Have movie and TV audiences become desensitized to the brutality and murder of women on-screen? If so, Jane Campion has the solution: Render grisly sex crimes in the dullest manner imaginable. After all, if we're indifferent to blurry pictures of mutilated corpses and severed heads, we sure aren't going to be titillated.

Campion's adaptation of Susanna Moore's serial-killer literary-fiction exercise "In the Cut" feels less like a movie than a gallery installation: It's dopily static except when Campion wants to make one of her world-famous, patented, serious-thought-provoking points -- then she jabs the picture as if with tiny electrodes, jolting us to make sure we're awake enough to catch the message. In this case, Campion -- as she did in that earlier head-thumper of a picture, "The Piano" -- has some very important feminist dialogue to attend to: She wants us to know that women's dreamy expectations of true love, commitment, marriage and security stand in direct opposition to the harsh reality of life.

Remember the old statistic that struck horror in the hearts of single women everywhere -- that bit of business about a woman having a better chance of getting blown up by a terrorist than getting married after the age of 40, or whatever it was? Long after that statistic was proved false (although what was truly shocking about it was that it wasn't laughed off the table, regardless of its veracity, in the first place), Campion is still beating her wooden spoon on the back of the pot. Women dream! Women want! Women's expectations are dashed! she intones. Somewhere in there, a few bodies get chopped up by a killer madman, which probably counts as a dashed expectation, and if you ask me, it's right up there with waiting fruitlessly for the phone to ring, washing dishes and changing dirty diapers. Heck, it might even be worse.

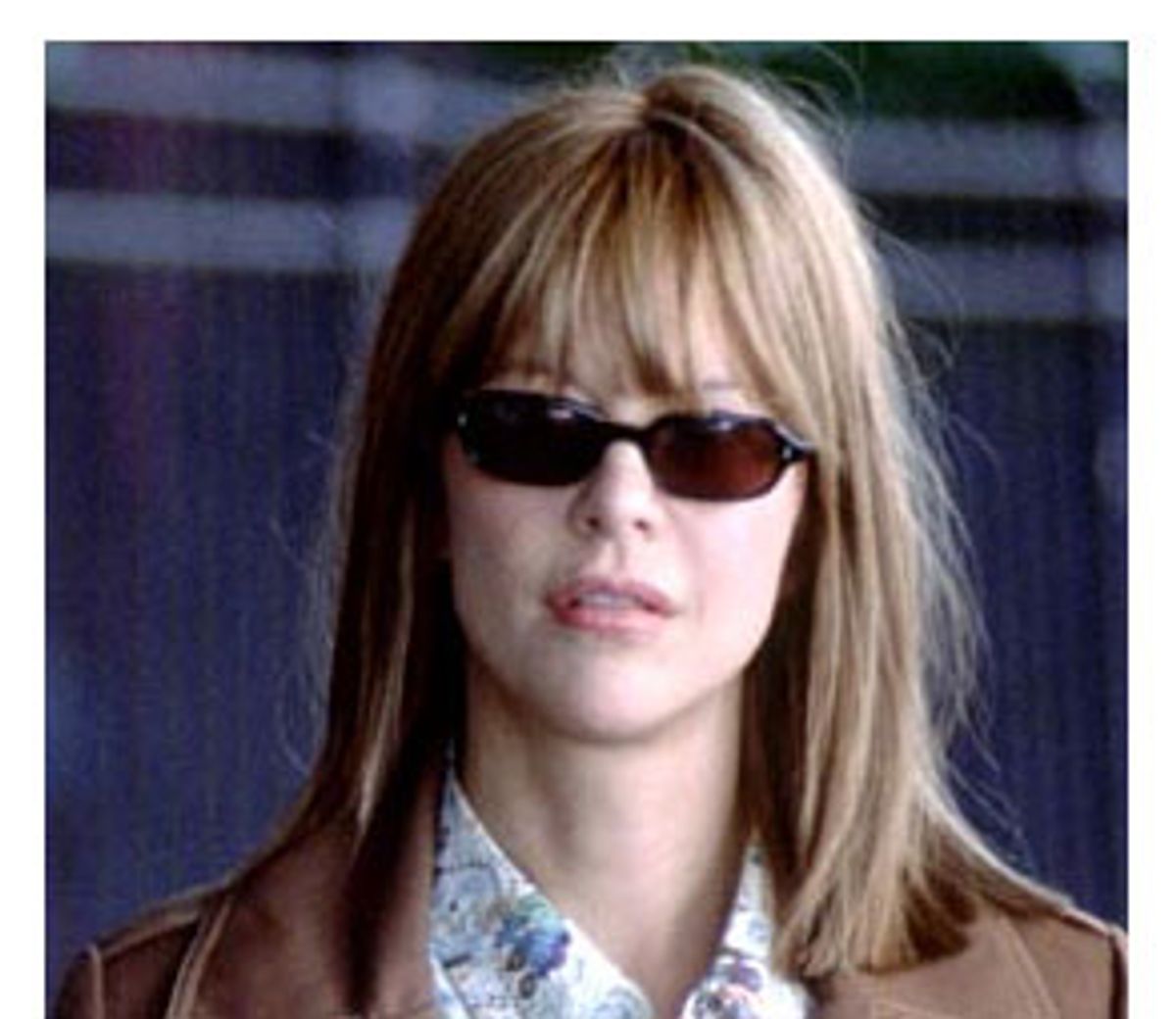

What, exactly, does Campion -- who both directed and adapted the screenplay -- mean to say with "In the Cut"? I'm not entirely sure, but I do know that I laughed more than once at poor Meg Ryan as Frannie, the mild-mannered and sexually bashful New York schoolteacher who becomes entangled in a serial-murder case being investigated by Detective James Malloy, a boorish hunka man who strides purposefully through the movie in the form of Mark Ruffalo. Frannie loves poetry. No, let me put that more succinctly: She's a poetry nut. She hearts poetry, and we know this because when she rides the subway -- and being a schoolteacher of little means, she rides it a lot -- she makes it a point to read the poems that grace the placards adorning some of the subway cars. Her face becomes transfixed as if she's seen a beatific vision; she murmurs the words as she reads them, committing them to memory, sometimes jotting them down on a piece of paper lest their power slip through her grasp forever. Oh, the dreams of the little people! Just a little poetry is all we ask! Instead, we get our heads chopped off. There is surely something wrong with this world we live in, and Campion is here to tell us about it.

Frannie can't resist the allure of Malloy, who courts her by shoving ugly crime-scene photos under her nose, one of which, a picture of a severed head, might be horrifying if it didn't look so much like one of those el-cheapo beauty-school dummies with flyaway synthetic hair. Later, he takes her out to a bar and makes crude remarks about the kind of sex he'd like to have with her; later still, he makes good on his filthy promises, and it turns out Frannie really likes it.

But she has her doubts about this Malloy, even though her sister, Pauline (Jennifer Jason Leigh), urges her to at least have some fun for a change. Pauline, you see, is a sexual free spirit, which means that she's doomed to be shown from camera angles that fixate on the pierogi-shaped roll of flesh under her chin, on the saggy pillows of her breasts confined beneath her too-tight tops. ("In the Cut" was shot by Dion Beebe, the gifted cinematographer behind "Charlotte Gray" and "Chicago," but his clean, precise images come off as calculated and sanitized here.) Pauline speaks in a dreary whine that suggests -- let's just whisper it, now -- "low-class." Frannie, on the other hand, favors neat little Marc Jacobs tops with trench coats and flat shoes -- as if the mere fact that a woman doesn't invite sex automatically makes her more deserving of it, while a woman who dresses like a floozy is invited to be the object of our pity.

But just like Frannie, poor Pauline has dreams, and Campion, without breaking her condescending stride, lets us know what they are. Pauline is in love with a married doctor; she's been caught out by his wife. Still, she does dewy-eyed, stalkerish things like pick up the doctor's dry-cleaning; then, after the fact, she giggles about it like a deranged tootsie, wondering aloud why she'd do such a thing. She wants love and marriage, you see. She gives Frannie a charm bracelet with marriage- and baby-related trinkets dangling from it; when Frannie holds the bracelet up to examine it, its tiny baby bassinet and miniature honeymoon cottage sparkle before our eyes like the bullet points on a college term paper.

Not even Meg Ryan, who has built a career playing cute snuggle-bugs, deserves this kind of treatment. In fact, there are places where Ryan is surprisingly touching: She takes her role so seriously that she makes us feel something for Frannie, even though Campion seems mostly interested in turning her into a symbol.

Campion is supposed to be a woman's director, whatever that means. So when Malloy drives Frannie down a deserted, wooded road to a body of water dotted with dead branches and floating garbage bags, why does Frannie turn to face this grungy scene and begin to recite, in milky, half-awake tones, John Keats' "La Belle Dame Sans Merci"? In other words, what kind of director allows -- or, worse yet, asks -- one of her actors to come off as a complete nincompoop? I struggled with "In the Cut," not because its themes were so complex, or because its images were so artful or so disturbing, but because I wondered how a movie made by an ostensibly thinking person (though I think saying even that much gives Campion way too much credit) could leave me feeling so totally lobotomized. I don't care so much that the movie's ending is implausible, or about the fact that Frannie is a New Yorker who doesn't think twice about getting into a vehicle with people she barely knows (if you're going to talk about the dangers women face in the big bad world out there, you should at least acknowledge that cultivating a bit of common sense doesn't hurt, but never mind). "In the Cut" isn't just a movie about decapitation; it's a decapitated movie. It has no idea where its head is at.

Shares