If you've ever had a dream in which you're painfully aware of having lost something, or someone, but you have no idea what or who has slipped away from you -- a dream in which an absence is a presence, a cookie-cutter-shaped hole moving like a ghost in the space around you -- you'll understand "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind" intuitively. You may also find it devastating.

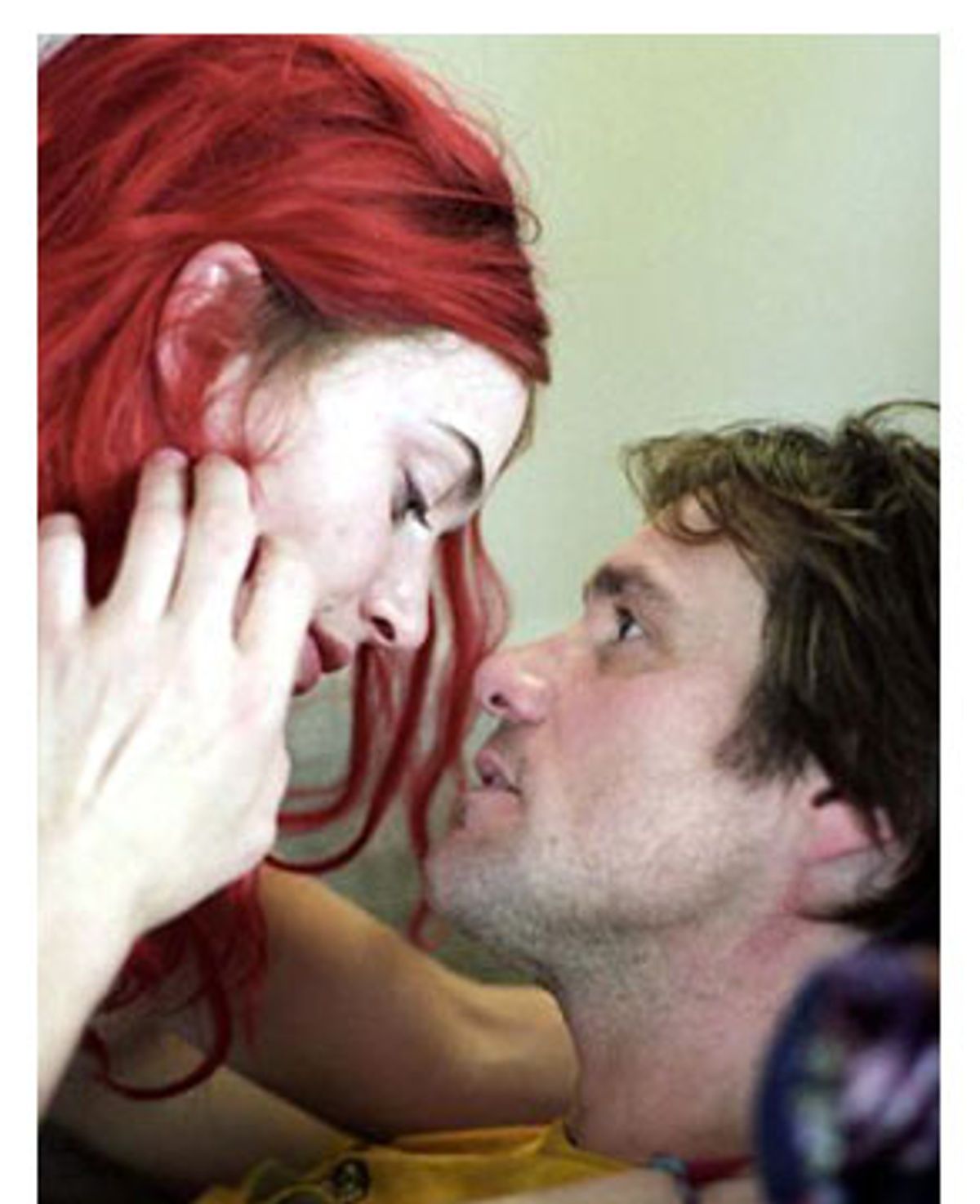

This is French director Michel Gondry's second full-length movie, written by Charlie Kaufman (with whom Gondry also collaborated on his first picture, the 2000 "Human Nature"). In "Eternal Sunshine," Jim Carrey plays Joel, a man who arranges to have every memory of his ex-girlfriend, Clementine (Kate Winslet), erased from his brain, only to realize that those memories may be more dear to him than the failed union itself: They're all he's got left.

The movie traces the romance in reverse-order flashbacks, starting with the most painful memories of the breakup and working forward to the earliest, sweetest ones. Joel realizes that in allowing bits of Clementine to disappear, he's also erasing chunks of himself. "Eternal Sunshine" is a meditation on the way other people go to work on us in ways we're barely aware of, like ghostwriters who grab the pen when we're not looking, writing new chapters for us that are better than any we could have come up with on our own.

The best moments of "Eternal Sunshine" are deeply and desperately moving: At times the picture feels achingly alive. In fact, the first 20 minutes or so of "Eternal Sunshine" are so free of gimmickry and self-consciousness that I almost couldn't believe it had been written by Kaufman, who has built a tidy career out of writing cool-weird puzzle movies, brain teasers for modern audiences who might get bored if they were left to do the work of simply confronting their emotions. Was there more to Kaufman than I'd previously given him credit for?

The answer is that, yes, there may be. And yet there's still not quite enough.

"Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind" represents a failure of nerve: As if Gondry and Kaufman weren't sure that the story of Joel and Clementine would hold us, the doomed couple's unfolding-in-reverse romance is intercut with a subplot filled with zany touches, like Mark Ruffalo as a sexy-awkward techno-geek in Nutty Professor glasses, and Kirsten Dunst as a dippy-adorable office assistant who edyercates herself by memorizing quotations from "Bartlett's." (In her most torturously cute moment, she recites from the poem from which the movie takes its title, attributing it to "Pope Alexander.") The ballad of Joel and Clementine is a piercing reverie, gorgeously sun-dappled and at times so wrenching that it's almost painful to watch. But whenever Ruffalo and Dunst -- or any of the movie's other numerous sidekicks, like far-from-mad-scientist Tom Wilkinson, or Elijah Wood as Ruffalo's well-meaning but dimwitted assistant -- appear, the movie jerks us out of our dream state.

You might argue that this is a dramatic device, a way of breaking what would otherwise be an incredibly intense story into easily digestible bits. But I think it's symptomatic of a much larger, thornier problem in moviemaking today, one that undercuts the reasons movies have come to mean so much to us, emotionally and culturally, in the first place: The '90s were all about ironic detachment -- it was uncool to care too much about anything, or at least to admit as much. Now that we've tread somewhat tentatively into the 21st century, most of us claim to have gotten over the irony thing. And yet, many of the movies of the past five years that have been hailed as inventive and interesting by young audiences -- pictures like "Memento," "Being John Malkovich" and "Adaptation," the last two written by Kaufman -- are also movies that work hard to wow us with their jigsaw intricacies.

It's as if young filmmakers fear that their audiences will become bored with a movie if they don't have a clever mind-boggler to wrestle with along the way (the equivalent of a magnetic bingo game on a long car trip). In grappling with these perplexing riddles, we're supposedly exercising our intellect. But isn't it also possible that we're using them as a handy diversion, a way of distancing ourselves from emotions that might be too strong for us to deal with easily? Labyrinthine plots are supposed to stimulate us. But are they really just distracting us from the work at hand -- the work of feeling?

I'm not saying audiences shouldn't take pleasure in intricate movies. It can be exhilarating, and just plain fun, to feel your brain and your imagination working in tandem, as you do while watching pictures like "The Usual Suspects" or "Femme Fatale" or "The Big Sleep" (the last a movie that doesn't make much sense at the end, although getting there is so much fun that it hardly matters).

But just as there's a difference between knowing things and being informed, there's a difference between going all the way with a movie and going only as far as is convenient or comfortable. One of the most popular features ever run in Salon was a 2001 article called "Everything You Wanted to Know About 'Mulholland Drive,'" a dissection of every explicable or inexplicable mystery of David Lynch's ode to both the gleaming surface and tawdry underbelly of Hollywood. "Mulholland Drive" does work as a puzzle, and its intricacies are enjoyable. Personally, though, I'm much more interested in its hypnotic poetry and the tarnished-tinsel quality of its images. And while it's always fun to ponder Lynchian details, you can miss the point of Lynch's movies entirely if you spend too much energy pondering the significance of the scruffy maniac in the parking lot or the contents of the blue box.

That said, I suspect that whether they recognize it or not, audiences yearn for movies that can make them think and feel. And for many moviegoers, "Eternal Sunshine" may fit the bill. There's so much that's right with the movie that, just a few days after seeing it, I've already done a fairly decent job of blotting out everything I hated about it as I watched it -- we all have our own memory-erasing techniques.

The beginning of "Eternal Sunshine" is nothing short of lovely; in fact, it's close to perfect. We see Carrey's Joel waking up in his plain-vanilla outskirts-of-New York apartment on a shivery winter morning; striding toward his car in the parking lot only to see that the driver's side door has been gouged; waiting on a crowded train platform, headed for his job in the city; and then making a last-minute dash for a train to Montauk, for reasons we won't fully understand till the end of the movie. There he walks along a doleful blue-gray beach. He sees an interesting-looking girl. We hear what he's thinking in a gruff, whispery voiceover that sounds as if it's emerging from the seashell of our own deep subconscious. He asks himself, for example, why he falls in love immediately with anyone who shows him the slightest bit of attention?

On the train back to the city, he gets acquainted with the interesting-looking girl, who is, of course, Clementine. She has blue hair that has further rebelled against authority by sticking out every which way; it will change color several more times during the course of the movie. ("I apply my personality in a paste," she explains to Joel, half apologetically and half defensively.) Their first conversation has a nervous, twitchy energy, animated by their attraction to each other and by their desperate hope that each will find the other amusing and intriguing. (She: "That's the oldest trick in the stalker's book." He: "There's a stalker's book? I've got to read that one.") They speak to each other like people who have just met, after having been lovers for ages.

We want them to be together possibly even more than they do, and Gondry and Kaufman build on that foundation for the rest of "Eternal Sunshine." As the story progresses, we learn that the opening was a flashback of sorts: Joel and Clementine have broken up, bitterly. Joel hopes to win her back by buying her a necklace from her favorite store (in one of the movie's gentlest and most resonating touches, he has chosen a gift that's clearly perfect for her character, a pendant made from a hand-painted shell), but when he shows up at the bookstore where she works, she looks at him as if she doesn't know him. He's crushed, and then angry; before long he finds out that she's had her memories of him erased from her brain, a service offered by a company called Lacuna, which operates out of a city office that looks more briskly efficient than shady.

Joel, in an act of despairing retaliation, decides he wants the procedure done, too. He asks Dr. Howard Mierzwiak (Wilkinson), the doctor-slash-guru who invented the technique, if the erasure carries any risk of brain damage. "Technically, the process is brain damage," Mierzwiak responds with a straight face and a dash of doctorly confidence. The process involves, among other things, knocking the patient out with drugs, placing a helmet on his head that looks like a cross between a colander and an old-fashioned bonnet hairdryer, and attaching a laptop to the whole contraption. A team of trained technicians -- that would be Ruffalo's Stan and Elijah Wood's Patrick -- then locate the pertinent memories on an onscreen map of the patient's brain and zap them one by one.

The unconscious Joel unravels his and Clementine's history, starting with the breakup. But as he moves back through the relationship, surveying all the small moments that make up the mosaic of a relationship, he realizes there are parts of Clementine he can't bear to give up. At one point, the two of them are making love underneath a comforter -- the light shines through it faintly, turning their faces funny colors, and we feel we've been drawn deep inside their tent of intimacy. We see Joel running through hallways of memories, and they're gobbled behind him as if by an invisible crocodile. In one sequence, he and Clementine run past a fence, and its planks disappear one by one, like a disappearing zipper made of piano keys.

The first time Joel hits a memory he knows he can't live without, he pleads, "Oh please, let me hang on to just this one!" The technicians, of course, can't hear him, and they're barely paying attention to their jobs anyway: Stan has invited his girlfriend, Mary (Dunst), over to keep him company. Mary is also the receptionist at Lacuna, and while she takes a fleeting interest in Stan's work, the two of them are much more interested in setting the laptop on autopilot, raiding Joel's refrigerator and liquor cabinet, and stripping down to their underwear and jumping up and down on his bed, barely bothering to avoid his passed-out, helmeted, pajama-clad form. Meanwhile, after having a beer or two, Patrick has taken off completely to spend the evening with his new girlfriend.

"Eternal Sunshine" cuts between that exaggerated, jokey subplot and the real drama of the picture: the desperate efforts of Joel and Clementine, even as they're locked in the confines of Joel's brain, to stick together. (At one point, conspiring to foil the brain-erasers, they hide out in Joel's childhood kitchen: He crouches, in feetie-pajamas, beneath an outsize kitchen table; she has adopted the guise of his childhood baby sitter, in mini-dress and lace-up go-go boots.)

The problem is that the movie stretches too hard to come up with wacky twists and turns, when what's really riveting is the way Joel and Clementine strive to stay connected to one another. The narrative machinations strain at cleverness, but they can't live up to the movie's visual inventiveness, which is so casual and offhanded that it renders this weird fantasy world wholly believable. Gondry built his early career directing commercials and music videos. His work with Björk, in particular, in videos like "Bachelorette," "Human Behaviour" and "Isobel," have an unearthly, quivering quality reminiscent of the early days of filmmaking, the kind of thing Georges Méliès might have done if he were working today. Gondry gave us miniature airplanes sprouting inside light bulbs (before busting out to scatter through the air like insects) and books that start out normal-sized and grow to gigantic proportions.

In "Eternal Sunshine," Gondry's vision is rarely overtly fanciful; he's much more interested in the magic of straightforwardness. (His cinematographer here is Ellen Kuras, and she gives the movie a look of dreamy urgency that's perfect for the story.) The visual effects in "Eternal Sunshine" are stunningly simple: Gondry plays with scale in the kitchen scene, using giant furniture to make Joel seem fragile and tiny. (Gondry has used similar effects in his music videos, and they're also evocative of the effective visual gags Spike Jonze concocted for "Being John Malkovich.") And I have never before seen an everyday quilt lit up with the fragile glow of a Chinese paper lantern. It's the kind of image you drink in and savor, and it's also a metaphor for the connection and warmth that Joel and Clementine have lost. "Eternal Sunshine" is most elegiac when there are no words in sight.

And yet it's to Kaufman's credit that the dialogue between Joel and Clementine always rings true. If you can comb past the craziness around them and just listen to them, you hear that they speak to each other just as people in love (or falling out of it) do. Carrey and Winslet are wonderful here. Clementine is different from any character Winslet has ever played. The actress typically radiates angelic calmness; here, she's always vibrating, an electrified rabbit that can't be turned off. Yet it's impossible not to care for her: Her dippiness isn't an affectation, but a light beam that shines in a wriggly line straight from her soul. She's flaky and feisty in equal measures, a mix of qualities that makes her fragility that much more believable.

Carrey is Winslet's perfect counterpart. Although much of what he does here is funny in a sidelong way, this is a deeply serious, and wondrous, performance. When we finally get around to seeing Joel and Clementine's first meeting, she asks him if she can have a piece of chicken off his plate, and then grabs it before he can say yes. "It was like we were already lovers," Joel reflects, not dreamily but as if he were stating an indisputable fact on which the fate of the nations of the world depended. Winslet is the one with the large, searching eyes, but in my memory of Carrey's performance, his are much larger: They're striving to take everything in, to record events and places but, chiefly, to memorize Clementine's face. It's a face that means the world to him, and it's in danger of disappearing forever. Carrey's Joel is an ordinary guy -- there's something inexplicably touching about his regular-joe shirt-and-sweater outfits -- but his romantic desperation is like something out of a 19th century novel or a '20s silent film. It's large and magnificent, a force that can't help busting out of the framework of everyday life.

Meanwhile, Dunst's Mary and Ruffalo's Stan jump up and down in their underwear, Wood's Patrick bumbles through his newfound romance, and Dr. Mierzwiak's jealous wife shows up unannounced. We're supposed to laugh, or feel nervous apprehension, or wonder what kind of crazy thing is going to happen next -- but all we want to do is get back to Joel and Clementine. Those loopy shenanigans constitute the movie's connective tissue, but it feels stretched out and feeble. What's real and what's not? Kaufman and Gondry seem to be asking again and again, without realizing that the very faces of their two lead actors have completely erased our interest in those types of questions. The filmmakers busy themselves puttering around the boundaries between fantasy and illusion, without realizing that they're the only ones who care: Once we're inside Joel's head, that is our reality.

I've been critical of Kaufman in the past, chiefly because I despised the phoniness of "Adaptation." But if I hold Kaufman responsible for much of what troubles me about "Eternal Sunshine," I have to allow that much of what's right about it must also stem directly from him: The movie is redolent with wistfulness and melancholy, and those aren't things you can layer on after the fact.

The disappointment I felt at the end of "Eternal Sunshine" was almost crushing, simply because there were sections of it that were as daring in their emotional directness as anything I've seen in years. Did Kaufman, or Kaufman and Gondry, construct the movie as they did simply so audiences wouldn't leave the theater feeling too devastated to engage in conversation, let alone a cocktail or a cappuccino? Maybe. Yet there are moments in "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind" that bring us as close as anyone should ever come to staring at the sun. The movie's warmth is irresistible; the risk of getting burned should have been left to us.

Shares