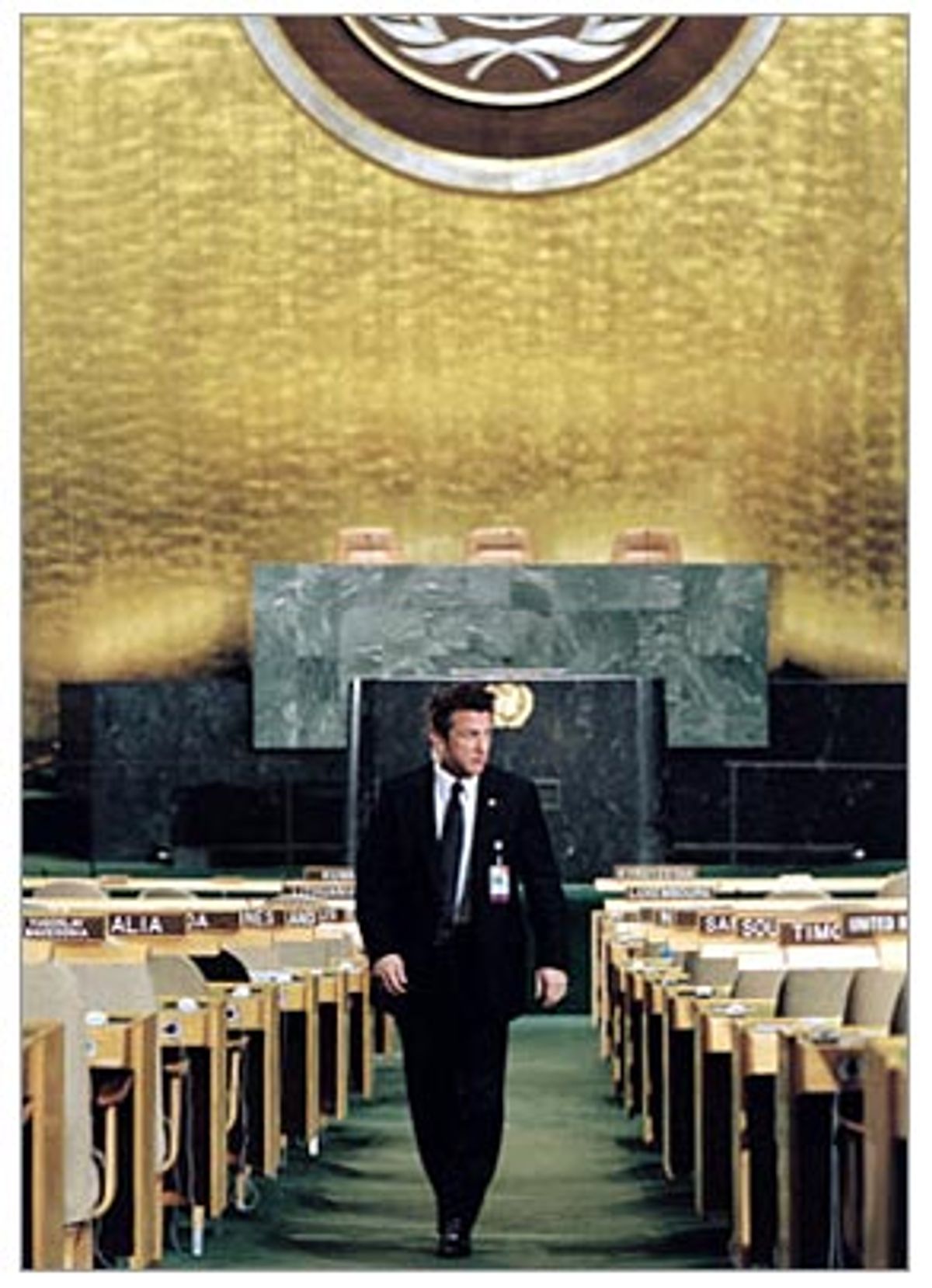

Come, let us now praise the resplendent attention to detail evident in Sydney Pollack's latest jewel-laden elephant, "The Interpreter," an exercise that will take far less time than the act of sitting through the damn thing: The picture was filmed, for real, within the hallowed halls of the United Nations (a privilege that was refused even to Alfred Hitchcock, when he tried to shoot portions of "North by Northwest" there); it's set in its own imaginary Southern African country, Matobo, which has a wholly made-up language, Ku, to go along with it; and it features Sean Penn, as a federal agent whose wife has just been killed in a car crash, stalking pensively through his daily routine, which happens to include guarding the endangered Nicole Kidman, an African-born U.N. interpreter who may or may not be complicit in a plot to murder a Matobian dignitary.

Not since "Shark Tale" has cinema given us such a blend of realistic detail and whimsy. And while it pains me to beat up on Pollack, who, in addition to being a consistently wonderful actor, is at least attempting to make movies the old-fashioned way, it pains me more to actually sit through his movies.

"The Interpreter" seems driven by a powerful, droning mantra more than by the momentum of the plot (the script is by Charles Randolph, Scott Frank and Steven Zaillian, from a story by Martin Stellman and Brian Ward). Each scene is so carefully crafted that it sits, polished and lifeless, on the screen -- there's no flow, no movement, between those scenes, and the story is hard to follow simply because it's so hard to care about it. "The Interpreter" is so intent on reminding us that it's a quality piece of work that it forgets to give us the very thing we thought we came in for: a story.

Kidman plays Silvia Broome, who, with her trim, no-nonsense haircut, resembles a very businesslike pixie. Not many people can speak Ku, but boy, Silvia can. Matobo is her homeland, and she's deeply familiar with the country's history of strife: its post-colonial struggles, its history of unrest between tribes, its corrupt leadership. Although she now works as a U.N. interpreter, she may have a shady history as a revolutionary -- why else would she appear in a group photo with other assorted disgruntled types? (As group portraits go, this one is just a shade more realistic-looking than Peter Blake's cover for "Sgt. Pepper's." I laughed when I saw it, thinking, mistakenly, that its obvious Photoshop quality was an intentional plot detail.)

One day, Silvia returns to the U.N. after work hours and overhears a fragment of a threat, spoken in Ku: Apparently, someone is planning to kill Matobian president Edmund Zuwanie (Earl Cameron), a once-benevolent dictator who has betrayed his people and been charged with genocide. Federal agent Tobin Keller (Penn) is assigned to protect Silvia, but he also wonders if she may be involved in the murder plot. Keller has just lost his wife; Silvia seems to spend her evenings taking flute lessons: The two begin a delicate cat-and-mouse game in which their parallel loneliness is explored in sensitive green-gray tones (the cinematographer is Darius Khondji, who gives the picture an efficiently moody look).

Penn and Kidman, serious stars for a serious movie, are allegedly the big draw here, but it's hard to suss out any kind of connection between them. Kidman is adequately believable, if believability is what you're after. But the buttoned-down gravity of the movie doesn't bring her best qualities (among them her kittenish playfulness) to the fore. And although Penn is somewhat stony and vague here, his performance is wholly inoffensive. Maybe that's exactly the problem: There's always something going on in that noggin of his, and he never lets us forget it. We begin to fixate more on the significance of the occasional frown, or the faraway, glazed look that sometimes comes over him, than on the character he's supposed to be playing. This isn't a bad, overworked performance (the kind Penn, a sometimes-great actor, is all too capable of giving), but it's a dull, inert one.

Then again, "The Interpreter" does take place in that bastion of excitement we call the United Nations. The press notes for the movie are more entertaining than anything we actually see in it: "In the power-brokering halls of today's United Nations -- where wars, disasters and global crises are addressed and sometimes averted on a regular basis -- every single word counts." Well, OK, some of those words probably count, as long as we're not talking about WMD and stuff.

There are occasional signs of life in "The Interpreter": Catherine Keener shows up here and there as Penn's partner, and her brisk, down-to-earth flirtiness gives the movie its only note of sex appeal. (Though her character is named Dot. Who the hell casts Catherine Keener as a "Dot"?) And Pollack himself, appearing as Penn's crotchety boss, lights a match to his own picture in his few brief scenes. He instructs Penn to protect the targeted president during his U.N. visit by doing "whatever you need to do to keep this maniac's heart beatin' until he gets out." It's the kind of line that looks dead on the page, but Pollack puts so much spring in it that you have to laugh.

Whenever Pollack appears, in even the dullest movie, I marvel at how he can bring a scene to life without even trying. So how is it that as a director, his specialty has become making pictures with a dull, serious sheen, pictures that pretend to give us what we want in a movie entertainment and yet send us home empty-handed? "The Interpreter" may seem expertly crafted, but the effect is just an incredible simulation. When it moves its lips, nothing comes out.

Shares