"Ladies in Lavender," the directorial debut of actor Charles Dance, is the kind of small, fine-boned English picture that's usually sold with one of those deadly art-house-cinema trailers. You know the kind: The actors' most emotive moments are plucked out of context and put before us against a backdrop of swollen string music. Sometimes there's even a handy voice-over to alert us to significant plot points: "Two lives will be changed forever by a stranger" -- that sort of thing.

Trailers like these are designed to attract the widest and dullest possible audience, but so often they do a disservice to the very movies they're trying to sell. Personally, I'd run a mile from "Ladies in Lavender" if it were the kind of movie its trailer wants us to think it is. But the movie itself, sensitively but sturdily made, with an ear attuned to the most delicate notes of the story, is the sort of small, independent-minded picture that so much of American indie cinema strives, and often fails, to give us. It's a conventional picture, but it feels so deeply alive that it's practically a novelty.

Ursula (Judi Dench) and Janet (Maggie Smith) are two elderly unmarried sisters living together, in the cliff-top home they grew up in, in Cornwall. The story opens in the late '30s; as the picture unfolds we learn that Janet has been married before (her husband died in the Great War), but Ursula doesn't seem to have had many suitors, if any, in her youth. One morning, after a storm, the two women step out into the garden in their nighties to find out how much damage the wind and rain have done to their plants. They look down to the shore and see that a man has washed up there overnight; he lies face-down on the beach. The two women, clutching their dressing gowns around them, rush down to see if he's still alive. ("I suppose the sensible thing would be to turn him over," Janet says.) Finding that he's still breathing, they get help and tuck him into one of their spare beds, waiting anxiously for him to come to.

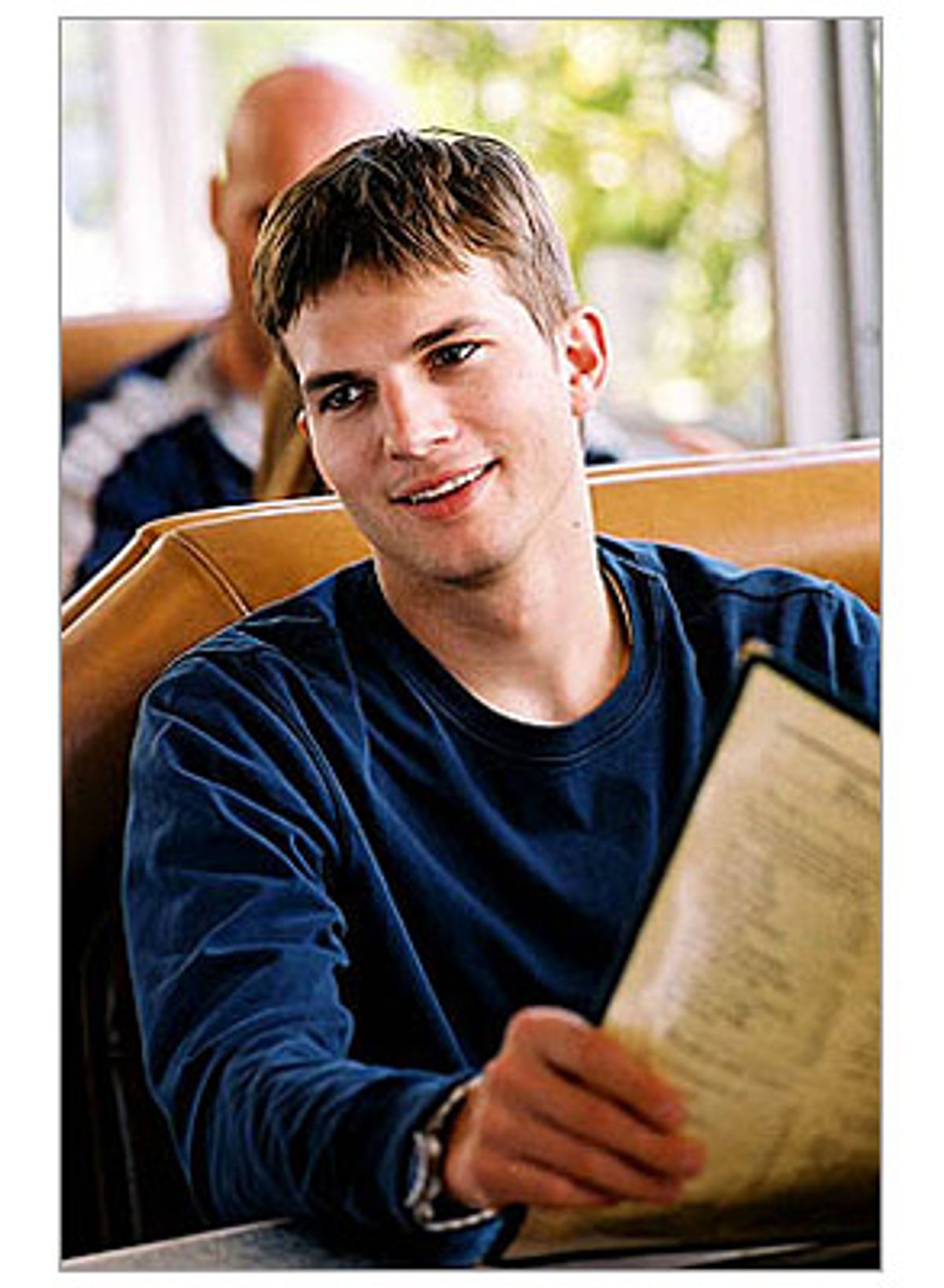

The young man's name is Andrea (he's played by Daniel Brühl, the expressive, likable young star of 2003's "Good Bye Lenin!"), and he speaks only Polish and German. The story that follows is relatively simple; as we learn more about who Andrea is, and what role he comes to play in the sisters' lives, the picture takes on deeper and more delicate textures.

Dance adapted the script from a short story by a nearly forgotten author named William J. Locke. (Dance was doing a film in Budapest and started flipping through one of the many books that were being used as set dressing; it was a collection of short stories by Locke, which Dance took it upon himself to "liberate.") The picture is simply made with a minimum of gimmickry. In a few places, Dance can't leave well enough alone: He uses some slow-motion and flashback effects that feel superfluous and clichéd. But mostly, he trusts the story, a seemingly simple skill that some filmmakers never get around to learning. And he recognizes that the strong landscape of Cornwall has to be a character in the movie: Its fierce jagged shores look like no other place on earth, and even the light has a rough, vital quality. (The fine cinematography here is by Peter Biziou.)

And beyond all that, we have the pleasure of watching Maggie Smith and Judi Dench. (The solidly entertaining supporting cast includes Miriam Margolyes, David Warner and Natascha McElhone.) Smith plays the sensible sister, the one who's grounded in reality every minute. But she's deeply moving in the way she reveals, scene by scene, the silky-strong quality of the bond she has with Ursula, and the way her annoyance with her sister is bound up with passionate protectiveness. And Dench, hands down one of the most beautiful actresses now working, is so radiant here that you can barely take your eyes off her. There's a strong current of sexual precociousness in the performance. Her Ursula is elfin and flirty, not in a way that's inappropriate but in one that's simply ageless.

While actresses dread, understandably, arriving at that point in their careers when the only thing that's left to them are "old lady" roles, neither Smith nor Dench seem too worried about it. They both understand that the trick lies not in playing an age but in playing a character. Their best years aren't behind them but inside of them.

Shares