German director Tom Tykwer's movies are less about doomed romanticism than about romanticism that flourishes in the face of doom -- even at their most devastating, there's always something persistently optimistic about them. "The Princess and the Warrior," cluttered and obstructed with imperfections as it was, featured one of the most intense (and beautiful) love scenes in the history of movies -- and it was an emergency tracheotomy.

Perhaps more than any other filmmaker working, Tykwer (best known for his 1999 "Run Lola Run") believes in the persistence of love despite all earthly obstacles (poverty, the law, political strife, societal strictures) and unearthly ones too (greed, dishonor, pure evil). For Tykwer, love isn't a rose; it's a stubborn, hearty, comely weed that can grow just about anywhere.

Although there's been quite a fuss made over the fact that the script for "Heaven" was written by the late, revered Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieslowski (and his longtime collaborator Krzysztof Piesiewicz), the picture is largely pure Tykwer, with Kieslowski's sensibility flickering through it like the light behind a frosted-glass lantern. Kieslowski fans may not think that's a good thing, but I find the pairing inspired. Though I understand why people respect Kieslowski, I've never responded much to his work: I find his movies too remote and self-consciously artful to be moving. (That they're also very slow shouldn't necessarily be a liability -- but it sure doesn't help.)

In "Heaven," Tykwer almost seems to be mimicking the pace of a Kieslowski movie, perhaps in homage to the filmmaker or perhaps just out of deference to the material. Even if Tykwer leaves his strong stamp on the final product, it's clear he's aware that the movie is essentially a collaboration. The difference between Tykwer and Kieslowski is that Kieslowski sought poetry mostly in language and images; Tykwer seeks it in energy. Tykwer's filmmaking here is attenuated and precise, but even though the action unfolds slowly, it's always driven forward by a quietly fierce momentum. Tykwer understates the tension in "Heaven," but it's there nonetheless, a rippling sheet of muscle beneath the movie's calm surface.

Cate Blanchett plays Philippa, an Englishwoman who has been living in Turin, Italy, working as a schoolteacher. In the movie's first scene, we see her planting a bomb in the office of a businessman, although we have no idea why. The bomb ends up killing the wrong targets, and while Philippa had expected to be hauled off to jail for her crime, she's devastated when she hears how badly her plan has backfired. As she gives her testimony to the authorities, Filippo (Giovanni Ribisi), the young police officer who's acting as the official translator, finds himself not only sympathizing with her but falling in love with her, ultimately risking everything to help her.

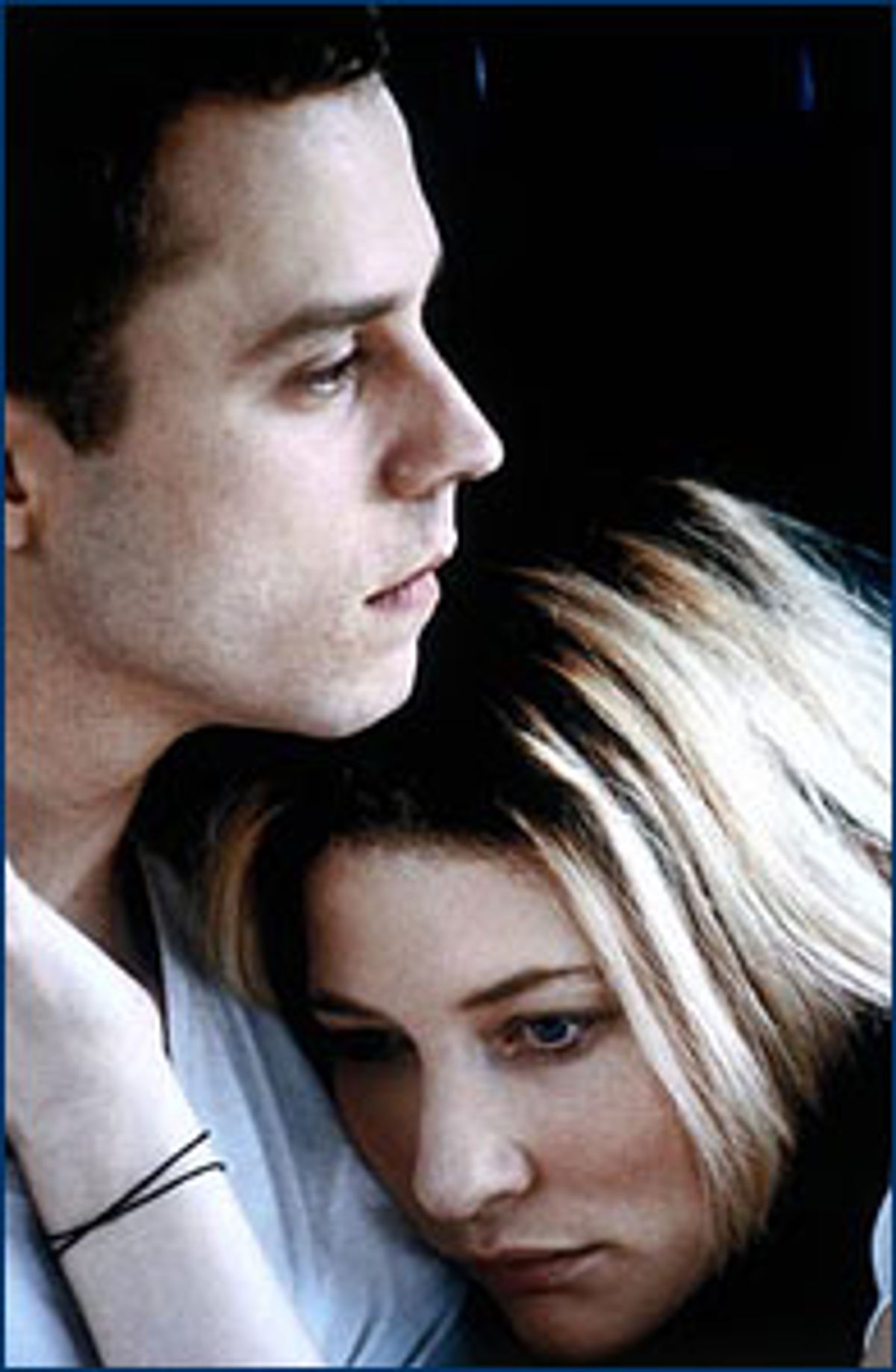

Tykwer is in love with the classic convention of lovers on the lam, but he hasn't worn it out yet. Instead, he consistently renews it: The sight of Philippa and Filippo sleeping curled into one another, more out of exhaustion than any false sense of security or even love, seems almost archetypal. And yet the way Tykwer shoots it, in soft, falsely soothing light, we feel as if we've never been privy to such a sight before -- its intimacy is familiar but also a little jarring.

Tykwer's actors seem completely clued in to his intentions. Both Blanchett and Ribisi give performances so restrained they're almost subliminal: The way their characters converse with and respond to each other is less significant than the way their minds and hearts seem to be connected by invisible spider-web threads.

Kieslowski and Tykwer are both extremely interested in morality, even though, as filmmakers, they've explored it in vastly different ways. In "Heaven," their sensibilities meld. The characters are driven as much by conscience as they are by love -- a tacit suggestion that the two are inseparable. Philippa has acted out of moral courage, and yet she's constantly aware of the grimness of her crimes; Filippo, in shifting his life around drastically to help her, tries to draw some of that weight off her.

Tykwer shows the lovers striding through the magnificent Italian countryside; two smallish figures set against massive sun-bleached green hills. They're isolated in their intimacy even in this wide-open space, and the way Tykwer and cinematographer Frank Griebe shoot it, that's both a comfort and a despairing truth.

There are places where "Heaven" feels more Kieslowski than Tykwer: Aside from the similarity of the characters' names, they grow to become similar in other ways -- they end up dressed alike in dark trousers and white T-shirts, and both shave their heads for no discernible reason. (If you were trying to hide from the Italian police, would you disguise yourself as a Hare Krishna?) That's the kind of philosophy-class term-paper theme that Kieslowski specialized in, suggesting that if you had to write a thesis about "Heaven" for a teacher, all you'd have to do is slap down something with "duality" in the title and you'd be sure to get an A.

"Heaven" just doesn't need that kind of swollen symbolism, especially with actors as attuned to each other as Ribisi and Blanchett are. And so many of the other ideas embedded in the movie are much more engaging anyway: Tykwer always seems to enjoy exploring the limits of male heroism -- he's much more interested in showing what happens when it's met halfway and matched (or surpassed) by the female version.

In "Heaven," both Philippa and Filippo get to be knights in shining armor, rescuing each other from their respective uncertain fates and striding toward a new one together. The future may be bleak, but they're glowing so brightly that they light it up. They're the definition of love in the face of doom, and they're inextinguishable.

Shares