Christine Jeffs' "Sylvia" is a not-very-good movie about a fascinating and underexplored subject: the unknowability of a marriage. You wouldn't necessarily know that from the title: "Sylvia" is ostensibly about the life of the troubled poet Sylvia Plath, who committed suicide in 1963, not long after her husband, the poet Ted Hughes, left her and their two children for another woman.

Since then, Plath has been seized as a feminist icon, a feral but sensitive creature who was misunderstood by the world and thus doomed to an early death. And because behind every doomed woman there's an oppressive man, Hughes has made a conveniently shaped puzzle-piece villain in the Plath legend. He's Mr. Rochester transplanted to "Gaslight." You couldn't custom-die-cut a better bad guy: Forget the layers of evidence that Plath's death devastated Hughes and haunted him for the rest of his days -- if it's at all possible to take the full measure of heartbreak in a paper trail of anguished letters, not to mention actual poems. A British poet laureate, Hughes died in 1998, very shortly after publishing a book of revelatory and astonishing poems about Plath, "The Birthday Letters" -- as if the intimacy of revealing so many details about his feelings for her were too much for him to bear in life.

Hughes also, famously, burned some of Plath's journals after her death, claiming that he wanted to shield his and Plath's children from the pain of reading them. To Plath's protectors, that was obviously a case of a guilty perp destroying evidence or, worse yet, history: To these keepers of the flame, literature was deemed more important than life. No one save Hughes knows what was in those journals. (If Plath was distressed enough to take her own life, who knows what she may have written about her young children shortly before her death? Many mothers complain about how their toddlers exhaust and frustrate them, but most of them, thank God, don't commit suicide with those children in the next room.) But apparently, the instant Plath died, those journals became the rightful property of the world of letters; Hughes, hoping to protect his motherless children, his own privacy and possibly his dead wife's reputation, wrecked the fun for hundreds of gossip-hungry literary sleuths everywhere.

"Sylvia" doesn't take us that deep into the controversy -- it ends with Plath's death, just after she has placed a tidy trayful of bread and milk in the room where her two children sleep, sealed off that room and retreated to the kitchen, where she then turns on the gas. But I think "Sylvia" is an indirect response to that controversy -- and one that's not so much sympathetic to Hughes (although it is that) as it is sensitive to the mysterious and unplumbable depths of coupledom. For all its problems as a movie, "Sylvia" at least strives to make the point that the only two people who can know what goes on in a marriage are the people who are actually in it. Biographers and literary critics (as well as, of course, filmmakers), no matter how many mossy stones they turn over, can never know the truth of it.

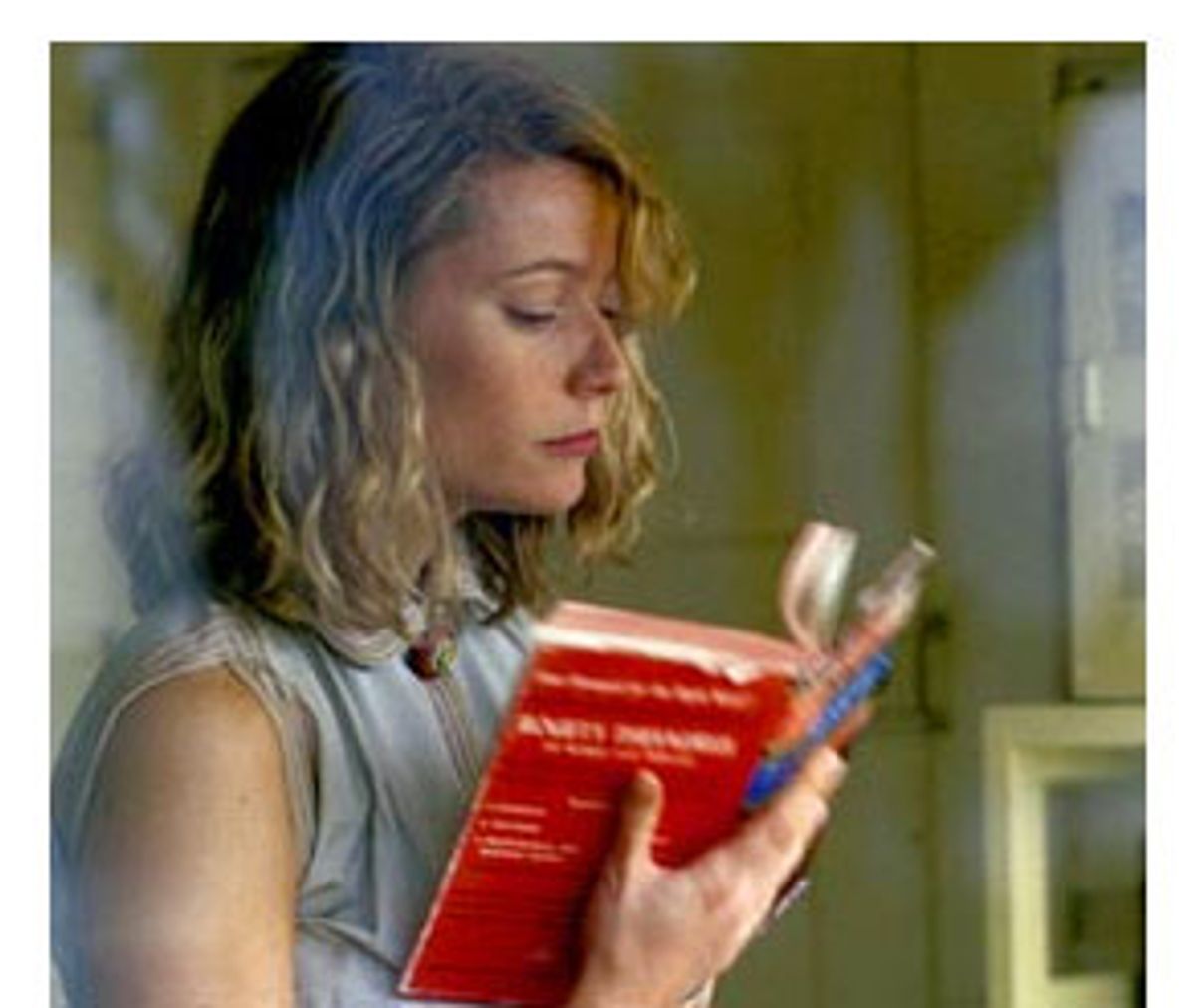

Gwyneth Paltrow plays Plath, and when we first see her, she's wheeling down an English street on her bicycle, wearing a peach-pink twin set, her schoolgirl's skirt rippling like a flag around her. She looks buoyant and athletic and not at all tortured: It's 1956, and Plath is attending Cambridge University on a Fulbright scholarship. We see Plath reading a poem by a young man she doesn't yet know -- Hughes -- and we see how much it moves her. Not long after, she locates Hughes at a party (he's played by Daniel Craig, whose virile, handsome mug and swag of dark hair instantly mark him as a classic Mr. Danger). The movie makes it clear that Plath is his match -- his equal -- from the start. She strides toward him, reciting one of his own poems, a bald assertion that she's choosing him and not the other way around. They talk for a moment but have to break apart quickly, lest Hughes' jealous girlfriend spot him looking so clearly mesmerized. When he moves in as if to kiss her, she bites him on the cheek; he swipes one of her earrings. Let the games begin.

Hughes and Plath have what is clearly great sex and marry within four months. She brings him home to New England to meet her chilly, controlling mother (played with icy, tremulous precision by Paltrow's real-life mother, Blythe Danner), who's wary of Hughes and not wholly approving. The couple embark on a life together, eager to support and encourage each other's work, although Plath has some trouble settling down to it: The two spend some time on the New England coast, where Plath is supposed to be writing; Hughes returns home from an afternoon of fishing to see that she's baked pies and cakes instead of writing poems, and registers his disapproval, which makes her sullen and sulky.

The trouble in paradise brews slowly at first, and then starts roaring: Hughes is a more successful and more famous poet than Plath is -- he entertains his many followers, many of them attractive and female, while she holds down a drab teaching position. Her jealousies, both sexual and professional, begin to eat away at both her and the union itself. The couple decide to return to England, where their problems only intensify. Plath, who has meanwhile given birth to two children, sees sexual rivals everywhere and accuses Hughes of any number of transgressions. Before long, the movie suggests, she has practically browbeaten him into an affair with a dark, exotic creature named Assia, the woman who will eventually become his second wife.

"Sylvia" seesaws in its point of view, showing one partner's side and then contrasting it with the other's. Plath seethes with jealousy after spotting Hughes with a pretty student, and calls him on what she perceives as his unfaithfulness, to which he replies that if he does start sleeping with students, she'll be the first to know. In a later scene, after endless rounds of similar accusations, he slams her roughly against a wall and slaps her face. Later still, after the Hugheses have left their cramped London flat and moved to a house in Devon, we see her serving dinner to Assia and her husband, who have come to the house for a visit.

The movie doesn't tell us whether Hughes is already sleeping with Assia, but if the affair has already started, it seems nascent. Plath suspects something is up, though, and she says barely a word to the two guests, snapping when the poor husband asks meekly if they might listen to the new Robert Lowell recording after dinner. With untethered hostility, Plath grabs Assia's soup plate before she's finished eating and proceeds to murderously slice her a piece of pie. Hughes takes her aside to speak with her, and she lashes out at him, asserting that she will not be humiliated. "Nobody's humiliating you," he hisses back. "You do such a bloody good job of that yourself."

In other words, Jeffs and screenwriter John Brownlow haven't bought into anything as simple, or as boring, as the myth of St. Sylvia, the poor, put-upon wife victimized by the bearish thug of a husband. As she's written, and as Paltrow plays her, this Plath is both vulnerable and unbearable. But instead of letting her coast by on the genius train, Jeffs and Brownlow call Plath on her bad behavior. It makes her story more affecting, rather than less: At one point, after he's left Sylvia, Hughes confesses to the couple's mutual friend, the critic Al Alvarez (Jared Harris), "I can't go back to her, but I love her so much." His voice is restrained and yet striated with millions of imperceptible cracks; the movie presents his break from her as a kind of self-preservation, but it acknowledges the huge price he paid in doing so.

Paltrow makes for a reasonably convincing Plath: She's such an openhearted actress that you immediately believe in her vulnerability, if not necessarily her brilliance. But there are places where she has to utter lines -- many of them things actually said or written by Plath -- that make her character so tiresome and self-absorbed that you wonder why you should be interested in the first place. In "Sylvia," Plath always chooses what would otherwise be pleasant or at least profoundly intimate moments between herself and Hughes to swing her big sack o' woe down with a thunk. Just after she and Hughes have made love, and lie in bed entwined in each other's shadows, she intones, "I tried to kill myself three years ago." Not much later, when the two find themselves in a rowboat on a patch of rough New England ocean and Hughes expresses fear that he might not be able to get the boat back to shore, she announces darkly, "I tried to drown myself once."

Although they're played to be dead serious (and there's little doubt that in real life, Plath suffered from serious clinical depression, at the very least), these assertions start to seem comical, like a Carol Burnett movie parody in which a character announces her impending death with a meek, feeble cough. "I was dead, but I rose up again like Lazarus," Paltrow's Plath tells Hughes cheerfully and firmly, but we know that the line is really a dry run for one of the poems that would appear in Plath's final book, the 1965 "Ariel," which cemented her literary reputation. "Lady Lazarus, that's me," she says. Even if Plath did say such a thing in real life, in the movie it feels like just another kind of corny foreshadowing.

Ultimately, "Sylvia" is too full of moments like that. Jeffs -- whose previous feature was a nicely observed coming-of-age movie called "Rain" -- takes great care to show us Hughes' and Plath's suffering, together and apart, and to make it clear that Plath couldn't have been easy to live with. And yet the fact that Jeffs is so respectful of the Hughes-Plath union presents its own set of troubles. Just how do you put a marriage on-screen respectfully, but also in a way that illuminates something about the characters involved in it? "Sylvia" was shot with extreme care, perhaps too much care, by John Toon: We're treated to lots of quietly shuffling golden autumn leaves, glinting tragically in the sunlight, another classic portent of early death.

Jeffs is ultimately undone by the "We love each other so much that we can't stand each other" subtext of the Plath-Hughes story; its melodrama is what attracts us as an audience in the first place, but in her painstaking efforts to avoid prurience, Jeffs makes it all a little bit too tasteful. "Sylvia" often feels like a Lifetime made-for-TV movie, a seemingly modern yet weirdly retrograde version of the type of doomed-romance weeper that some imaginary stay-at-home mom might turn on in her last two hours of peace before the kids come clattering home from school.

It's a little surprising that "Sylvia" is so conventional, considering that Plath, whatever you think of her work or her life story, openly defied plenty of the '50s conventions. I don't think Plath should be canonized for that, just as I don't think she should be canonized merely for the fact that she suffered, or was "difficult." But what kind of woman bites a man on the cheek when she first meets him? That's the Sylvia Plath I find most compelling, the one who had an appetite for life, at least in the small windows of time while she wasn't obsessing about death.

Sylvia Plath is a fascinating character but a lousy icon. I don't happen to care much for her poetry: Where others see passion, I see carping; her version of hard-bitten introspection reads like extreme self-pity to me. Would I feel differently if Plath's short and tragic life -- and Hughes' life along with it -- hadn't been hijacked by any number of book-benumbed thinking-cap types who drive agendas as if they were glamorous, racy little red sports cars? Probably. But I can't change the way Plath's legacy has been appropriated any more than I can change the specifics of her life.

At least "Sylvia" has the good grace to reject using the lives of real people, entwined in a real marriage, to tick off easy points about either sexual or literary politics. It puts Hughes and Plath behind the wheel of their own destinies, suggesting that before they became one of the most famous (or most infamous) couples of 20th century literature, before either of them became symbol or signifier, they were flesh and blood. And they knew each other much better than any of us ever can.

Shares