Aesthetically exciting and sick as hell, "Sin City" is so disreputable that it practically turns itself inside-out into a spectacle of virginal innocence: Blunt, devoid of metaphor and unapologetically depraved, it radiates a perverse kind of purity. In the early minutes of the picture, an aging cop with a bad ticker prepares to shoot the nuts off a child molester -- but first, he shouts a warning to the terrified 11-year-old girl he's just rescued from the sicko's clutches: "Cover your eyes, Nancy! I don't want you to see this."

His warning is an admission that there are some things decent, God-fearing folk just aren't fit to see, and an assurance that "Sin City" is going to catalog them dutifully and in exacting detail. As tawdry spectacles go, "Sin City" is scrupulously honest. Like an unfiltered Camel, it delivers tar and nicotine straight to the system, with no fussy preamble.

The directors of "Sin City" are Robert Rodriguez (who made the 1993 low-budget groundbreaker "El Mariachi" and its two sequels, as well as the "Spy Kids" pictures, the first two of which are wonderful) and Frank Miller, the creator of the pulp comic-book series on which the movie is based. "Sin City" is a rare instance in which a comic book's creator has been invited to participate in a film adaptation in any meaningful way. That's significant, now that the world of comic books has become such a salmon farm for moviemaking.

There have been marvelous comic-book movies in recent years (Guillermo del Toro's "Hellboy") as well as lavish but limp-spirited ones (the two "Spider-Man" pictures). But "Sin City" looks nothing like either of those movies. Theoretically, comic books are natural source material for the movies, but even the best ones often feel simply like movies with comic-book elements grafted on. "Sin City," on the other hand, is brazenly organic, like a novel made of moving pictures. Highly stylized and meticulously styled (it relies largely on digital compositions and was shot with a digital high-definition camera), it lacks the loose, crazy feel that can make movies feel so alive. On the other hand, so many conventional pictures these days forbid loose craziness to begin with. "Sin City" may be a digitally controlled universe, but it's one that glints with hard, glittery life.

That's essential, because pulp needs life; even the very word "pulp" suggests something moist, alive and blood-gorged (even though, historically speaking, the term refers to the cheap paper on which pulp novels were printed). Rodriguez and Miller have adapted three Miller tales and pieced them together into a movie with a pulse. "Sin City," as Miller has mapped it out in his books, is an urban landscape of busted promises and dreams shot full of bloody, gaping holes, a place where corruption thrives and nobility and virtue are choked off whenever they attempt to take a breath.

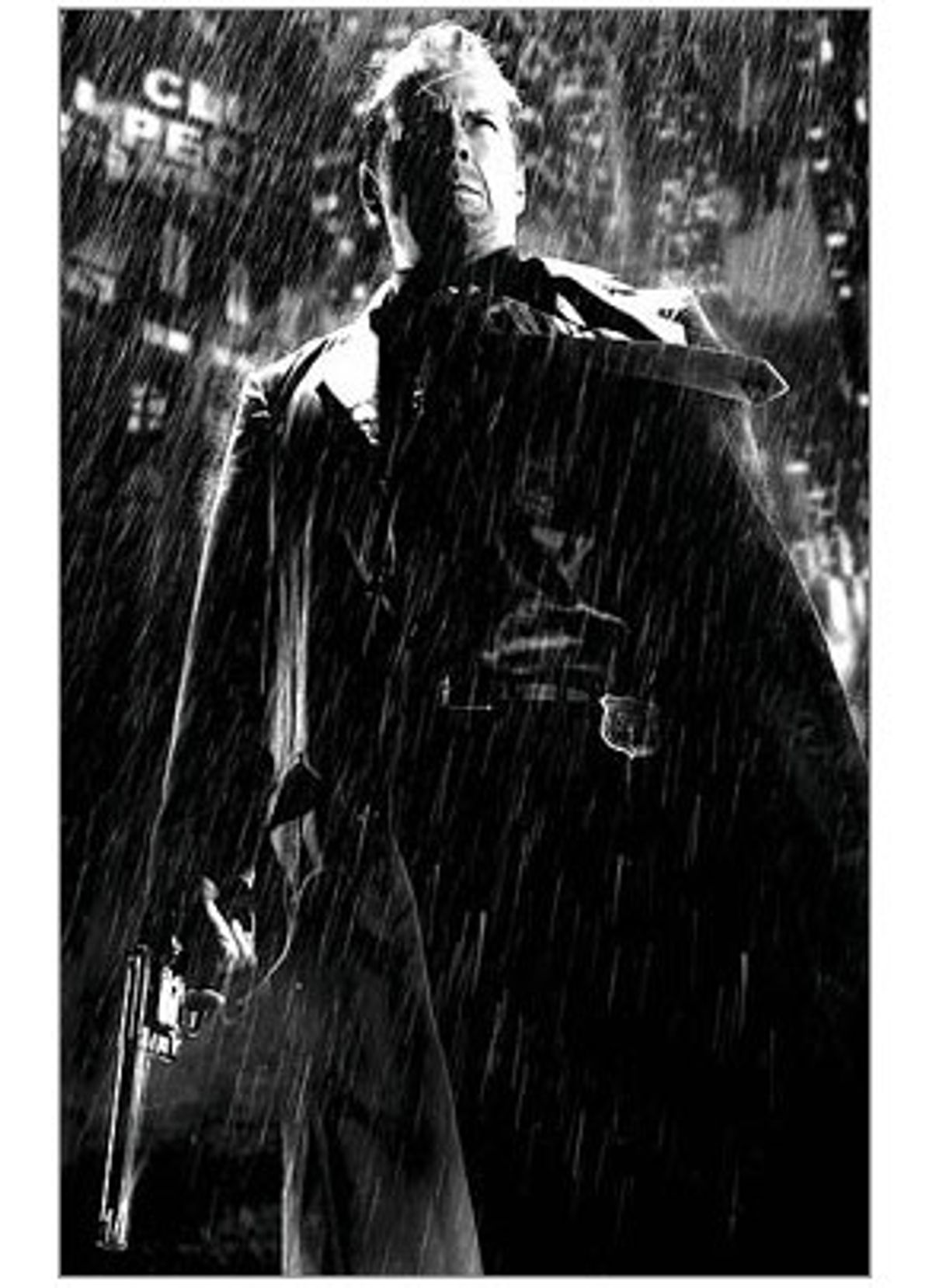

This movie Sin City is patrolled restlessly by people like Bruce Willis' Hartigan, the last honest cop in town, a guy who risks his life to save that of a little girl, only to find that no good deed goes unpunished. Mickey Rourke (in heavy prosthetics) is Marv, a hulking square-jawed, sad-eyed loner who sets out to avenge the death of a hooker named Goldie (Jaime King), one of the few people to extend genuine kindness to him. And Clive Owen is Dwight, a detective who moves through the city like a perennial 5 o'clock shadow. So seemingly well-adjusted he has the potential to go truly nuts, Dwight sets out to protect his new girlfriend, cocktail waitress Shellie (Brittany Murphy), from her wacko ex-boyfriend (Benicio Del Toro) and ends up running into his real true love, a black-leather-clad Sadean goddess named Gail (Rosario Dawson), whose pull on him is sexually and spiritually magnetic. (In their grandest scene together, he beams at her after the two have fended off a whole neighborhood of evildoers in a rat-a-tat blood bath and, in voice-over, tenderly proclaims her his "Valkyrie.")

The interwoven plots of "Sin City" draw in a motley clan of peripheral characters, including a lesbian parole officer with a tough heart, sterling principles and heartbreakingly luscious curves (Carla Gugino); a deadly, whisper-quick warrior girl (Devon Aoki); a sweet-natured stripper beloved by every decent person who knows her (Jessica Alba); and, perhaps most unsettling, a spritely werewolf boy in a neon-nerdy Charlie Brown jersey (Elijah Wood) who whisks women away to his remote farm, where he eats the body parts he likes and throws the rest to his dog.

Did I mention that "Sin City" is sick as hell? The atrocities, some of which will make you feel at least vaguely ill even as you laugh at them, include ears and various other body parts being blown off with gusto, sternums being pierced with thick, sharp objects, lead pipes cracking remorselessly against human skulls (the sound design of "Sin City" is sometimes harder to take than the images), and numerous guys being axed or otherwise compromised in the crotch (this particular theme seems to be a favorite, as "Sin City" views dumb machismo as the world's least valuable commodity). When a wrongly accused criminal finally hits death row ("They shaved my head and fit me with a rubber diaper"), he taunts his executioners when the first jolt of electricity isn't enough to kill him: "Is that the best you can do, you pansies?" he growls, as thick waves of blood gurgle from his mouth.

If you're waiting for a "but" here -- something about redemption or the ultimate imparting of solid moral values -- you're not going to get one. "Sin City" isn't an emotionally complicated picture or a particularly deep one, and its freshness lies in the way it refuses to pretend that it is. That said, "Sin City" does have a steel-beamed moral infrastructure -- Miller's view (and Rodriguez's too) of right and wrong, goodness and evil, frames the movie as solidly as, well, the bars around a comic-book panel. And the movie's sexual politics are straightforward but not necessarily retrograde: The safest and sanest part of town (relatively speaking, at least) is the section that's populated and run by its prostitutes, who know what's what and conduct themselves accordingly. They understand the nature of men better than men themselves do -- not a new idea by any means, but one that refuses to buy into the idea of women as simpering victims who need to be protected.

Part of what makes "Sin City" work is that while the performances may be somewhat broad (they need to be, to suit the material), they stop at being grotesquely cartoonish. Owen is always a dazzling, uncompromising presence, and he puts his considerably roguish charms to work here, too. Accosting a bad 'un in a bathroom -- where else does one inflict near-drowning-by-swirlie? -- he introduces himself with the stunningly original line, "I'm Shellie's new boyfriend, and I'm out of my mind." Willis, so big a movie star that he's rarely given credit for being a terrific actor, brings a strong measure of tough-guy melancholy to his role here. And although Rourke is barely recognizable beneath his makeup and prosthetics -- he resembles a beefed-up, mutant Kirk Douglas -- he allows the roughed-up soul of his character to shine through.

Despite the fact that so much of "Sin City" was constructed digitally (the actors performed against green screens; backdrops and details were filled in digitally after the fact), there's something refreshingly elemental about it. Unlike, say, the visually intriguing but empty "Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow," "Sin City" is a technological achievement that nonetheless recognizes that there are still plenty of human beings who value movies over mere achievements. Miller's "Sin City" books are Old Testament-style tales of vengeance set in a gritty noir-fantasy world. His black-and-white drawings are so stark they resemble stencils -- they're like urban versions of medieval woodcuts, fables of right and wrong reduced to their barest elements.

The movie "Sin City" is also black-and-white -- which means, of course, that it's really black, white and infinite shades of gray -- accented with judiciously used splotches of color: The skin of a creepy villain glows jaundice yellow; a curvaceous blonde wears a crimson dress that matches the juicy color of her lips. Those colors float on the velvety surface of the picture, a tribute to the notion that all black-and-white movies are really in color, anyway -- colors that we fill in for ourselves. And in some scenes, blood is white instead of dark -- maybe a challenge to the way we treat bleeding bodies as business-as-usual in action movies.

In addition to directing, Rodriguez also shot and edited the movie (he also wrote some of the music). And while what I'm about to say most likely amounts to heresy in cinematography circles, he manages to capture at least the spirit, if not all the stark, eerie beauty, of the great film noir cinematographers -- people like Russell Metty, who shot Orson Welles' "Touch of Evil," as well as the numerous journeyman cinematographers whose names are less well-known but whose work amounts to a kind of textbook of the craft.

As a champion and protector of traditional filmmaking technique -- that is to say, of movies shot on film -- I'm pained to admit that "Sin City" looks as great as it does. Rodriguez goes for all the right noir touches, translated directly from Miller's drawings: Nighttime rain falls down in tinselly sheets. Figures are framed in chiaroscuro doorways. A heart-shaped bed is shot from on high, like a candy-box valentine to illicit love.

Maybe I should be railing against some perceived soullessness or lack of warmth in the visual surface of "Sin City." But the sorry truth is that while plenty of "real" cinematographers would jump at the chance to shoot a noir-style black-and-white picture, those types of movies just don't get made today. A cinematographer can hone the craft for years, and be fully devoted to it, and end up making much of his or her living off remakes of old cartoon shows and '70s TV series. How can we fault Rodriguez for using the technology he's got to such astonishing effect? Whatever his means, by caring enough to re-create and reimagine classic noir, he honors it.

I don't want "Sin City" to represent the future of filmmaking. But it says something that "Sin City" is the first mainstream American picture I've seen this year that feels even remotely brash or original. It's a hard, viciously funny little movie, one with all the subtlety of a billy club. But there's artistry here, too, shining out like the harsh wedge of a flashlight beam. Although "Sin City" isn't, per se, a Hollywood movie (everybody knows that movies are no longer made in Hollywood anyway), as a big Miramax release, it does qualify as "Hollywood." Some moviegoers, and probably quite a few critics, are likely to denounce it as needlessly sleazy, deplorably violent and downright repugnant. But "Sin City" is the movie it needs to be: A rough beast crawling forth from a town without pity, it's gotta have balls -- or else.

Shares