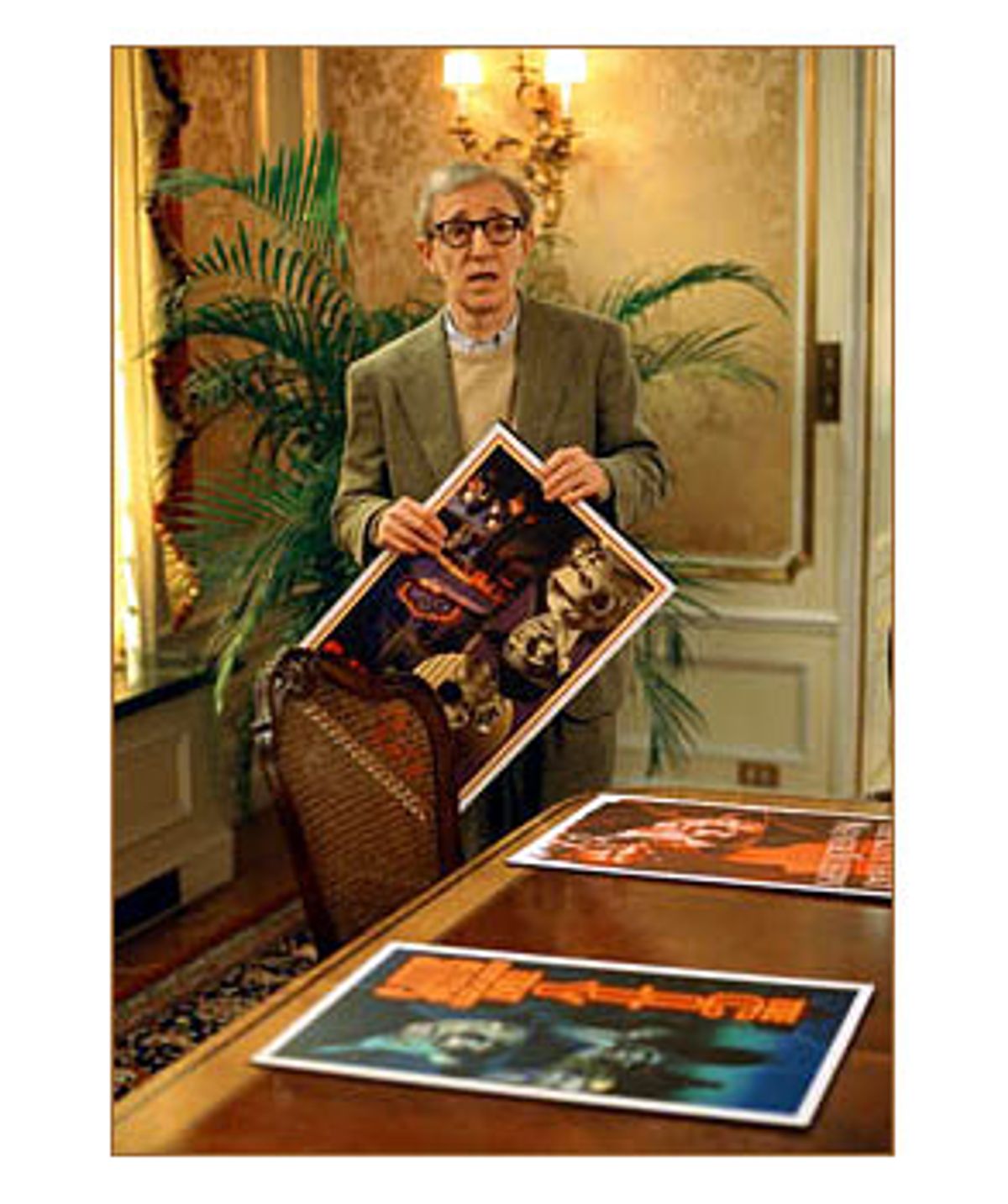

Woody Allen has been slouching toward irrelevance for almost 20 years now. What's remarkable about his slow trickle away from the forefront of American consciousness is not that it's taken as long as it has, but that he still manages to make it look like such hard work. No director in the history of moviemaking has expended so much effort in the service of drying up and blowing off the landscape.

In the '70s Allen was relevant, not least because he was a master at fashioning happily rough-edged works of pure pleasure: He distilled our collective intellectual anxiety into ramshackle rhapsodies that you didn't have to be either intellectual or anxious to enjoy.

But that was a long time ago. It would be nice if we could call it a tragedy that Allen's latest comedy, "Hollywood Ending," which he wrote and directed, is so inoffensively worn-in and faded that it leaves just a faint couch-potato shaped indentation on our brains. The sad thing, maybe, is that that's no surprise at all.

In "Hollywood Ending" Allen plays Val Waxman, a director who's fallen on hard times -- he's considered a has-been and no one wants to give him work. His ex-wife Ellie (Téa Leoni) is a Hollywood power player who persuades her bigwig studio-head boyfriend (Treat Williams) to let Allen direct a retro-'40s picture set in Manhattan, called "The City That Never Sleeps." She waves her arms emphatically as she tries to sell a team of Hollywood hotshots on her ex's suitability for the project: "The streets of New York are in his marrow!" Imagine what his liver must look like.

Waxman gets the gig, but not before Allen has established him as a supposedly sympathetic sad sack who, in life and in love, just can't get a break. He's got a real hot tootsie of a girlfriend at home (Debra Messing, in an overeager, paper-cutout performance), but she doesn't have a brain. Poor baby! Ellie, who was his second wife, started fooling around on him while they were still married. Poor baby! He has a grown son with green hair and multiple facial piercings who refuses to have anything to do with him. Poor baby!

Allen plays Waxman like a man who has spent his whole life innocently bumping through the universe, falling for dumb bunnies against his will (though it's no accident that Allen keeps casting attractive, much younger women as babes who can't resist him); not being able to keep a wife no matter how pathetically neurotic, childlike and in need of protection he makes himself look; and fathering children who are so selfish they simply refuse to understand how deeply self-absorbed he is. How can we not love a man so clearly born into such a world of suffering?

It's supposed to be terrifically funny when Waxman, just before the first day of shooting the movie that will either make or break the rest of his career, suddenly goes psychosomatically blind. Who ever heard of a blind movie director? But the gag would be funnier if Allen, as the movie's director and writer (he'd probably be the first one to use the word "auteur"), seemed to actually see the actors around him.

As it is, Allen has done little more than plunk himself into the middle of their universe, as the swollen-headed sun king around whom they're happy to revolve. Actors are always thrilled to work with Allen (or at least they pretend to be), but it's become almost impossible to see why.

In the past few years there have been a few who have held their own in his movies, despite the way his egotism bleeds, quietly or otherwise, into the margins of every project. In the reasonably entertaining "Sweet and Lowdown," Samantha Morton, as the mute girl who's madly in love with Sean Penn's scalawag guitarist, carried the picture without saying a word. (That's especially interesting since words are Allen's stock in trade.) And, in a much smaller role of a different stripe, the not-of-this-earth Elaine May quietly crept off with "Small Time Crooks." When Allen, as a bank robber turned cookie tycoon, approaches May at Ruby Foo's and, happy to see her, asks what she's doing there, her breathily straightforward response is like a one-sentence ode to the spacy brilliance of Gracie Allen: "I'm eating Chinese food. It's what you do in a Chinese restaurant."

There's still a certain amount of prestige associated with an Allen picture, which is why it's frustrating to see him cast wonderful comic actors (some of whom don't seem to get much work elsewhere) only to give them very little to do. Leoni has the looks of a '30s wisecracker and the timing of a safecracker; she was always a joy to watch in her ill-fated sitcom of a few years back, "The Naked Truth." Here she's nothing but a pretty reflector for Allen's neuroses (shouldn't he have trademarked that word by now, like Sominex or Geritol?).

Ellie used to be a regular gal when she was married to him; now she's an assertive Hollywood player, but one who hasn't completely lost her whimsical side. (We know this because she wears suits and shirts with impractically floppy sleeves.) Leoni never plays dumb -- when I'm watching her, even in a slow-moving vehicle like "Hollywood Ending," she always convinces me that of course legginess and braininess are exactly the same thing. Part of the fun of watching her is coming to your senses afterward, realizing you've been dazzled and bamboozled -- that's a component of her talent. But as Allen has written it, the role holds very little for her. And in the one scene where she and Allen kiss, she can barely hide what can only be described as restrained revulsion; she looks anxious to get away, like the pussycat beauty in the Pépé Le Pew cartoons.

Other actors float through the ether of "Hollywood Ending" as if they don't know where they are. George Hamilton's mere presence is funny: He haunts the movie as one of the Hollywood hotshots with an unspecified but very important job, dandling a golf club in his hand in every scene. It would be fine for Allen to use Hamilton as a jokey (and very tan) curlicue if he hadn't so clearly anointed himself emperor of the movie, but as it is Hamilton seems to have been cast and then forgotten. Barney Cheng, as a Chinese translator who helps Allen fool his cast and crew into thinking he can actually see, is wonderfully funny -- perhaps too funny. He gets the heave-ho after a few brief scenes.

And worst of all, "Hollywood Ending" just isn't very funny. The best joke is the most self-evident one: When Waxman finally regains his eyesight, he sits down in a screening room to watch the movie he made without being able to actually see the action. Peering through his fingers, he stammers, "This looks like the work of a blind man."

Unfortunately, "Hollywood Ending," which was shot by Wedigo von Schultzendorff, doesn't look so good either. It has a vaguely low-budget sheen, as if Allen were striving to give it more emotional authenticity, or, maybe, to make us forget that he's a big-time director.

The odd thing is, he wants us to forget how big he is but also to remember constantly, and he can't have it both ways. Positing himself as an anxiety-ridden babe magnet who -- poor thing! -- couldn't direct his way out of a paper bag is about the last thing a filmmaker like Allen should do to win favor with his audience. The ending of "Hollywood Ending" isn't much of an ending, either; it's more like the slow, saggy sigh of an expired whoopee cushion. And even then, Allen makes it look like work. For all his smarts, he still hasn't figured out how to poop out with a bang.

Shares