The four men speak flawless Arabic. Their vocabulary is extensive, their grammar precise. From their mouths come sounds that could only come from a native speaker -- H's that linger in the back of the throat, R's from somewhere underneath the tip of the tongue, and several letters that don't even exist in other languages.

No matter what they say, every word they speak shouts it over and over again: "I am an Arab."

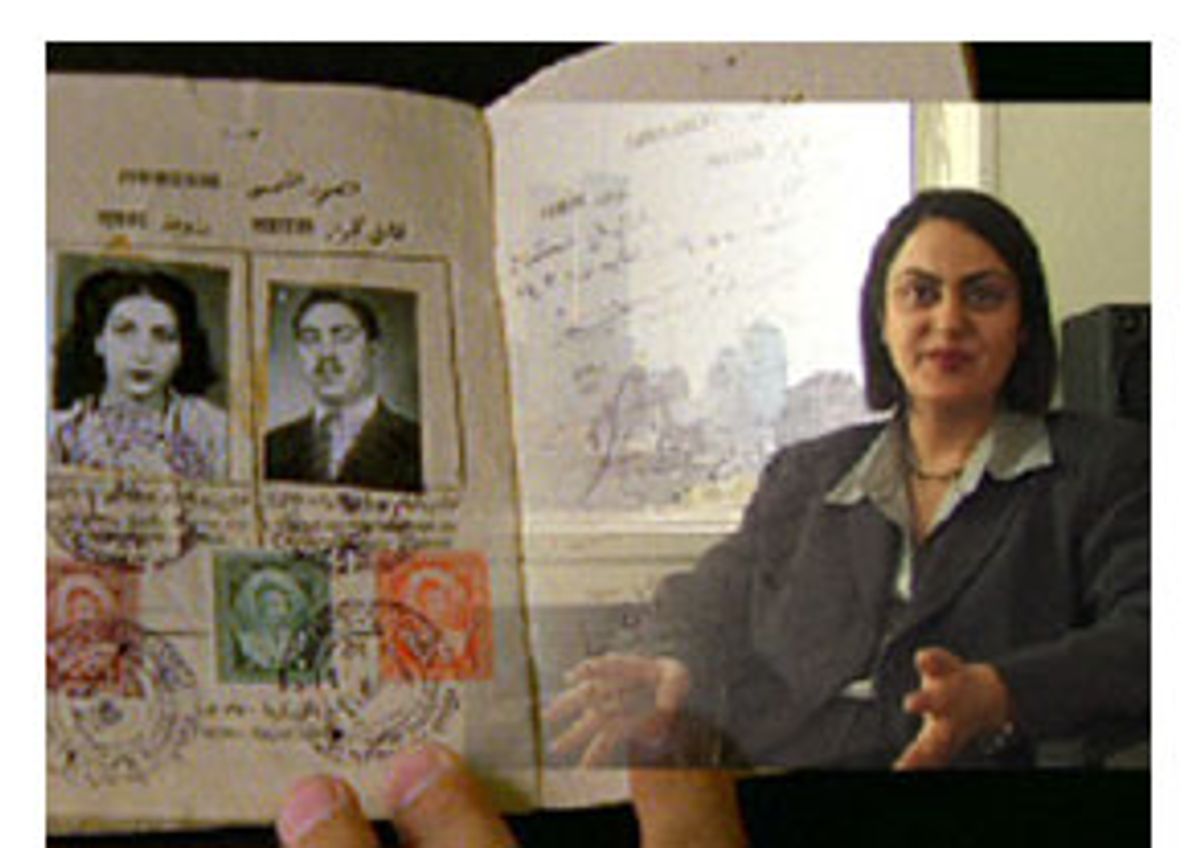

Pictures from their childhoods flash across the screen, photos of parents, aunts, uncles, brothers and sisters. Their relatives' hair is black and thick, their skin the color of olives, their eyes as brown as well-oiled wood. The men and their families would blend in perfectly in any marketplace in Cairo or Beirut -- or even Baghdad.

In fact, just 50 years ago, they did. Each of the men is not an Arab, but a Jew. Or, if you were to ask them, both Arab and Jew at the same time. Iraqi and Israeli, all at once. The former country is their homeland, the latter country their home, or the closest thing to it.

This seeming paradox of identity is exactly what drew the documentary filmmaker Samir to the stories of these Arab-Jewish-Iraqi-Israelis in his film, "Forget Baghdad," now playing at the Cinema Village in New York and scheduled for a January opening in Los Angeles, Chicago and San Francisco.

Samir, a Shiite Muslim born in Baghdad but raised a continent away in Switzerland, understood personally the dissonance of living with two conflicting cultures at once. He grew up listening to his father's stories about his Jewish comrades in the Iraqi Communist Party, comrades who had moved to Israel soon after its founding in 1948.

Samir flew to Israel in 2001 to find them. Although he couldn't locate any of his father's old friends, he found four other former Iraqi communists: Shimon Ballas, an author who now writes in Hebrew; Samir Naqqash, a novelist who only writes in Arabic; Moshe (or Moussa, in Arabic) Houri, a retired kiosk owner; and Sami Michael, a bestselling Hebrew author. For a younger perspective, Samir also spoke with renowned Israeli film scholar and cultural critic Ella Shohat, an Iraqi Jew born in Israel whose book "Israeli Cinema: East/West and the Politics of Representation" caused an uproar upon its publication in Israel in 1989.

"I wanted to know what it's like to change countries," Samir says at the beginning of his film. "To forget your cultures and your language, to become the enemy of your own past."

What he unearths is a haunting collection of memories and attachments that have not and could never be truly forgotten, that eerily transport us back to the past -- through a mix of black-and-white photographs and grainy newsreels -- even as they pull us toward the present and the ongoing struggle in Iraq that continues to dominate our national consciousness.

Of course, when Samir began production nearly three years ago, there was no way for him to know how topical, how present-tense, "Forget Baghdad" would seem upon its American release.

Even then, challenging the boundaries between East and West was an inherently subversive act. It hadn't been very long since the end of the Gulf War, and the American popular media had already made a habit of portraying Arabs and Muslims as terrorists, reserving the role of hero for blond-haired, blue-eyed Euro types. (Check out Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger's "True Lies" for one of the most blatant and despicable examples.)

For its part, Israeli society had long consisted of a dominant Jewish minority -- Ashkenazi Jews who emigrated from Europe -- and a repressed majority of Mizrahi or Sephardic Jews who originated in the Middle East. Even at the start of the 21st century, mainstream Israeli society had only recently begun to address its endemic racism against Mizrahim.

But in today's post-9/11 world, with a new American war in Iraq far from over, and with no end in sight to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, "Forget Baghdad" will prove even more memorable. By exploring the deep and lasting bonds between Iraqi Jews who are now Israelis and their former homeland, Samir blurs the lines between good guy and bad guy, "us" and "them," questioning the typically unquestioned nationalism that drives the worldview of George W. Bush's America and Ariel Sharon's Israel alike.

To listen to popular discourse on Iraq -- from Washington's official line to the words of our papers' most liberal columnists -- you would think the Iraqi people are virtual savages, a culture totally removed from the modern world and incapable of fathoming its sophisticated political structures. "We'd love to give them democracy, but how?" is the explicit message. Implicitly, such commentators seem to be arguing that Iraqis are too stupid to know what is good for them.

But Samir and the people he interviews paint a completely different picture of Iraq and Baghdad. Their Baghdad was the capital of Arab intellectualism; Houri, an educated man, fondly recalls being embarrassed at a small party meeting by a cobbler who was much better acquainted with the intricacies of Marxist theory. Their Baghdad was a cosmopolitan city, where Muslims, Christians and Jews studied, lived, and worked together; half a century ago, Baghdad's population was 40 percent Jewish.

When the four aging Israelis speak of Iraq, or the beautiful Tigris River that snakes through its capital city, the lines in their faces, at the corners of their eyes and mouths, crinkle in happiness, with joy and love.

To Samir's credit, though, he doesn't overlook the problems Jews experienced in Iraq: occasional discrimination, and even a series of Nazi-inspired pogroms that took place during World War II. Today, Arab propagandists who blindly attack Israel love to talk about how great Jews had it in the Middle East before Israel's creation, but typically forget to mention the drawbacks of minority life.

Despite these negatives, though, none of the film's protagonists were Zionists. The Zionist movement, in fact, had only a small following in Baghdad's Jewish community, whose roots in Iraq extended back 800 years. Even after Israel was founded in 1948, most Iraqi Jews refused to leave their homes -- until a series of bombings at synagogues in 1950 scared them away. To this day, though, as Samir points out, most Iraqi Jews believe the bombings to be the result of a conspiracy between the Iraqi and Israeli governments, both of which would profit by the flight of the Jewish community to its new state.

Yet for Ballas, Houri, Michael and Naqqash -- and many of their Iraqi compatriots -- Israel did not feel like home, and certainly not the refuge they were told it would be. A society founded by Europeans who often treated them like ignorant savages, spraying them with DDT to "disinfect" them upon arrival, made the transition from Iraq to Israel all the more difficult.

Eventually but uneasily, Ballas, Houri and Michael made Israel their own. They found work, married, had children and grandchildren, learned to speak and write fluent Hebrew. But the separation from the past was never final. Houri created his own version of Iraq in a heavily Mizrahi town in Israel. Michael continues to have nightmares to this day -- nightmares about lounging happily in Baghdad, until his Arab friends find Israeli money in his pockets. And then there's Naqqash, who has never stopped writing his books in Arabic and has never truly accepted Israel as his own nation.

This kind of narrative threatens official Israeli historiography, which likes to portray Israel as the monolithic savior of the Jewish people. Particularly at a time like now, when in the face of the ongoing Palestinian uprising, a strict battle cry of "Arab vs. Jew" has become expedient for the Israeli government and its most devoted supporters.

Even with all of these powerful ideas, the film is much more than a purely intellectual exercise. It succeeds in making strong political points only because it so deftly succeeds in bringing the stories of each character to life, making their longing for lost homes and lost times so tangible.

During each interview, half the frame is used for the subject while half is devoted at times to family photos, at times to fresh footage of Iraq and Israel, and at times to old newsreels showing the Iraq and Israel of the 1950s. (You know the kind -- half news, half P.R., featuring footage of happy workers digging ditches while a voice with an English accent says things like, "The air was full of events to come. And come they did!")

As the Israeli-Iraqi Jews speak in Arabic, English subtitles scroll across the bottom of the screen even as subheadings in English, Hebrew and Arabic script flash across the top. Shohat's interview adds another level of dissonance -- it took place in her office at New York University, and the view from the window reveals the ghostly presence of the World Trade Center towers. All this is mixed with a fantastic jumble of selections from pop-culture representations of Arabs, Israelis, Muslims, Christians, Ashkenazi and Mizrahi Jews.

You are simultaneously inundated with Arabic, Hebrew and English, the past, the present and hints of the future, different places, different cultures and times. Trying to take it all in is a jarring experience, almost overwhelming -- just enough to give you the sensation of what it must be like to be them: to be so many things, Arab, Jew, Israeli, Iraqi, friend and enemy, all at the same time.

Shares