Apocalypse is very much on our minds these days, yeah. But then, it's been on our minds pretty much steadily ever since the summer of 1945. Every new generation of artists and musicians and filmmakers (and critics) gets to come along and find it waiting for them like the hidden treasure at the end of our civilization's rainbow, the logical end point for every story about a culture that seems bent on destroying itself.

Every movie I see seems to be about the end of the world these days, some literally and some less so. Next week brings us "Terminator 3," in which Arnold Schwarzenegger tries to save two cute kids from nuclear war. Mike Figgis' forthcoming experimental film "Hotel," which admittedly almost no one will see (although you should, if you're the masochistic art-film type), offers the spectacle of postmodern celebrity culture literally devouring itself. Later this year Frodo and Sam will save the world and end it at the same time, and Neo will have his climactic showdown with the agents of the Matrix. (I haven't seen "From Justin to Kelly"; that might be the end of the world.)

It's true that movies like "The Hulk" or Danny Boyle's new "28 Days Later" focus on specifically contemporary anxieties, on the idea that something inside us, something tiny, something we can't stop -- a reengineered gene, a renegade virus -- will lead to the destruction of everything outside us as well. In "28 Days Later," a megavirus accidentally released from a primate-testing lab (maybe it's a military weapon, but in the grand tradition of apocalypse films, its origins are not explained) has turned virtually the entire British population into murderous, ravening ghouls in less than a month. It's undoubtedly a canny and clever twist on the standard zombie-attack yarn, but anybody who's making grand claims for "28 Days Later" simply hasn't seen enough horror movies.

Screenwriter Alex Garland, who previously collaborated with Boyle on the flop film of his hit novel "The Beach," has cited the classic British dystopian sci-fi novels of J.G. Ballard and John Wyndham as influences, and they're in there, all right. There's also a bit of the "Road Warrior" films, a hefty dose of Stephen King's "The Stand," and even more of George A. Romero's "Living Dead" trilogy, specifically the underrated third entry "Day of the Dead," which is so closely emulated here that parts of "28 Days Later" feel like a shameless rip-off.

As a viewer, I have no problem with that (although Romero might). The essence of making genre films is absorbing other people's good ideas and morphing them into something new (see the "Matrix" franchise), and "28 Days Later," with its imaginative, often beautiful use of digital video and its startling visions of the central London landscape totally abandoned to the rats and pigeons, makes at least partway good on that promise. But this movie also confirms my feelings about Boyle, going back to his early hipster-cred successes with "Shallow Grave" and "Trainspotting": He's an ingenious craftsman with a keen sense of style, but he rises and falls with his material, and he lacks the intuitive sense of pacing and construction, the passion and commitment, that separate great directors from able ones.

To return to the Romero example, "28 Days Later" has better actors than "Day of the Dead" and is far superior on a pictorial level. As the tiny band of virus survivors in Garland's screenplay make their way northward through an England of useless machines, abandoned supermarkets and undead "infecteds," cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle creates one breathtaking composition after another. In this film the innate potential of the digital-video medium -- its ability to capture a subtly troubling chiaroscuro effect, not unlike that of late medieval painting -- is more fully realized than ever before. Yet "Day of the Dead," in its primitive, intense depiction of a subterranean human community trapped in a zombie world, is a clammier, more claustrophobic and ultimately unforgettable film. It weirds me out right now to sit here and think about it, whereas "28 Days Later" is likely to roll off me in a few days and wash away in the tide of mental clutter.

None of this will matter much to viewers who aren't accustomed to seeing horror movies, which probably describes the core demographic for Boyle's film. Almost any viewer, however, regardless of his or her ability to write a comparative dissertation on the zombie flicks of the '70s, will be able to tell that "28 Days Later" starts out with an astonishing premise and gradually paints itself into a dumb little corner.

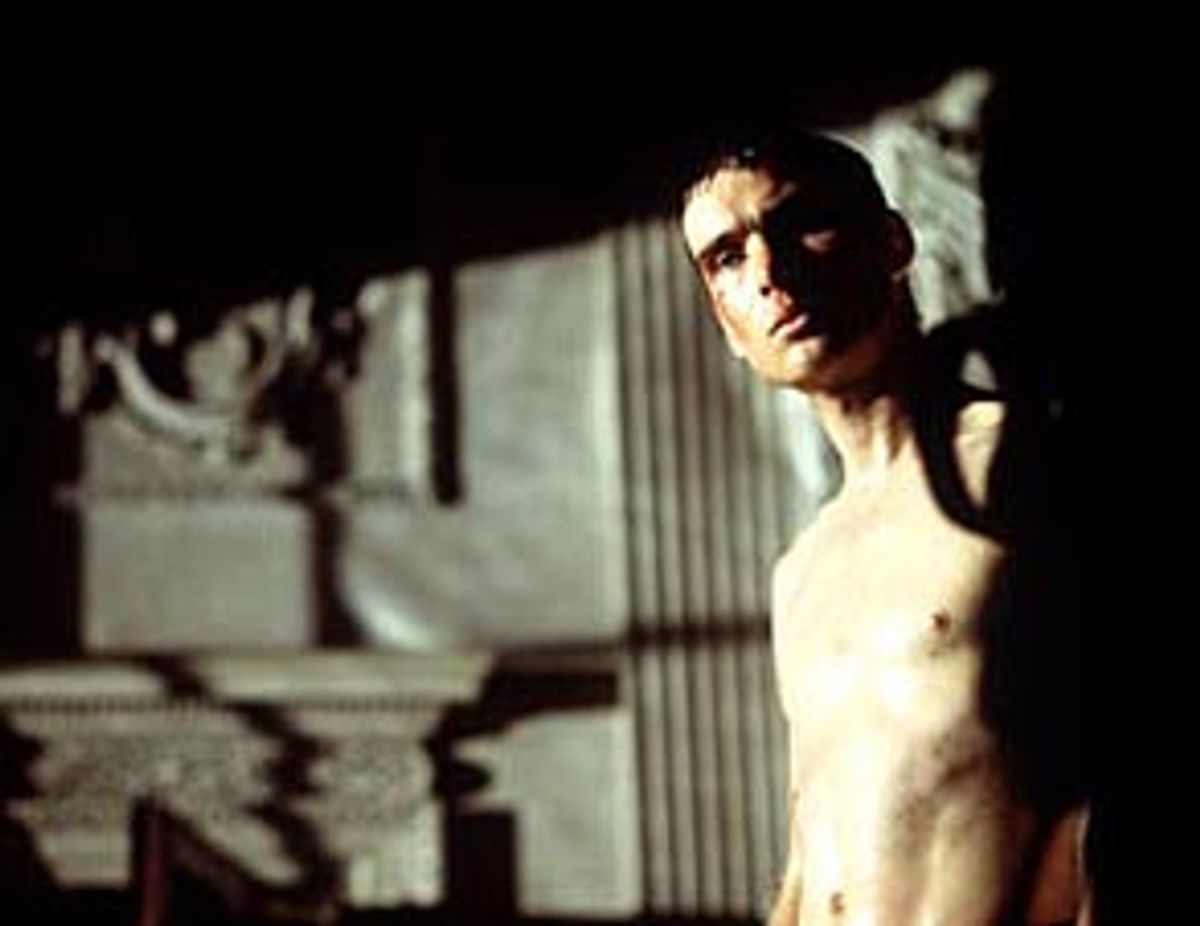

From the moment soulful-eyed Jim (Cillian Murphy), a coma patient in a London hospital, wakes up to the extraordinary sight of the abandoned city around him, the questions begin to mount. OK, so everybody's either dead or a flesh-eating zombie, but where are all the bodies? What happened to all the cars? Why haven't the infecteds eaten the pigeons and rats? For that matter, why haven't they eaten each other? (Perhaps they have, bones and all.) Are good-looking coma patients always kept naked in their hospital beds? So the staff can ogle them or what? And isn't "I was in a coma and missed the end of the world" the lamest excuse known to the narrative arts?

Even the fact that these questions come up suggests that Boyle isn't fully in control of his instrument here. "28 Days Later" is loaded with terrific images and extraordinary little moments, and it's watchable entertainment from beginning to end, even as it inexorably deteriorates into Scooby-Doo terrain. But it never clamps you down in an iron grip the way horror movies should, commanding you to abandon all disbelief and surrender to undiluted paranoia. It just sort of drifts along through its remarkable pictures, throwing in the odd shrieking-demon along the way. Maybe Boyle really hasn't seen Romero's pictures -- he sure didn't learn anything from them.

Jim wanders the streets, fights off the assault of a demonic zombie priest -- almost the only scene that evinces Boyle's "Trainspotting" black humor -- and begins to piece together the fact that the unthinkable has happened. Eventually he hooks up with a pair of survivors hiding out in a convenience store, Mark (Noah Huntley) and the lithe and lovely Selena (Naomie Harris). These early scenes, as the trio roams the abandoned malls and office buildings of London's sterile Docklands district, scavenging for candy bars and warm cans of Pepsi, are perhaps the film's most potent and realistic. (In any tale of apocalypse, it's the little things -- the ordinary, meaningless debris of civilization -- that assume an unexpected poignancy.) After a disastrous trip to find Jim's parents in suburban Deptford, Jim and Selena find refuge in another hideout, with a father (Brendan Gleeson) and daughter (Megan Burns) who've built their own little fortress in a high-rise apartment building.

Running out of food and water, this foursome heads north from London to Manchester, in search of the source of a mysterious radio signal, which promises a force of "soldiers" and "the answer to infection." Where they're actually going, of course, is into one of those lessons that come at the end of sci-fi movies, a lesson about how humans revert to barbarism in extreme circumstances and how the cure is sometimes even worse than the disease. They end up in a wacked-out military encampment in an old country house, presided over by a Colonel Kurtz type (Christopher Eccleston) with big dreams. One of his more philosophical underlings suggests that human beings themselves are an aberration in the history of the planet: "If the infection wipes us all out, that is a return to normality."

That guy might have a point, but by this stage "28 Days Later" doesn't. It's lost any pretense of edge or originality it once had and has become a standard-issue smash 'n' slash with some cool cinematography. That's not remotely a crime; I enjoyed watching this film, mostly because Murphy and Harris make such an appealing central couple to build a new world around. (Each of them, I predict, will make a significant impression in British and international film.) But nobody should mistake this for a killer-zombie movie with real soul.

Shares