With "Mystic River" Clint Eastwood has invented a new movie subgenre: neighborhood noir. In both the movie and the Dennis Lehane novel on which it is faithfully based, neighborhoods aren't comforting places; they're menacing ones, where the jovial, longtime buddy you pass on the street knows not just all your secrets but all your weaknesses as well. The type of siding that covers your house betrays your class and your educational background, not that those matter much anyway.

In the working-class Boston neighborhoods of "Mystic River," the most feral and the most ruthless creatures become the natural kings, and anyone who's too sensitive or too damaged needs to be sacrificed for the good of the tribe. Yet even if Eastwood's (and Lehane's) view sounds steeped in cynicism, it's really a kind of raw mournfulness. "Mystic River" is hard-boiled beyond toughness: It's so tender the skin falls away from the bone. It's Eastwood's most soulful, and most organic, movie.

Over the years Eastwood has been revered as a director for reasons that probably have more to do with iconography than with actual talent: As an actor, he's always been rugged and laconic, a product of the wised-up, weathered-barn school of masculinity -- a handsomer version of the American Gothic guy, with a handgun instead of a pitchfork. Similarly, the movies he's directed are quintessentially American, sturdy and straight-shooting, maybe, but often lacking grace and an innate sense of rhythm: To draw an analogy from one of the American art forms Eastwood loves best, they're like jazz ruled by the metronome and not by the heart.

Sometimes there has to be a kind of mad messiness to great art, and Eastwood is all about neatness and control. His movies, more often than not, feel like missed opportunities. The 1989 "Bird," about an American outsider who was also one of our greatest artists, and the 1995 "The Bridges of Madison County," about a tender extramarital affair, were both rich with possibilities for exploring the way the American sensibility supposedly encourages passionate exploration, only to put a lid on it when things get too hot.

Yet both movies feel cool and detached and rigidly respectable, not to mention just plain clunky: They strive to be great movies, but they're really just movies erected as symbols of greatness. Eastwood's 1993 "Unforgiven," with its elegiac brutality, cuts closer to the bone than probably any other Eastwood picture, and, unlike most of them, draws real blood instead of the squib kind. Mostly, though, Eastwood seems at his best (and most relaxed) in throwaway entertainments like the 2000 "Space Cowboys," movies made for fun and not for the pantheon.

"Mystic River" isn't a complete departure from Eastwood's usual mode of filmmaking, but it is a refinement of it. The scenes are filmed and connected with Eastwood's usual careful deliberateness. Certain shots and motifs from early in the film (a cross; the vision of a boy being whisked away in the back seat of a car) are echoed later. They're good images, but there's also something a little textbookish about them. Even though we feel like good film students when we seize upon them, they momentarily jolt us out of the movie's inner world, pulling us above the surface of its dreamy, dusky sadness.

That may seem overly picky, but it's worth mentioning because "Mystic River" is almost instantly absorbing -- it doesn't so much hook you in as envelop you in a treacherous, vaporous embrace. The picture moves forward with assurance and ease; it's as if Eastwood's by-the-book confidence has settled into something like a steady, human pulse.

The movie is set in a fictitious blue-collar nook of Boston called East Buckingham, but it's made-up in name only. As Eastwood shows it to us -- and as Lehane, a Boston native himself, described it so perfectly in his book -- it's a dead ringer for specific areas of the city, like South Boston and Charlestown, marked by clannishness, familial bonhomie and sharp distrust of just about anyone who's not white and of Irish descent. "Mystic River" opens in the mid-'70s. We meet three boys who are friends not because they like each other, exactly, but because geography and circumstance have thrown them together.

They're playing in the street one afternoon, scratching their names into a panel of fresh cement with a stick, when a car pulls up and out steps a thuggish fellow pretending to be a cop. He sizes up the boys in an instant -- their names are Sean, Jimmy and Dave -- and decides that of the three of them, the trusting, far-from-street-tough Dave is his easiest mark. The guy orders Dave into the car, where another "cop" waits. They say, with the kind of tough-guy surliness that would be perfectly believable cop behavior to a 10-year-old, that they're going to drop Dave off at home to tell his mother that he's been defacing public property.

But what really happens -- as we intuit quickly, with sinking hearts -- is that the men abduct Dave and sexually abuse him for several days. He manages to escape and return home, where he's welcomed back with supposedly open arms. But he is, as one of the other boys' fathers notes grimly, "damaged goods."

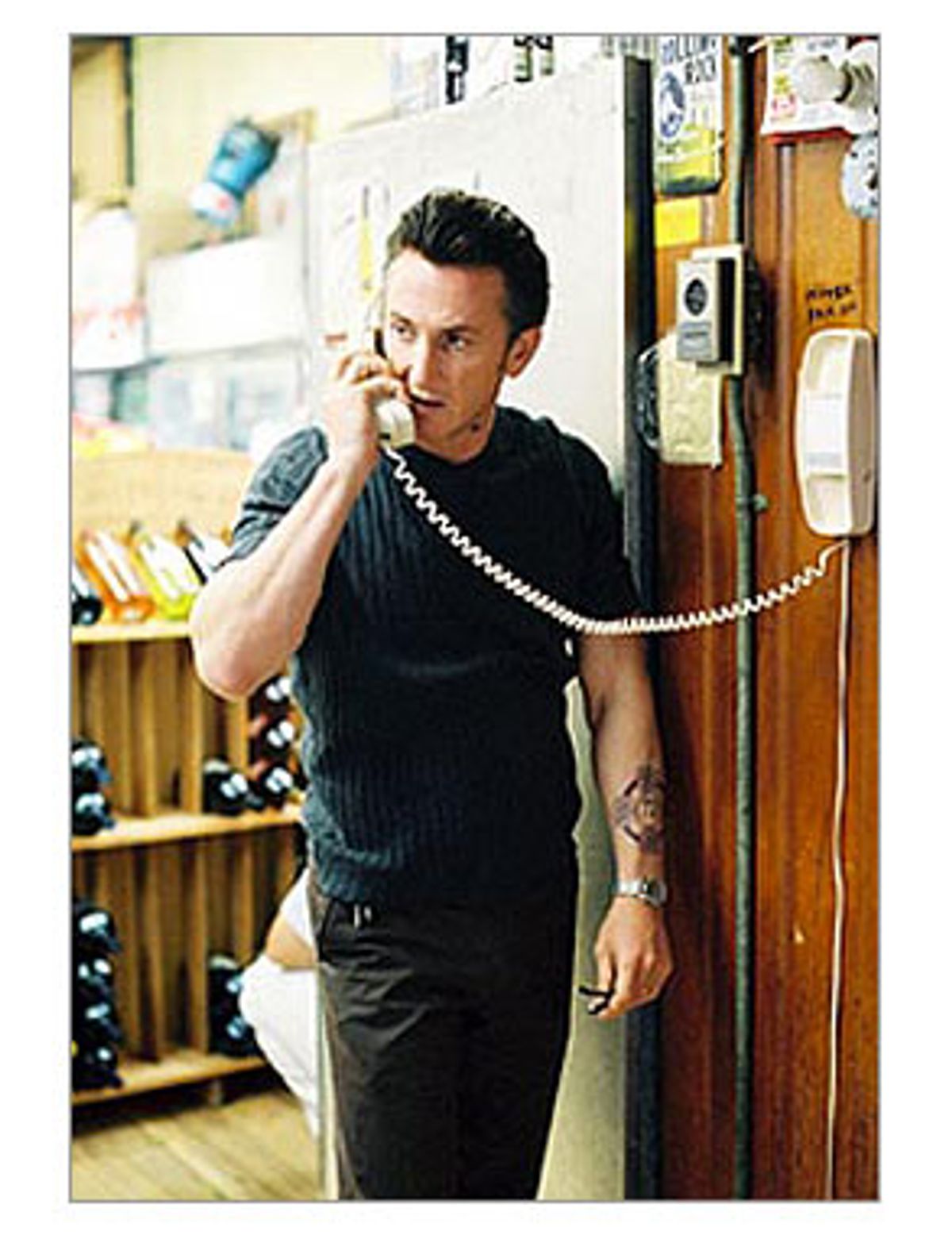

The three kids grow up and apart, without ever leaving the environs of the 'hood, at least not permanently: Sean (Kevin Bacon) is a cop who knows something of the world and yet feels rooted to the old neighborhood. But emotionally speaking, he's adrift; his pregnant wife has taken off with another man. Dave (Tim Robbins) is the kind of guy who takes a patchwork of jobs to support his wife, Celeste (Marcia Gay Harden), and kid, but who drifts through his life as if he were waiting to reclaim it instead of actually living it. And Jimmy (Sean Penn) is an ex-con who now runs a popular corner store and who seems to have settled into a kind of dual-sided respectability: He's an upstanding, law-abiding citizen, but one who wouldn't be above knocking your teeth out if you looked at him crossways.

Jimmy's 19-year-old daughter, Katie (Emmy Rossum), has been brutally murdered; Sean is one of the investigators assigned to solve the crime. (His partner is played by Laurence Fishburne.) Dave, whose traumatic childhood experience has marked him permanently as an alien in the community (he's a victim twice over, and the second time there's no possible escape), becomes entangled in the case: He was one of the last people to see Katie alive, and he horrifies and frightens Celeste by showing up at home late that night with a knife slash across his stomach and his clothes soaked with blood.

There's rough poetry in the way Eastwood unravels the story and the network of connections between the three men: His screenwriter, Brian Helgeland, has captured the rhythm and lilt of South Boston speech in every line. (If you've read Lehane's book, you'll notice that much of the picture's dialogue jumps to life on screen word-for-word.) Cinematographer Tom Stern gives the movie a sheen of friendly but dispirited menace, showing us tidy yet cheerless neighborhood streets in which the houses have been kept up more out of duty than of genuine pride of place.

Even beyond Eastwood's admirable, note-perfect choices, there's something about "Mystic River" that shocked me: I don't think I expected to see so much empathy in a Clint Eastwood movie. Empathy is often viewed as a largely female trait, probably because it's simply convenient, rather than accurate, to think of it that way. But in "Mystic River," the women aren't used as vessels of compassion. In some ways, they're more ruthless than the men.

Laura Linney plays Annabeth, Jimmy's second wife and the mother of two of his three daughters (his first wife died while he was still in prison, after having given birth to Katie). Annabeth's pretty, heart-shaped face makes a convenient disguise for her Lady Macbeth-like resolve; Jimmy has plenty of backbone, but she's standing by with extra, just in case. Dave's wife, Celeste (played in a beautifully calibrated performance by Harden), is a dutiful wife and mother who nonetheless seems to have given up on attempting to make Dave happy, let alone understanding him. Without ever coming out and saying as much, she lets us know that she really would have preferred one of the other neighborhood husbands: capable, conventional, shallow and untortured, someone who would be a good mate and father and not make many waves.

Eastwood knows more about his male characters than even their wives do. He has a reputation, carefully cultivated over many years, as an exceedingly manly actor and director who understands men and understands 'em real good, damn it. And it's true that he's well acquainted with the nuts and bolts and lugs of machismo -- in other words, he's sympathetic to notions of manly duty and honor, an A-plus student of the "man's gotta do what a man's gotta do" school of emotional efficiency.

But Eastwood's view of manhood has always seemed cartoonishly flat compared with those of other directors who've built careers obsessing about the overlapping layers of masculinity, machismo and honor -- Sam Peckinpah and John Woo, to name just two great filmmakers who have done it well. "Mystic River" changes that. You could argue that it fits with Eastwood's grand vision to feel sympathy for a guy who was abused as a kid -- ordinarily, in Eastwood's view, the innocent underdog should be protected. That's what heroes do: They take care of the weak. The trouble is that that's simply another way of patronizing them.

But Eastwood takes a more subtle tack in "Mystic River." For one thing, he cast Robbins in the role, and Robbins is a tall guy who certainly looks like he can take care of himself. Robbins uses every inch of that height in his performance: His walk is stooped, not as if he's been beaten down, but as if he believes that by curving his body inward, he can protect his tortured thoughts until he can sort them out and dispatch them once and for all. The movie's attitude toward Dave is very clear. When Eastwood casts his male gaze on Dave, he doesn't see a feminized object ripe for his benevolent, masculine pity. Instead he slips us right into Dave's skin, and silently asks the question, with all the outrage it demands: What must it be like to be a man, in a community like this one, when a sexual crime that's been committed against you counts against you?

Eastwood's view of the other two characters is no less complex. Sean is the good soldier, the guy who follows the rules and does just as he's told. But as Bacon plays him (in the finest performance the actor has given in years), we can see the ways he's both aching to break out and desperately trying to fit in. He doesn't like being a lonely, unmarried guy, left alone with his own confusion; he wants a wife by his side. And yet there's something about him that doesn't quite fit, either with the other two characters or with this overly familiar neighborhood. Where Jimmy is driven to act by adrenaline rushes and not by reason, and Dave is too frozen to act, period, Sean reasons everything out before he makes a move.

Bacon plays Sean like the guy in the middle, the decent fellow with more good sense than anyone and yet the one who's most aware of his own shapelessness: If Dave is filled with unnameable hopelessness and Jimmy is filled with pure rage, Sean is filled with decency, and he knows how colorless and ineffectual it makes him. Bacon pulls off one of the hardest things for an actor to do: He shows us the drama inherent in being the regular guy.

And yet it's Penn's Jimmy that we feel the most for -- partly because Eastwood feels the most for him and partly because Penn inhabits him so viscerally. This is the most complicated type of love I've ever seen in an Eastwood movie. The character for whom you feel the most sympathy is also the one who has the most to answer for, the one who, by every prescribed moral code, should draw out our disapproval and disgust. We recoil from him, and we also recognize how safe and warm we'd feel if we were under his protection.

Jimmy's mouth is permanently turned down into a clown's scowl, and that's even before his daughter is killed. But his love for her, a love that's simultaneously easy and firm, is never in doubt. We see them together in just one scene, early in the movie, and we feel the affable devotion between them -- in this relationship, she's the tiger, youthful and ready to spring at life, and he's the pussycat, a crotchety tom whose noisy purring mechanism betrays his capacity for love and pleasure.

That one small scene sets us up for everything else Penn does in the movie. In the first few hours after his daughter goes missing, he doesn't worry about her much; but when he realizes that Katie's car has been found, empty and bloodied, and that police are searching for a body in a nearby park, he crashes the crime scene, attempting to push his way through a scrum of blue-clad cops -- their clumsy attempt at orderliness is like an affront to his howling, wordless grief.

As Penn plays him, Jimmy looks like a pretty hard guy -- his eyes are small and lost, confused about how they should be relating to the rest of his face, let alone the world -- but we also see how his grief makes him softer. Dave and Jimmy haven't been friends for years, but when Dave shows up at Jimmy's house after the body is discovered, as part of the wave of friends who descend on the family as a show of support, they suddenly find themselves alone together on the back porch. Jimmy reaches out to Dave, without even knowing he's reaching out; his mere acknowledgment of Dave is an act of desperation and kindness, since Dave seems to drift through life in the neighborhood like a ghost, a specter whose presence the locals tolerate but pretend not to notice. Jimmy wouldn't be the sort of guy to say, "Thanks for being here." Instead he compliments Dave by mentioning Dave's wife, who has come to the house to help out: "That Celeste, she's a godsend, thank her for me, will you?" Penn says the words casually, as if they were just chitchat, but their meaning is clear: Our only real hope of communicating man-to-man is to go through our women.

Later, we see that Jimmy's grief hasn't softened him at all. Instead, he has a way of turning sorrow into extra muscle -- it makes him stronger and more lethal, as well as more unreasonable, than he ever was before. And yet we can't turn away from Jimmy: When he asks the funeral director if he can see his daughter, he's led to a basement, where he looks down on her body. He's brought a dress for her to wear, and he lays it on top of her sheet-covered body as if she were a paper doll. His tenderness becomes inextricable from his monstrousness. This is one of Penn's most complex performances, and it may be his greatest.

"Mystic River" is a man's movie, and that's not a slam: For one thing, it's anchored by a tripod of great male roles, ones that give the actors who fill them something to work with. Moviegoers and critics often assert, and not incorrectly, that there aren't many good roles for actresses of middle age and above. But it's not as if opportunities to do Chekhov or Shakespeare or O'Neill are lurking around every corner for middle-aged men, either. Watching the three leads in "Mystic River," you realize that Eastwood has done something smart and generous just by handing them these meaty roles.

Its potent masculinity aside, though, "Mystic River" may be Eastwood's most tender movie. When Sean and Whitey (Fishburne) discover Katie's body, the crime scene isn't shown to us with clinical coldness, the way we see it on most TV cop shows. Eastwood wrote the movie's score, and the music he uses in this scene is mournful but restrained -- he's smart enough to keep it from competing with the images, something more seasoned composers have yet to learn (and something plenty of directors never learn). The camera pulls back to show us the lifeless body in its new setting, a tangle of grass and leaves ringed by stones. In just a few short hours, it has become part of the landscape, more at home with the cool stillness of greenery and twigs than with the warmth of human beings.

If that's not empathy, what is? "Mystic River" isn't a perfect movie; there are places where Eastwood's slavish devotion to craftsmanship calls attention to itself, jostling us out of the pure feeling of the story. But we can always find our way back in, which testifies to the movie's effectiveness. This is filmmaking with a strong sense of place and of people: "Mystic River" suggests that where we come from determines, in a notion of fate derived straight out of Greek tragedy by way of film noir, what kind of people we're going to be. But beyond that, the neighborhood's promise of consistency and security means nothing. In noir neighborhoods, as well as the old tragic Greek ones, there's heartache around every corner, for the strong as well as the weak.

Shares