As an actor, Bill Paxton is drawn to movies with a certain degree of moral complexity. Part of his appeal is that he has a face we want to love; but what makes him such a fine and fascinating actor, particularly in emotionally wrenching pictures like Sam Raimi's "A Simple Plan" (1998) and Walter Hill's "Trespass" (1992), is that he risks losing our sympathy at every turn. In those movies, he plays characters whose misguided actions cut against the grain of what we want to feel for them.

But even when we disapprove of a character's desires or motivations, the vulnerability and veiled pain in Paxton's face keep us from turning away. He has a knack for keeping us well on his side, for refusing to let us pass judgment on a character too easily. Any actor can forge a character who commits horrible acts of deceit and murder for reasons we can't comprehend; Paxton has a rare gift for making the unthinkable seem perfectly comprehensible.

You can see that sensibility at work in "Frailty," Paxton's directorial debut. You also see a dedication to craftsmanship, and a desire to make every frame count. But you also get a sense of good intentions derailed by a failure to seek and strike just the right tone. "Frailty" starts out, and ends up, as a thriller trying valiantly to show us layers of moral depth. But in between that beginning and ending, Paxton's vision (as well as that of Brent Hanley, who wrote the script) becomes wavy and indistinct, a blurry muddle of sensationalistic, prurient grisliness masquerading as a meditation on the nature of evil. That's the risk you run when you make an arty thriller about an ax murderer for the Lord.

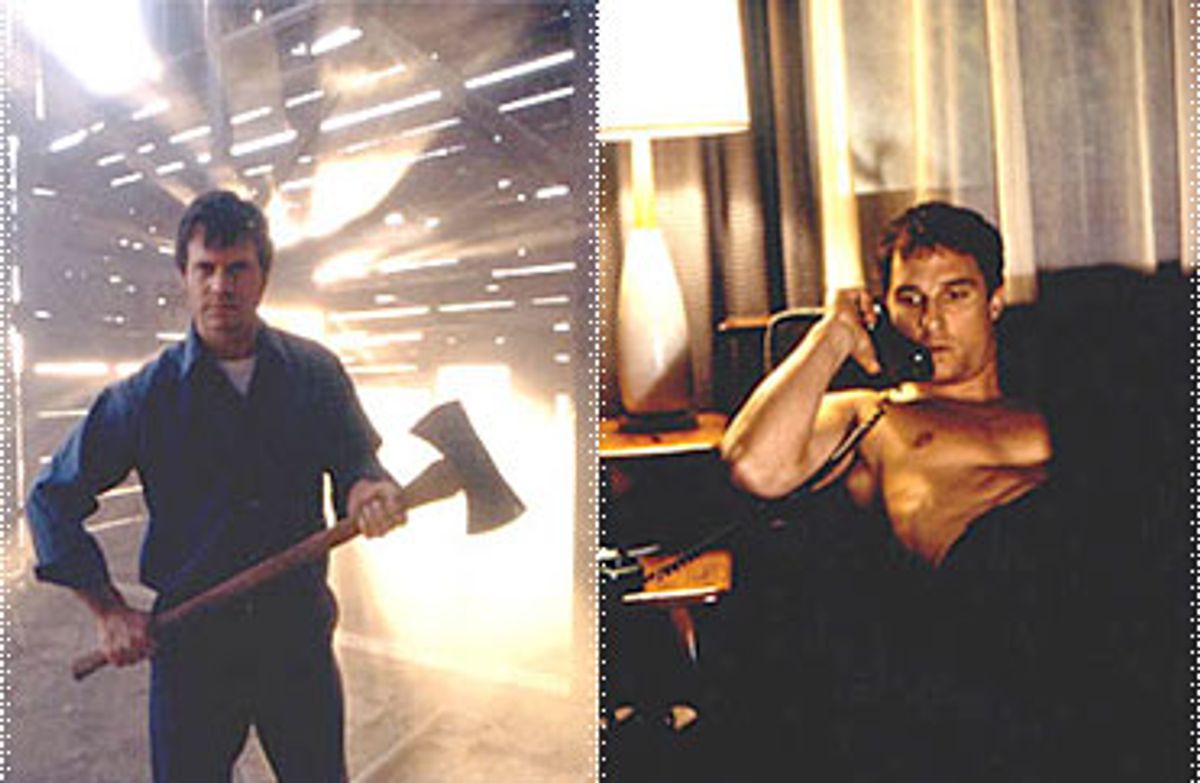

Paxton, in what may be the ultimate use of his heartbreakingly earnest, trustworthy face, has cast himself as that murderer. But he's also a loving widower and all-around good guy. The problem is that he's awakened one night by a vision from an angel of the Lord, who tells him that he and his two young sons, 12-year-old Fenton (Matt O'Leary) and 8-year-old Adam (Jeremy Sumpter), must embark on a mission to rid the world of the "demons" who walk it.

Of course, those demons are real people, and Fenton quickly catches on to the fact that his father has become unhinged. The more religiously devout and innocent Adam isn't so quick to get it, and participates somewhat willingly. Most of the story, which takes place in Texas, is told in flashback from the point of view of the grown-up Fenton (Matthew McConaughey), who is at last revealing the family secrets in order to help a detective (Powers Boothe) solve a string of gruesome murders.

Paxton wants us to feel the moral weight of the murders his character commits, which is probably why he shows those killings to us in such detail, as well as focusing on the boys' terrified faces as they're forced to watch or, worse, participate. But by the time we've seen our third bruised and bloodied victim, bound in duct tape and whimpering in fear, we've more than gotten the message. Instead of being drawn into the potential twists and complexities of the story, we're left dangling by the movie's relentless unpleasantness.

The killings aren't presented for our delectation -- Paxton is too sensitive a director for that. But how many times do we really need to hear the sharp thud of that ax cutting through bone and flesh? When Paxton (his character is known simply as "Dad") chastises Adam for merely tossing a garbage bag full of body parts into the secret grave the family has dug, it should be a grim joke when he shows the kids the proper way. (The angel has apparently instructed him that the bag must be emptied by turning it upside down and shaking it from the bottom, so that the parts spill out with a dull tumbling sound.) As it is, it's merely a queasy-making detail with no significant context.

That's a shame, because there are enough moments of "Frailty" that show Paxton in complete control, or at least having a clear enough vision of what he'd like to do. When we first meet Paxton, he's just coming home from his job as a garage mechanic, greeting his two boys, who have already started supper for the family. He jokingly admonishes Adam for spooning too many peas onto his plate; he asks the kids what's going on at school. Paxton, with his easy smile and soulful eyes, is the picture of comforting normalcy. That's why it's so devastating when he bursts into the boys' room in the middle of the night, switches on the light, and, in a completely sane-sounding, trustworthy voice, outlines his future plans for his family as if he were simply announcing that he was going to rent an Airstream and take them on a cross-country vacation.

Later, Paxton adds another twist when Adam presents him with a list of his own demons scheduled for destruction. Noting that one of the demons is a kid who has teased Adam in school, Paxton explains patiently that what Adam has done is very wrong. "These are real people, Adam." He goes on to explain the difference between killing demons and killing people, which, as the audience (and Fenton) knows, is no difference at all.

"Frailty" could have used more of that creepy subtlety and fewer of those bloody thumping sounds. But at the very least Paxton shows a desire to do good, thought-provoking work, even if the means to achieve it are just slightly beyond his grasp. But the buzzing undercurrent that fascinates him -- the idea that people with good souls can do truly horrible things -- is a universal theme that hasn't yet been exhausted by filmmakers. Paxton's got the knack of showing all that complexity on his face. He just can't translate it to a bigger canvas -- at least not yet.

Shares