I don't believe movie audiences are becoming more stupid over time. But I do believe, unfortunately, that plenty of today's filmmakers assume their audience is brainless. They streamline and simplify everything, telegraphing their meaning and intent not just with noisy clicks and clacks but with sonic booms. Instead of assuming that most of us are somewhat adept at reading the language of moving pictures (which have, after all, been around for about a hundred years now), they've perfected a clumsy Morse code for the movie-impaired. Never seen a movie before? No problem. You can't get lost if there's nothing to get lost in.

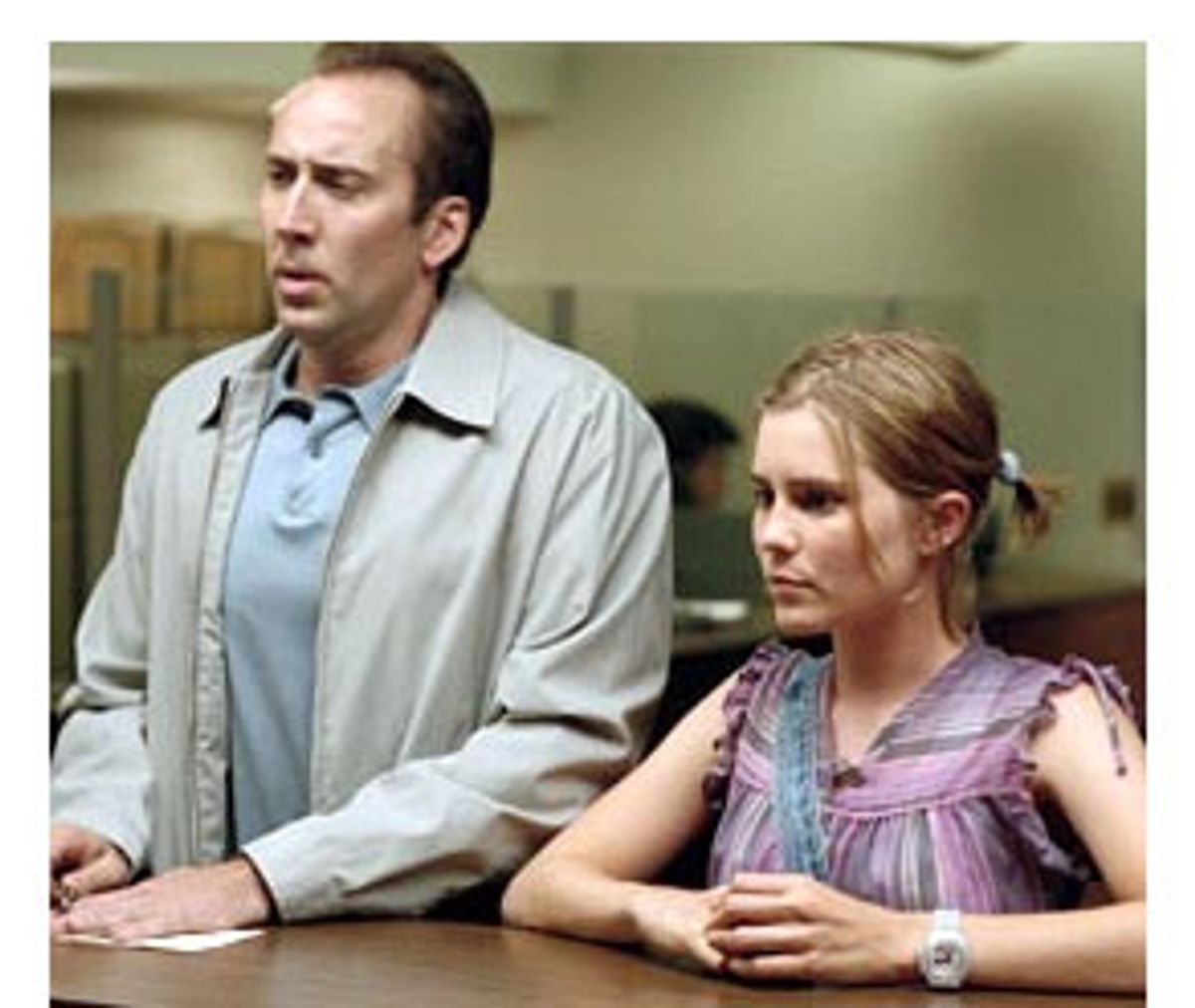

With "Matchstick Men," a heartwarming tale about a pair of ruthless grifters, director Ridley Scott and writers Nicholas Griffin and Ted Griffin (working from Eric Garcia's novel) snuggle right up to an imaginary audience of movie virgins. Roy (Nicolas Cage) is a veteran con artist with a heap of personal problems, including an obsessive-compulsive disorder that causes him to fixate on the cleanliness of his carpet (among other things) and a passel of repressed, regretful memories of the ex-wife who walked out on him years ago. His younger partner, Frank (Sam Rockwell), has fewer personal problems but also a lot less cash: While Roy lives off the fruits of his life's work in a swanky suburban ranch house, Frank is stuck in a cramped, messy crib. Tired of working small-time cons, Frank wants Roy to pull off just one major swindle. Almost simultaneously, Roy's new shrink (played by Bruce Altman) persuades him to reconnect with the child he and his wife conceived before they split. And before long, Roy is playing the awkward role of daddy to his newfound daughter, Angela (Alison Lohman), a skateboarding wisecracker of 14 who doesn't seem to like her mother too much and who swiftly moves into Roy's space, disrupting his neurotically tidy household.

If you're ultrasensitive to spoilers, you might want to stop reading here. Then again, you probably shouldn't see "Matchstick Men" at all, since Scott gives away the game in the movie's first third. This isn't a case of a director intentionally handing us the ending so we can be surprised and delighted by the intricacy of the story as it works itself out. "Matchstick Men" isn't even remotely intricate; it's not even particularly interesting. Part of the fun of con-man movies is that we're invited to relish the nastiness of these bright but unscrupulous criminals as they carry out (and get away with) deeds we'd normally disapprove of. But in "Matchstick Men," there's no delight to be taken either in the scams (one includes bilking the commonfolk with a variation of the bait-and-switch routine; another involves the old briefcase switcheroo) or in the characters who pull them off. Rockwell at least has a bit of sleazy charm, and he gets one offhandedly funny bit: When the germ-phobic Roy asks him to clean off the phone after using it, he devilishly wipes it first on his butt and then on his crotch. And Lohman (who was intriguingly low-key as Michelle Pfeiffer's daughter in "White Oleander") has a glittering mischievousness here that Scott doesn't seem to know how to use to the movie's advantage.

But Cage, who's sometimes a marvelous actor and sometimes a tiresomely predictable one, does little more than practice some choice acting stunts here. His character has a nervous tic -- a great opportunity for Cage to show us that he's perfected the drama-school eye twitch. Cage is at his best when, just after he and Angela have pulled off their first father-daughter flimflam, he sends her back to return the filched money to the victim. He's both funny and touching in the way he announces authoritatively, "I would not be a responsible father if I let you get away with this."

But he's less adept at the murky sentimentality the movie asks of him. He looks out of place and awkward in a scene, set in a bowling alley, where he gets all dewy-eyed over his newfound state of fatherhood. (The fact that Scott scores the scene to Roxy Music's "More Than This," maybe the loveliest pop ballad of the '80s, makes it even more of a syrupy tragedy.)

"Matchstick Men" doesn't know what kind of a movie it wants to be: Is it a scam comedy or a misty father-daughter adventure story? At times it's disjointedly whimsical; other times it's faux-tense. Smart filmmakers often use tone shifts to great effect, but "Matchstick Men" simply feels uncertain about what mood it's supposed to strike.

Maybe Scott expects so little of us as viewers that he doesn't think that matters so much. There are still directors working in the mainstream who delight in giving movie audiences a challenge to rise to: Brian De Palma is the clearest example. On his good days, at least, Steven Soderbergh proves he knows how to make pictures with a tricky sense of adventure. And there are always newcomers to watch for: F. Gary Gray's "The Italian Job," for instance, is proof that it's still possible to make an action movie that's intelligent, satisfying and fun.

Scene for scene, "Matchstick Men" isn't horribly made. It's perfunctory and professional, a picture that has a plan and sticks with it, as if it were methodically following its own to-do list. At this point, Scott seems to know the ropes so well he could probably make a movie in his sleep. Maybe he already has.

Shares