"Saturday Night Fever," which was essentially a very old-fashioned story about making it in the big city, should have accustomed us to seeing old movie-musical conventions side by side with contemporary pop music. Still it takes a while to get used to the rags-to-riches tropes in the new hip-hop musical "Honey." The young audience that will want to see "Honey" probably won't even register the hoary clichés, not having seen the pictures "Honey" makes reference to. Older audiences may feel like the director, Bille Woodruff, and the screenwriters, Alonzo Brown and Kim Watson, have spent a lot of time watching "Gold Diggers of 1933" or "42nd Street."

Not that "Honey" belongs in the same league as those pictures. There's an entertainingly ludicrous movie lurking somewhere inside of the ludicrous, mediocre one this actually is. Jessica Alba plays a Bronx dancer with the Bond-girl name of Honey Daniels. Honey hustles to make money working at a record store and bartending at a dance club so she's free to pursue her real love, teaching hip-hop dance at the community center run by her mother (Lonette McKee, whose tense, disapproving presence seems to have wandered in from a more serious movie).

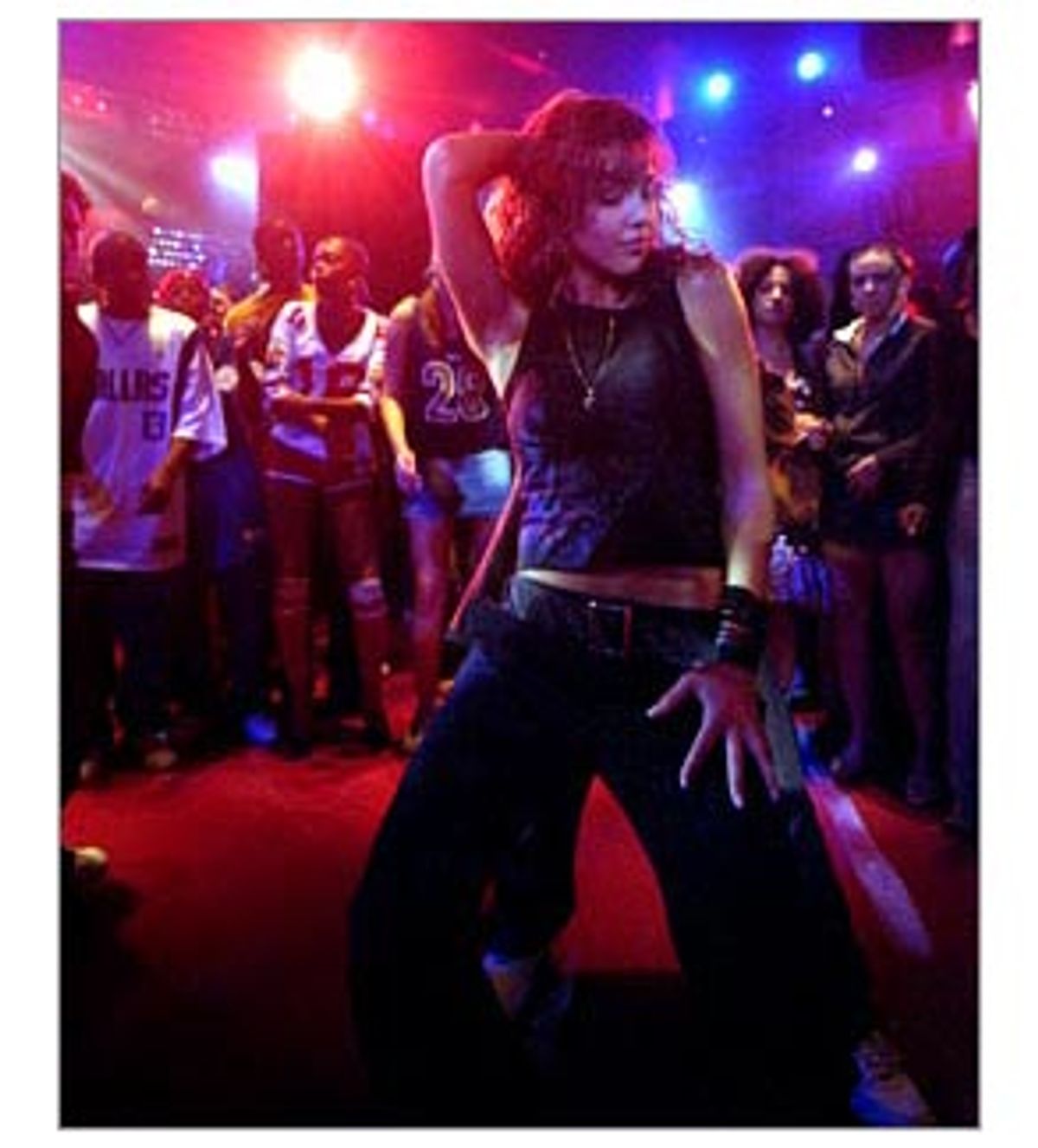

Honey is sighted dancing in a downtown club (the movie's equivalent of the soda fountain at Schwab's) by a hotshot music-video director (David Moscow), whose "down" white-boy persona tells you he's full of shit the first time you lay eyes on him. She progresses quickly from background dancer to choreographer, encountering all the predictable clichés about the old friends who feel success has made Honey neglect them. But the biggest cliché still lies in wait: Honey will have to choose between her burgeoning career and the troubled street kids she's trying to save.

If Woodruff, Brown and Watson had energized the hackneyed devices and strengthened the movie's dramatic structure, "Honey" might have had some oomph that would have carried you right over the predictability. Instead they introduce conflicts -- the harassed, hostile mother of the neglected kids Honey is mentoring; her troubles with her own mother, who wants her to become a ballet dancer -- and then, in the finale, suddenly resolve them without dramatizing any resolution.

It would be nice to think that the movie's implicit criticisms of hip-hop culture bling-bling are the result of the filmmakers' subtlety rather than their laziness. But they suggest fleeting notions rather than a considered statement. Honey's first appearances in music videos for Jadakiss (one of the artists who appear as themselves) and others make her little more than a glorified cooch dancer. The movie appears to be attempting a statement on the crassness of some hip-hop video. But though the bump-and-grind is noticeably less in the dances Honey choreographs herself, what we see isn't distinctive -- you simply can't believe she'd make as big a splash in the world of hip-hop video as she does. (Alba doesn't make nearly the impact that Jennifer Lopez does aping Jennifer Beals in the "Flashdance"-inspired video for "I'm Glad.")

Woodruff, a video director himself making his feature debut, has no particular talent for shooting dance numbers. He doesn't let us see the dancers' bodies, and his cutting doesn't jibe with their performance rhythms. In a later section, Honey succeeds in getting the kids she teaches cast in a Ginuwine video. But that white director, whose advances Honey has spurned, scotches the concept in revenge and Ginuwine goes along with it. It's a horribly melodramatic concept, relying as it does on the crushed dreams of disappointed kids. But you can't help wishing the filmmakers had been canny enough to turn it into a question of how pop music stars let down their fans, sometimes by holding up a lifestyle their fans can't hope to emulate.

It's probably asking too much for a featherbrained picture like "Honey" to address those issues. But since it raises them, there's no choice but to judge how well it follows through. And if you've heard "Wake Up," Missy Elliott's new duet with Jay-Z that does address some of the things "Honey" raises, the movie's floundering stabs at an examination of hip-hop culture evaporate.

What makes "Honey" painless to sit through is probably a matter of timing. At a season when nearly every big studio release wants to hit you over the head and prove its award-worthiness, a no-big-deal entertainment like this one can feel like a little reprieve. Alba is a strange mix -- she's dewy fresh, but her lewd, glossy lips suggest something a little porny. At times she looks like a chipper version of Reiko Aylesworth from the Fox series "24," though with the personality wiped out. For most of the movie, Alba's midriff gives more of a performance than the rest of her. It's probably the most active movie midriff since Ray Walston waggled that tattoo of a ship in "South Pacific."

Mekhi Phifer, as the barber who woos Honey, has next to nothing to do, but his casualness goes down easy. As Benny, the street kid hovering on the verge of a life of crime, Lil' Romeo brings a standard role more authenticity and conviction than it probably deserves. Joy Bryant, as Honey's best girlfriend Gina, is a long-limbed delight. She's basically playing the sassy black girl, but the more I saw of her the more I liked her (and Woodruff should have included a few more scenes of Bryant wearing her glasses -- in specs, she's a knockout).

Best of all is Missy Elliott, who shows up as herself in two scenes and reduces the audience to happy pandemonium. I don't know when I've seen a performer get so much out of a few simple reaction shots, but she times her reactions -- and the choice wisecracks she's given -- so perfectly that you can't believe moviemakers won't be scrambling to give her a full-fledged role.

If there's a reason to care about a trifle like "Honey" it has to do with the future of movie musicals. "Chicago" proved that great movie musicals were still possible, but the genre isn't going to flourish if what we've got to look forward to is Joel Schumacher's "Phantom of the Opera" (flee while you still can!). The future of the musical will depend on filmmakers who can find a way to translate contemporary pop (which right now means hip-hop, R&B and dance music) into the form. It's going to take more than video directors and studio execs banking on getting kids into the theater with the promise of hip-hop stars and a heavily promoted soundtrack album.

"Honey" suggests that the old stories of realizing your dreams, even as baldly retreaded as they are here, may still have some life for audiences. But the predominance of black music right now deserves better. It would be a shame if Hollywood blew the chance to make audiences as excited about what they see on-screen as what they hear on the radio.

Shares