Susan Sontag infamously remarked that the white race was a cancer on humanity. To Lars von Trier, humanity is the cancer. Von Trier's "Dogville" caused a great stir at last year's Cannes Film Festival with charges that the Depression-era fable, set in a rural town in the Colorado Rockies, was anti-American. It is. But anti-Americanism is a small matter when a movie is anti-human.

"Dogville" is as total a misanthropic vision as anything control freak Stanley Kubrick ever turned out. Von Trier, for all his studied technical incompetence, is just as deliberate a filmmaker as Kubrick, but his misanthropy feels both more virulent and more conscious than Kubrick's chilly demonstrations of technical proficiency.

At three hours, and as the first film in a projected trilogy, "Dogville" strains for the epic. This is von Trier's Big Statement (or at least grandiose throat clearing). But in every respect other than sheer length -- in scope, imagination, execution, depth and spirit -- "Dogville" is a piddling movie.

That hasn't stopped it from being widely acclaimed as a masterpiece. Are the critics who are rhapsodizing over "Dogville" actually swallowing its puny, rancid view of humanity or are they afraid that slamming it means they'd be showing themselves not tough enough to take its hard truths? Reading the raves for "Dogville," I've thought of the girl in Michael Ritchie's "Semi-Tough" who announces at an encounter group, "I peed in my pants and it felt good." Except that to get any pleasure out of "Dogville" you'd have to say, "I was peed on and it felt good."

Bullies can be just as persuasive in the arts as they are on the playground and von Trier is nothing if not a consummate bully. An American critic who slams "Dogville" opens him- or herself up to the usual charges of Americans being unwilling to face the ugly truths about their country (no matter how facile or smug or uninformed those "truths" are). But any critic who rejects the film is open to being told they can't accept dark, pessimistic art, that they'd prefer nice movies. That's a very macho vision of the arts, in which the "hissing naysayers" (as one critic called those of us who reject the film -- and let me own up: When I saw it at the New York Film Festival last fall, I hissed) should just go back to our nice humanist movies and leave the heavy lifting to the tough-minded.

But put "Dogville" next to the juice flowing through any great, vital misanthropic art, from Swift to Thackeray to Celine (to W.C. Fields, for that matter), and the thesis dryness of von Trier's work becomes clear. Artists can be just as withering as they like about any milieu, any period, as long as they allow the characters to be fully formed and not just stick figures set up to make their points. "Dogville" is getting talked of as being a raw and demanding experience, but the educated, liberal moviegoers who will constitute its audience won't hear anything they aren't already primed to hear. Von Trier is preaching to the converted here as much as Mel Gibson is in "The Passion of the Christ," and those of us who aren't ready to hear the message are, to von Trier's acolytes, just as much heretics.

As was "Breaking the Waves" and "Dancer in the Dark," "Dogville" is about the degradation and torture of a beautiful young woman. (The critic Greg Tate nailed it in the Village Voice when he referred to the director as "Lars 'The Bitch Killer' von Trier.") In this case, as in "Breaking the Waves," it's specifically sexual torture.

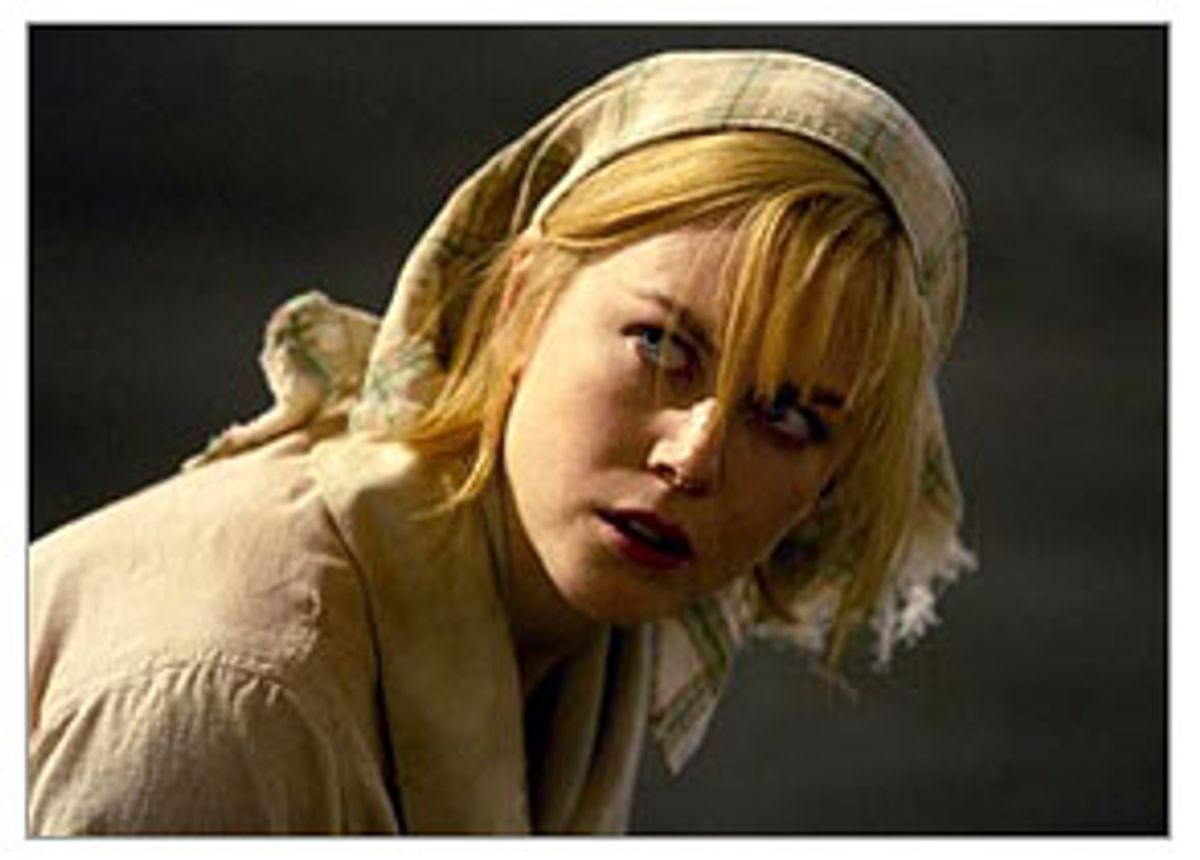

Nicole Kidman plays Grace (cue the distant drums of approaching irony), a fugitive (from what we don't know) who turns up on the outskirts of Dogville. The town's resident young intellectual, Tom Edison (I swear I'm not making that up; he's played by Paul Bettany), has been exhorting the mostly bored townfolk to improve themselves, and in Grace he sees his chance to help both them and her. Tom convinces the residents of Dogville to allow Grace to help them with their chores, in exchange for which she'll be given room and board. Grace's hard work and sweet smile soon make her a welcome addition -- until strangers come to town bearing wanted posters with Grace's face and offering a substantial reward.

From there "Dogville" becomes the longest exercise yet in the Lars von Trier Theatre of Cruelty. When Grace tries to get away, a cement wheel that she has to drag everywhere is attached to a manacle around her neck. Grace is raped repeatedly, and used by the men as the town whore. And the women find ways to inflict their own humiliations. (Three hours allows for a lot of humiliation.)

But where the whipping posts played by Emily Watson in "Breaking the Waves" and Bjork in "Dancer in the Dark" are sacrificial victims, Grace is von Trier's avenging angel. She gets her revenge in the end, and it's so much worse than what's been inflicted on her that whatever sympathy we might have had for her (or, to put it more specifically, for Nicole Kidman's heroic attempt to give a performance in this swill) is rubbed in our face.

It's clear that's what von Trier intends. He wants, I think, to fool us into identifying with Grace, though by the end we're meant to be in the same position as Tom. Our sympathy for Grace mirrors his good intentions. That she turns so villainous is meant to make both good intentions and sympathy seem the province of fools.

If von Trier were simply making the point that the victimized often become victimizers, trite as that is, it would be hard to argue with him. But Grace is fulfilled by becoming the bloodthirsty vengeance demon she turns into in the film's climax -- just as Emily Watson's and Bjork's characters were fulfilled by being murdered and executed. Essentially, von Trier's worldview is no different than that of the most macho pulp writer: In his world, it's kill or be killed. And it doesn't much matter who does the killing and who does the dying because, for von Trier, we are all rotten at the core.

He may find all human beings equally despicable, but that doesn't mean that they suffer equally in his films. Women are von Trier's select victims. That alone doesn't make him a misogynist. What does make him a misogynist is the sadistic relish he takes in the drawn-out destruction of his female characters, which we see as if watching flies having their wings pulled off under a microscope.

Because of the style in which "Dogville" has been shot -- entirely on an indoor soundstage, with chalk outlines on the floor standing in for buildings, and sound effects for things like closing doors -- the actors mime many of their actions. But damned if Nicole Kidman doesn't actually have that concrete weight manacled to her neck. In a von Trier movie, how could it be otherwise?

The director's supporters have tried to explain away the treatment of women in his movies by invoking spiritual or political themes -- "Breaking the Waves" was about the quest for salvation and the sacrifices we make for love; "Dancer in the Dark" was a protest against capital punishment and so forth. But Bjork's execution in "Dancer in the Dark" went on for an obscene amount of time. And long after we've gotten the point in "Dogville," Kidman is still being raped and abused. No matter what point he is allegedly making, we are still watching the protracted depiction of women being raped and killed and otherwise abused.

Speaking about the control he requires of actors in a recent interview, von Trier said, "This is why I work so often with females. To give up control you have to trust somebody, and it's easier for me to convince females to do this, for some reason." He doesn't convince them for long, however. Has anyone noticed that actresses tend to get the hell away from von Trier after working with him? Following "Dancer in the Dark" Bjork announced that it was such a miserable experience she would never act again. And Nicole Kidman (citing scheduling conflicts) has pulled out of the next two films in the projected trilogy.

Given that style, "Dogville" is essentially a filmed stage show -- a bad piece of '30s avant-garde theater, to be specific. But the "open" stage plan serves a metaphoric meaning. That the worst takes place in plain view of everyone else (imaginary walls or no) is meant to implicate all the characters equally in every horrible act. Everyone is guilty (which, of course, means no one is).

Von Trier has borrowed both from Friedrich Durrenmatt's play "The Visit" and from Thornton Wilder's "Our Town." John Hurt narrates the film in a voice as dry as a corn husk, though with just enough vinegar to make it clear that the homiletics his lines consist of are intended as a parody of the narrator in Wilder's play. It's easy to see that von Trier would have contempt for as sweet and loving and achingly poignant a vision of American small-town life as "Our Town." He wants to expose Wilder's vision as a lie.

But von Trier, in whom the dunderheaded and the heavy-handed meet, also misses what's great about his darker source. In "The Visit," a fabulously wealthy woman returns to the impoverished town she left in disgrace years before and offers the townspeople a million dollars to kill the man who wronged her. Durrenmatt's writing is sharp and uncompromised and also very funny. The fabular elements have a pointed playfulness to them. Durrenmatt presents the most appalling things with a fleet absurdity. "The Visit" moves swiftly and surprisingly to its climax. Von Trier grinds away at each instance of cruelty and hypocrisy like someone screwing a cigarette butt into an ashtray long after it's gone dead.

And he means to be just that numbingly insistent. Von Trier is fully in command of his effects and his meanings. The imaginary sets of "Dogville" may be the opposite of what the Dogme 95 manifesto, which von Trier co-signed, mandated (shooting with a hand-held camera on location in direct sound, no special effects or lighting, and so forth). But the effect is of the same malnourished purity as the Dogme films. This is moviemaking as penance for the filmmaker and punishment for the audience.

Shot by Anthony Dod Mantle in watery, grainy color, the endless close-ups waver drunkenly on the screen. The movie is just as washed-out and ugly looking as "Breaking the Waves" and "Dancer in the Dark" were. (To talk about the aesthetic qualities of a von Trier movie is a joke.) The enforced drabness is summed up by what may be the most shocking sight in all of "Dogville": that of Lauren Bacall hoeing potatoes -- worse, miming hoeing potatoes. I keep thinking of moviegoers who saw "To Have and Have Not" when it opened in 1945 and were bowled over by that stunning, sexy, sarcastic girl: Did they ever imagine that one day they'd have to see her in a peasant role?

No matter how much von Trier disdains the slickness epitomized by Hollywood filmmaking, he's the unconscious heir of the hokey movie tradition of casting stars in roles unsuited to them. In one of their comedy routines Nichols and May once joked about Sal Mineo being cast as Ernest Hemingway. Is seeing Catherine Deneuve playing a factory worker in "Dancer in the Dark" any less ridiculous? Von Trier clearly thinks he's taking stars down a peg by casting them in these unglamorous roles. But he's also depending on their glamour to get people into the theater. And the only thing that sustains you through "Dogville" are the moments of movie-star glamour that Nicole Kidman projects.

Von Trier has established an amazing cast for "Dogville." In addition to Kidman and Bettany and Bacall, there's Ben Gazzara, Philip Baker Hall, Patricia Clarkson, Chloë Sevigny, Harriet Andersson, Jeremy Davies, Zeljko Ivanek, Blair Brown and James Caan. And not one of them is any good. If one or two of these actors were bad, you might conclude they were having an off day. When a group this talented, who work in so many different styles, is bad in toto, it's pretty clear that the director has no talent for directing actors.

And no interest either. It was a shock to see Harriet Andersson's name in the end credits. This is one of the great actresses who made her mark in Ingmar Bergman films like "Monika" and "Smiles of a Summer Night" -- and in "Dogville" she's simply tossed away in the undistinguished part of an old lady who runs the town store. The part could have been played by anyone, but von Trier's disdain is, I think, indicative of how little feel he has for films and for people. He's willing to turn anyone, no matter how great, into one of his pawns.

Von Trier is a conscious provocateur. He wants to pick at scabs, and I'm betting that he hopes people detest his movies as much as love them. For a director like von Trier, the former response is much more valuable, proof that he has touched a nerve. But he's the most humorless provocateur imaginable. With "Dogville," it's obvious that he wants to needle people into a response, and also obvious that if you are needled, you've taken his bait.

More than anything, that makes von Trier seem a director perfectly suited to this moment in the movies when ironic detachment is paramount. At nearly every stage of von Trier's career, from Dogme to "Dogville," there have been supporters ready to talk about him as a joker whose provocations are just provocations. Again and again in the reviews of "Dogville," you can read that the movie is not meant to be taken literally, that it's hard to take seriously, that what happens shouldn't really affect us because the movie operates as a fable or a fairy tale. Essentially what that view says is that the people in "Dogville" are as representational as the buildings we are left to imagine, that they are just stand-ins, and that what happens to them doesn't really matter as long as we get the point.

That way, I think, lies the end of any useful concept of art, the acceptance of any brutality as long as it's in the service of an idea, the encouragement of the belief that, since nothing that happens in a movie is real, it need not be taken seriously, that the people on the screen are actors and we shouldn't get worked up over how they or their characters are treated.

But the people we see in the closing credits of "Dogville" aren't actors. They are the subjects of photographs from the likes of Dorothea Lange and the Danish photographer Jacob Holdt's "American Pictures," a montage of the poorest and most damaged and wretched of Americans from the Depression to the present. Over this montage we hear David Bowie's "Young Americans." Are we meant to take these people as mere representations as well? Are we meant to have any human or aesthetic reaction to the misery these pictures show or just take them as proof of the three hours of playacting that has preceded them?

If there's any irony to "Dogville" it's one that von Trier hasn't intended. The movie is being acclaimed as a great indictment of the incipient fascism in American life, or a powerful statement about human venality. And yet it's been made by a director who sees his job as that of a puppet master ("To give up control you have to trust somebody, and it's easier for me to convince females to do this, for some reason"), who is willing to sacrifice the talent on-screen and the characters they portray to the greater glory of his "vision." If von Trier's supporters are really concerned with the themes of power and freedom and enslavement he pretends to address, should they really be kissing the backside of the fascist behind the camera?

Shares