostage negotiations and one extremely tense, hyperbolically overplayed moment of melodramatic self-sacrifice.

All the while, Cassavetes and writer James Kearns take great pains to remind us that they're really dealing with big social issues here: We get hardworking regular folk addressing TV cameras with heartfelt wisdom, then, as if on cue, shuffling their feet and muttering, "But what do I know? I'm just a factory worker." Shortly after John Q. takes over the emergency room, he answers a ringing telephone and when the frantic, tearful caller asks him for directions to the hospital (she has to rush her son there), he tells her the hospital is closed for repairs. At heart a decent guy, he relents and helps her figure out the route.

But the fact that John Q. is willing to endanger other people's lives (and he endangers plenty before the movie is over, although, miraculously, there are no casualties) is repeatedly glossed over and excused. Instead, onlookers gathered outside the hospital cheer him on as a folk hero; when he does release a few hostages, they rush out as if they'd just been sprung from Disneyland, gushing to police about that great guy they just met, John Q. Appleseed, who's merely finding alternative ways to spread his good sense and common decency throughout the land.

Somewhere in that tangle of high drama dressed up as well-intentioned feel-goodism, there's a little boy with a ticker that's about to poop out, and once in a while, just so we don't forget about him totally, we get a tender scene between him and his mom. (Elise does her damnedest to give the movie a bit of quiet grounding, and sometimes she's allowed to succeed.) But mostly, the rest of the hospital goes about its business as if its staff was unaware that anything out of the ordinary was going on downstairs. (Didn't anyone happen to look out the window and see ace hostage negotiator Robert Duvall barking importantly into his walkie-talkie?)

Beyond that, "John Q." is simply the kind of movie that doesn't serve Washington well. He can be a terrific actor, except when he's allowed to turn the righteousness faucet on full blast. That's when he loses the wonderful subtlety that made his villainous turn in last year's "Training Day" so fascinating to watch. He's a much better actor when he's not struggling so hard to be a role model.

Even worse than that, though, is the way "John Q." timidly dips its toe into important issues only to abandon them for cheap entertainment prancing around in faux sackcloth. Is it true that people die in this country -- the richest in the world -- because of inadequate healthcare? Yes. Are doctors often arrogant to mere civilians? Yes. Is there waste, excess and greed in the healthcare business? Yes. (Blue Cross/Blue Shield launched a preemptive P.R. campaign to reassure critics and viewers that help is available to almost everyone who needs a transplant, which suggests that, at the very least, healthcare organizations are aware of the public's suspicion.)

But "John Q." isn't really about any of those things. In the end, it's about a guy with a gun and a bunch of people who wonder what he's going to do with it. We've already got a million movies out there about roughly the same subject. At least they're honest about it.

Shares