David Gordon Green is so obsessed with naturalism that the worlds he creates seem hyperreal: They're so artificially natural that they end up feeling remote. Green's second feature, "All the Real Girls," shares that quality with his first, "George Washington," although the two are very different movies. The offbeat, rangy "George Washington" (2000) was a movie made up of some very careful dance steps, with Green showing us plenty of incomprehensible, or at least troubling, human behavior and then being sure to set up ways for us to understand it: A young teenager's cranky, inscrutable uncle kills the kid's scruffy pet mutt because he was humped by a dog in his youth -- and so forth.

Green is intensely sensitive to human fears and anxieties and trauma, and he sets them against landscapes of scrubby fields and junkyards that scream "real." And yet in both of his movies, you don't get the sense that feelings just happen; it's more that they've been orchestrated, wrested into place. Like a rusty old car that's been sitting on cinder blocks so long that weeds have grown up around it, they may feel somewhat natural, but they're not organic.

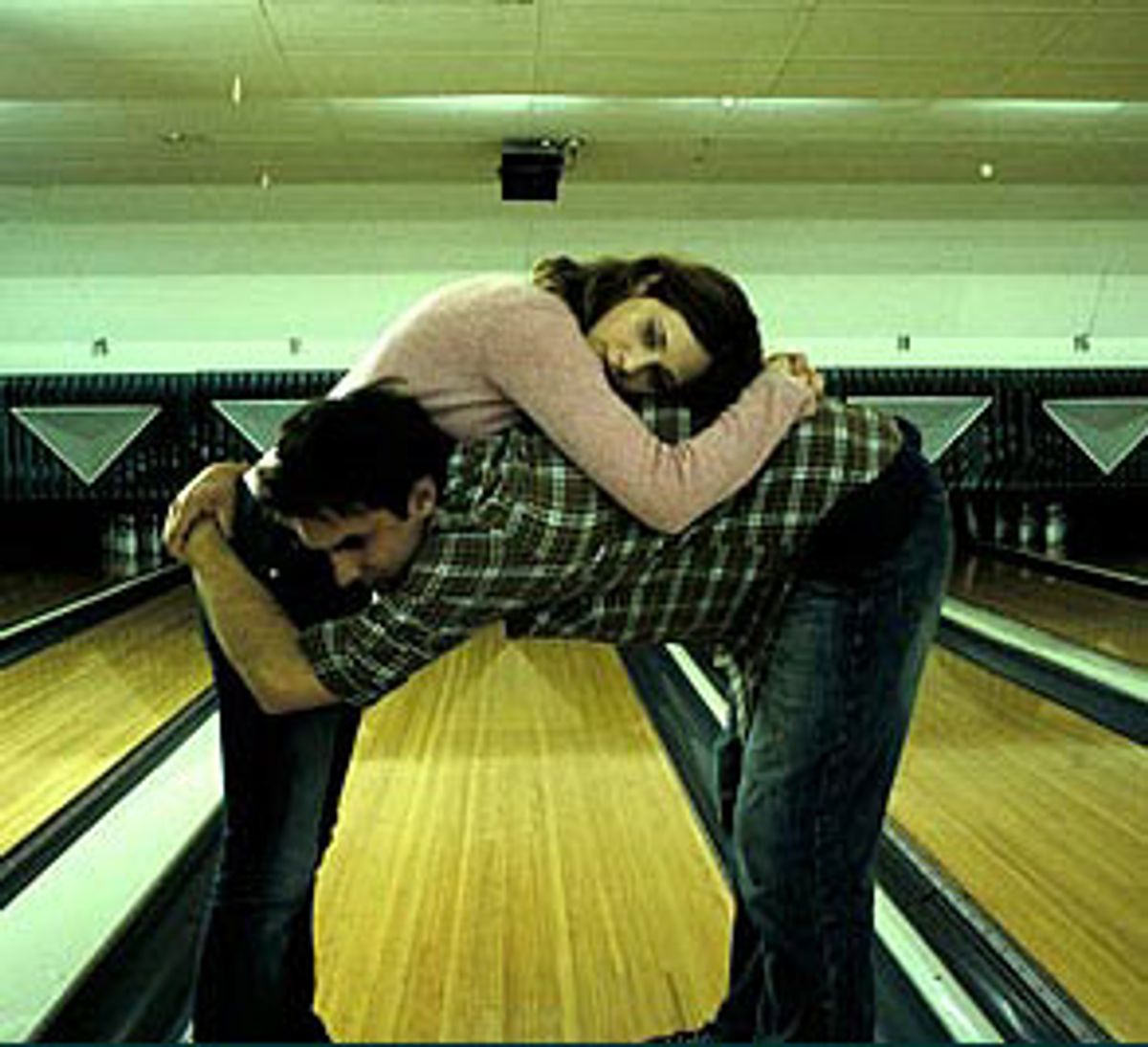

"All the Real Girls" is a love story set in a small, dingy North Carolina mill town, the kind of town where people stick around pretty much their whole lives. These towns exist in real life, and it's a good thing, too -- we need them for filmmakers to make movies about people who get stuck in one place. In this case, though, there's a character who actually had a way out and didn't take it. Noel (Zooey Deschanel) is a lovely oddball of a girl who, at 18, has just returned from six years away at boarding school.

It's never explained how or why a girl from this particular social milieu got to boarding school in the first place, or, much more significantly, why she would choose to return home after being exposed (we assume) to more of the outside world. But for whatever reason, she's back, and she's intensely attracted to Paul ("George Washington's" Paul Schneider), the town's Don Juan. She feels she can talk to him -- in fact, he's the first person she's ever really felt like talking to. And he, despite the fact that he's loved and left just about every other young woman in town, feels the same way about her, although his feelings confuse and bewilder him.

Young love! Green (who also wrote the movie's script) nurtures the couple's affections as if they were a tender sapling under threat of being bruised and buffeted by the real world. And, of course, they are. Paul and Noel don't rush into having sex because Paul doesn't want to treat Noel (who is a virgin) as if she were just any other girl. There's an age-old term for the feelings that ultimately rock Paul's world -- file them under "madonna/whore complex" -- but Green treats them as if they were a revelation of our modern world that somehow, like the latest dance craze, just reached Smalltown USA. There's nothing inherently wrong with that. There are no new stories, only new ways of telling the old ones, and it's every young filmmaker's right to take a shot.

But you can't shake the feeling that Green thinks "All the Real Girls" is fresher than it really is. He does attempt to treat this burgeoning romance with grace and delicacy. In an early scene, as Paul and Noel are just getting started, we see them huddled in the shadows, quietly trading secrets after a nighttime date. Paul kisses the palm of Noel's hand, a deeply romantic gesture and one whose erotic potential is largely underrated. In that first sequence Green does a great job of showing us their fragile, wobbly-kneed intimacy -- it's like a spring lamb -- and makes us wonder where on earth he's going to take us next.

Unfortunately, that's nowhere special. As Paul and Noel's relationship progresses, she utters lines like, "I had a dream that you grew a garden on a trampoline and I was so happy that I invented peanut butter," proving that the unedited sharing of dreams and feelings is truly one of the scourges of romantic love. Worse yet, Noel's older brother, Tip (Shea Whigham), who is also Paul's best friend, disapproves of the relationship, and it damages his friendship with Paul. As you can see, this is truly a town without pity.

The good news is that Deschanel doesn't make the mistake of playing Noel as a google-eyed charmer; she's off in the ether just enough that she can sometimes be fascinating to watch. As Deschanel plays her, you can't write Noel off as a cutie-pie flake (her dreams about garden trampolines and peanut butter notwithstanding); we see that she's really a refuge of resolve and good sense in this godforsaken town.

But Schneider's Paul just seems lumpy. Though we're told how cruel he's been to the other young women of the town (and we see evidence of it in a few brief flashbacks), he hardly has enough sexual presence to make us believe it. He seems like the sort of guy who almost doesn't have enough gumption to be nasty. His relationship with his very young mother (Patricia Clarkson, doing a valiant job in one of those unfortunate zany mom roles) is casual and close, but that doesn't give us a whole lot of clues about him as a person, either. We do know the two of them sometimes work together as clowns at the local hospital, entertaining sick children, and if you've got that movie metaphor textbook handy, you probably know that clowns are usually a symbol of hidden or repressed feelings.

But we need more clues about these young people -- more interior clues, as opposed to cleverly dropped ones -- in order to really understand them. At one point in their mechanically quirky courtship, Paul tells Noel, "I wanna dance, but I don't want you to watch." She turns her back, and he stands behind her for a moment before breaking into a wild yet awkward shimmy.

It's easy to see what the scene signifies: Paul yearns to be completely himself, with Noel or with someone, yet he just can't let go. But Green gives us far too many seconds to drink in this sight before cutting away, and every spare second tells us how pleased he is with this little scenario, with his unorthodox characters and their confused, fragile, wacky feelings. The sad thing about "All the Real Girls" is that Green seems more in love with his perceived unconventionality than he does with his characters. If that's not a town without pity, I don't know what is.

Shares