More than 25 years on, it's a little hard to explain "The Last Waltz." Rock 'n' roll, pop and hip-hop permeate our lives. The music blasts from commercials; you can hear the Ramones in the bar of an expensive restaurant; Joni Mitchell songs anchor an episode of "Ally McBeal." More than that, you can see rock -- and see it well -- on a slew of cable channels; fans can find exquisitely filmed concert footage (and fake concert footage) of virtually any artist they're interested in. More than that, the rock video industry, unaccountably, has found itself frequently setting the standard for film technology and construction.

In that context, it seems like no big news that you can see some rock stars in "The Last Waltz," recently released in theaters and just out on DVD. Its technical claim to fame is based on the fact that it was shot in 35mm. The group the film is about -- a band called just the Band -- were once somewhat famous but dropped out of sight around the time the movie was filmed, in 1976, and haven't been heard much of since. And the music they made -- today you'd call it Americana, or alternative country -- is as unfashionable a genre as you can imagine, the success of the yuppie coffee-table CD that is the "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" soundtrack notwithstanding.

The film "Woodstock," which came out about eight years before "The Last Waltz," contains head-snapping performances by Jimi Hendrix, the Who, Sly and the Family Stone, Santana and many others; it's a searchingly filmed and edited documentary of a larger-than-life event and remains a larger-than-life touchstone of an era of social upheaval and a landmark in documentary filmmaking. That film aside, however, "The Last Waltz," as the pristine DVD version attests, is the single best movie about rock 'n' roll and only rock 'n' roll ever made.

At the time "The Last Waltz" was created, the rock film was still a rarity, despite the magisterial "Woodstock" and the shockingly fun mid-1960s Beatles outings. You could see the occasional 16mm concert films -- "Pink Floyd Live at Pompeii," "Ladies and Gentlemen the Rolling Stones," "Ziggy Stardust" and so forth -- but only in theaters, and only in the cities that might have an offbeat movie house that would play such stuff. Rock appeared on TV only rarely (on cool shows like "The Midnight Special").

So, in 1976, when it was filmed, and 1978, when it was released, "The Last Waltz" had some striking features. The film chronicled a concert in which appeared not only the Band and Neil Young and Joni Mitchell and Eric Clapton but also Bob Dylan and Van Morrison and Muddy Waters, many of these at something near their psychic best. The occasion of the show was the announced retirement from the road of the Band. Even back then, the group was a somewhat mysterious ensemble, Canadian save for an Arkansan drummer but uncompromisingly dedicated to the investigation of American music. After nearly a decade of tangential obscurity, the members found themselves Dylan's electric backup band in the mid-'60s. Later they would hole away with him to make rock's most famous bootleg, "The Basement Tapes," and release influential records on their own, most notably "Music From Big Pink" in 1968. At their peak, they revealed a Crazy Horse-style force and Stones-like libidinousness, both leavened by a predilection for drolly fatalist Americana populated with R. Crumb-like characters and romantic losers.

The group planned its farewell at Bill Graham's Winterland auditorium in San Francisco. The band's leader, Robbie Robertson, knew Martin Scorsese, who was then in Los Angeles finishing up his wan tribute to the American movie musical, "New York, New York." He was so late on that film, and so over budget, that he had to undertake preparations for "The Last Waltz" secretly. Once he took on the project, he decided to do what apparently had never been done for a serious rock movie -- film it in 35mm, under controlled conditions. That meant turning Winterland from a concert venue into a film studio, with an appropriate set; stationary and moving cameras; storyboarded songs; and an intense communications network to capture what was needed to be captured -- all of this for a complex show with an array of special guests, and in an era when "authenticity" was a rock byword and many musicians and concert production people were less than cooperative when it came to sacrificing spontaneity to decent filmmaking conditions.

Scorsese brought in Boris Leven, who had been production designer on "West Side Story" and "The Sound of Music," to create a set; for cinematographers he had Vilmos Szigmond and Laszlo Kovacs, cameramen of choice for the "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls" generation. When Winterland's floor proved shaky, the production sawed through it and anchored the cameras in the building's foundation. Behind the stage, Scorsese built a rolling track for a moving camera. The San Francisco Opera lent the production pieces of a set from a recent production to create a lush and attractive backdrop.

After logistical problems that must have been nightmarish, given the egos involved, the concept came off. One of the things we learn on the commentaries on the DVD is that the group sent emissaries to the invited guests to find out what songs they were going to perform, to allow the Band to rehearse and prepare the proper arrangements, which could then be used by Scorsese for storyboarding purposes -- the solos, the change in vocalists and so forth. Promoter Bill Graham served the 5,000 attendees a Thanksgiving dinner; then, tables were cleared to make room for ballroom dancers. The show began with performances by the Band ("Up on Cripple Creek," "It Makes No Difference," "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, " Stage Fright," etc., etc.) alternating with tunes by the guests: Mitchell ("Coyote"), Young ("Helpless"), Muddy Waters ("Mannish Boy"), Neil Diamond ("Dry Your Eyes"), Clapton ("Further on up the Road"), Dr. John ("Such a Night"), Morrison ("Caravan") and finally Dylan ("Forever Young," "Baby Let Me Follow You Down"). There are two striking songs filmed later, on sound stages: "Evangeline," featuring Emmylou Harris, and "The Weight," with the Staple Singers. Then the show ends with an all-star ensemble singing "I Shall Be Released."

All of Scorsese's preparations combined to imbue "The Last Waltz" with a production sheen that, while never rendering the performance antiseptic or polished, gives it, paradoxically, a momentousness. Previous rock movies, virtually without exception, had been made cheaply and on the fly. This show, by contrast, was lit for high-quality filmmaking and was being shot by several of the most brilliant cameramen in the world; the performers' faces glow, become alive. Scorsese's extravagant plans -- a network of moving cameras and refocusing lenses -- combine to capture, seemingly, every nod and wink that passes between the artists. You can see the members of the Band, familiar with each other after 16 years on the road, each playing his part confidently and independently; but when others came on, you can see the members' antennae become alert; shrugs, glances, nods and smiles drive the concert forward. Scorsese humanizes the performance in a way that is without parallel in rock films.

There are a couple of guests who aren't that interesting, but most are spellbinding: Neil Young, spaced out of his mind on something, smolders; Joni Mitchell is a transfixing, alien-like presence; Dr. John fills the screen with wiseass geniality; even Ronnie Hawkins, the rockabilly lifer who gave the Band its start, mugs winningly. Dylan looks extraordinary with a beard, long, curly hair and a flamboyant pimp hat, and Morrison wears a spangled jacket over a purple shirt stretched tight over his barrel chest.

The Band themselves are revealed through their songs at the concert and through interviews with Scorsese that serve as a thematic intro to each song. In Helm's eyes, during the interviews, you can see a humble Texas kid, shy and wary; onstage he becomes randy and cheerful, reaching over to shake each guest's hand as they leave the stage. Garth Hudson, older than the others and more musically schooled, is the gruff professor. Danko, the goofy bass player, spends his time onstage rollicking, but offstage is simply unable to answer when Scorsese asks him what he will do next. And Richard Manuel, the keyboardist, has a maniacal charm; when Scorsese asks the band about women on the road, Manuel grins wildly and cracks, "That's probably why we were on the road so long."

Finally, there is Robbie Robertson, the band's leader. Robertson wrote most of the group's songs, letting Helm's mournful drawl and Danko's keening tenor animate them. There are a lot of ways in which the film is a love letter to Robertson, and a lot of other ways in which he is a politician; of the band members, he's the most controlled, the most guarded; and of all of them, he remains the most unrevealed. His songs -- piercing, funny, sui generis bits of cockeyed Americana -- remain unplumbed. We never learn -- we never get a hint -- of where those themes came from. That shadow is the film's biggest flaw.

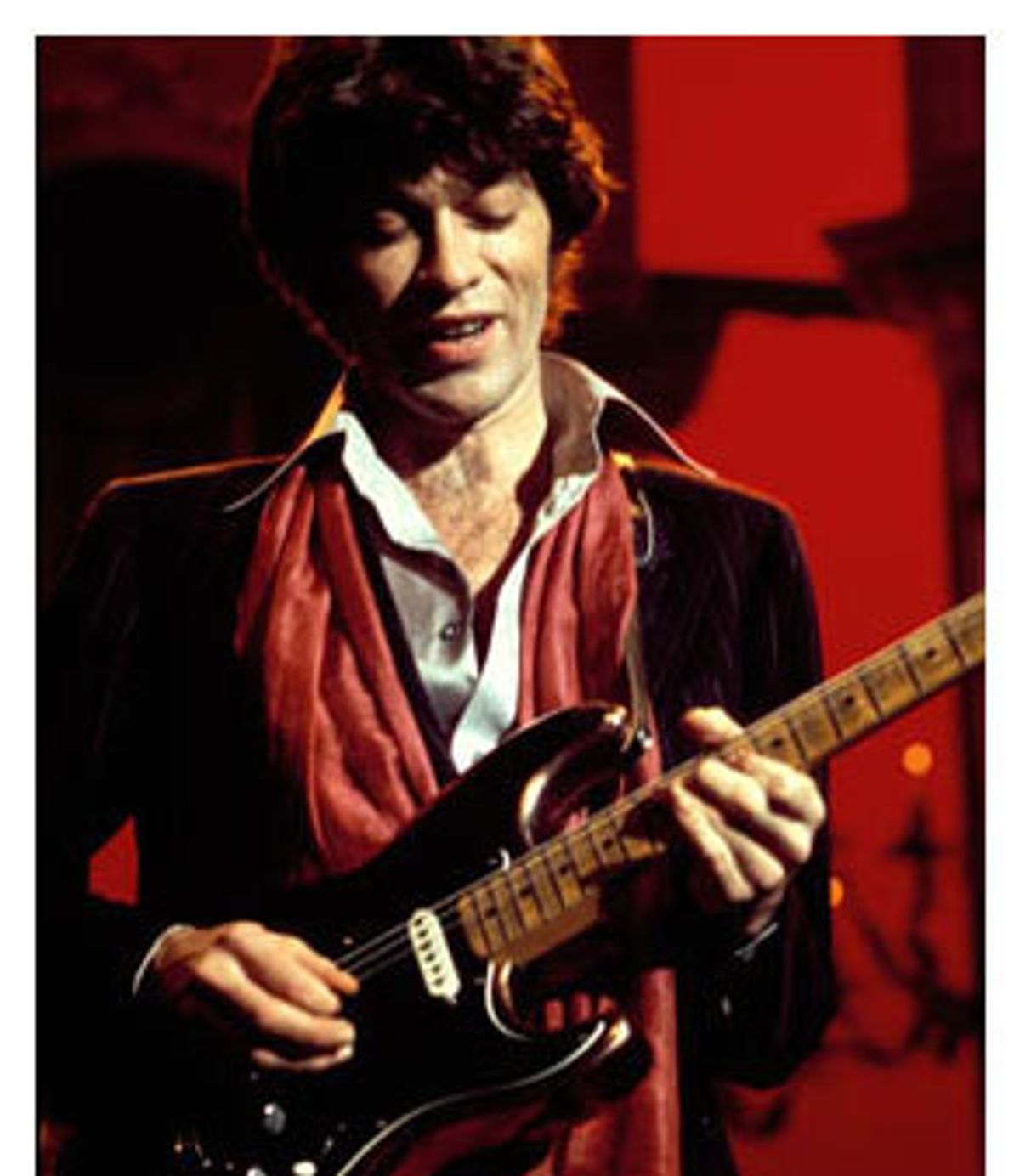

That said, Robertson remains a smoldering, leonine, sexy presence. He's featured in the vast majority of the film's scenes, strange for someone who doesn't sing. (Robertson has a rasp of a singing voice; it's said the other members of the Band snicker at how Robertson is seen contributing backup vocals on so many of the songs in the film.) But you see him, again and again, framed with his fellows, lost in his guitar or gazing with pride or wonder at the songs played out around him, and in the end it's hard to gainsay the film's focus; you can feel him draw the camera to him. Indeed, Robertson stands on the stage with Danko and Morrison and Dylan and Young and Clapton and holds his own as a songwriter, musician and sheer physical presence -- no small thing.

He remains a mystery on the DVD. There's an audio track in which he and Scorsese talk over the film. Scorsese is at his rapid-fire best, discoursing on Italian directors and frankly discussing the problems he had during the production; Robertson, by contrast, offers nothing but the highest praise for everyone involved.

The second audio track is a treasure. On it, a mass of people -- musicians like Dr. John, Helm, Hudson and Hawkins; critics like Greil Marcus and Time's Jay Cocks; and various film production people -- gleefully dish on the movie as it plays in front of them. Marcus, who wrote a book on the "Basement Tapes," patiently explains some of the themes of each of Robertson's songs as they come up; Cocks is at his best nailing the personas of some of the players, as when he calls Morrison a "half-homicidal elf." Even this supplementary material is searchingly edited, as when a halting Hudson rhapsodizes about the saxophone -- and we watch as he then steps up to the stage on-screen for a gorgeous alto sax solo.

In these scenes and a dozen others the heart of the movie beats, as well as in the rumbling Muddy Waters, the New Orleans shuffle of Dr. John, the hyperintellectuality of Mitchell, the molten Dylan, the earthy evanescence of Hawkins; yes, even in the chuckleheaded Neil Diamond. It's partly about that olio of sound, either unshakably American or unshakably informed by American music -- from Chicago blues to Appalachian gospel, from Celtic soul to Tin Pan Alley -- in all its unfettered and sometimes grimy glory, played by a group of malcontents and miscreants: Canadians, British guitar gods, Irishmen, chumps from Brooklyn.

The poignancy of "The Last Waltz" is this: That while all of the major stars present were still producing impressive work, it was, in fact, the twilight of their genius. (Only Neil Young, with "Rust Never Sleeps," would go on to record a reverberating album.) The era these acts represent is now a bygone one, however much some would like to think an act like Dylan or Young has relevance today. Still, it's worth noting that that era did exist -- not the '60s era, precisely, because everyone knows about that -- but a slightly faded and braver one. "The Last Waltz" is our best insight to a moment when the giants of the previous decade raged against time, in the shadow of an age that changed them all inalterably.

Shares