"Mr. and Mrs. Smith" opens with a marriage-counseling scene in which the two principals -- Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt, as Jane and John Smith -- face off against each other with us, and the camera, as their only witnesses. Their body language is stiff and reserved; their elbows and knees seem to be poised at combative angles. Each assumes an air of rational indifference, but surreptitiously, the two of them glare at each other like zoo cats with a beef. The marriage counselor pokes the usual questions through the bars of their cage -- How did they meet? What is their sex life like? -- but we can't see him; it's as if the poison fumes pouring off them have erased everything about him but his voice. Jane and John Smith have a problem: Each, unbeknownst to the other, is in the employ of an opposing organization.

In other words, they're two people attempting to be a couple.

There are relatively few romantic comedies about marriage or long-term couplehood (the most obvious examples are the Tracy-Hepburn collaborations like "Adam's Rib"), simply because the romantic-comedy formula is all about getting there (or returning there, as in "The Philadelphia Story"). After that, Mr. and Mrs. Lovenest are on their own, and good luck to them, but we really don't want to hear about it. One of my favorite movie endings is that of Preston Sturges' "The Palm Beach Story," in which three couples, including two pairs of identical twins, go to the altar together, and once the knot has been tied, the ominous legend "They lived happily ever after ... Or did they?" appears in flowing script on the screen. It's a bitter joke, but one that recognizes that so much of the work that goes into maintaining a partnership goes on after the lights come up.

"Mr. and Mrs. Smith" isn't a romantic comedy in the strict sense. Its writer, Simon Kinberg, modeled the movie on Hong Kong action pictures, and while that angle gives it a certain bloodthirsty zest, it also creates a few problems, most notably a noisy, cluttered, protracted climax in which the gunfire is just a distraction from the far more interesting romantic banter. (Regardless, it's important to note that "Mr. and Mrs. Smith" is one of an increasingly small number of big mainstream pictures made from an original script, as opposed to being a reworking of an old movie or TV show.) But "Mr. and Mrs. Smith" understands the nuts and bolts of marriage (and I use the term to include all types of long-term relationships), and recognizes that while we all like to believe that good unions float comfortably on a featherbed of mutual respect and kind words, the reality is that as much as you may love your spouse, sometimes you just want to throttle him. But let an outsider try to drive the two of you apart, and you merge into a united front: It's probably better if you don't have to use automatic weapons, but in "Mr. and Mrs. Smith," those are just a very loud metaphor for loyalty.

John and Jane Smith are both paid assassins, although it takes almost half the movie -- and several years of marriage -- for each to figure out the other's secret. We see each of them leaving their glamorous suburban home on assignment: She, in a Kim Novak updo and black trench coat, heads out to first seduce and then snap the neck of a very naughty weapons dealer; he, in scruffy duds, with artfully arranged rooster-feather hair, is off to a seamy bar where he'll put bullets through a bunch of bad'uns in a dark, dirty backroom. John and Jane have already begun to realize that they lead separate lives, but they don't yet know how similar those separate lives are: They have more in common than they even know.

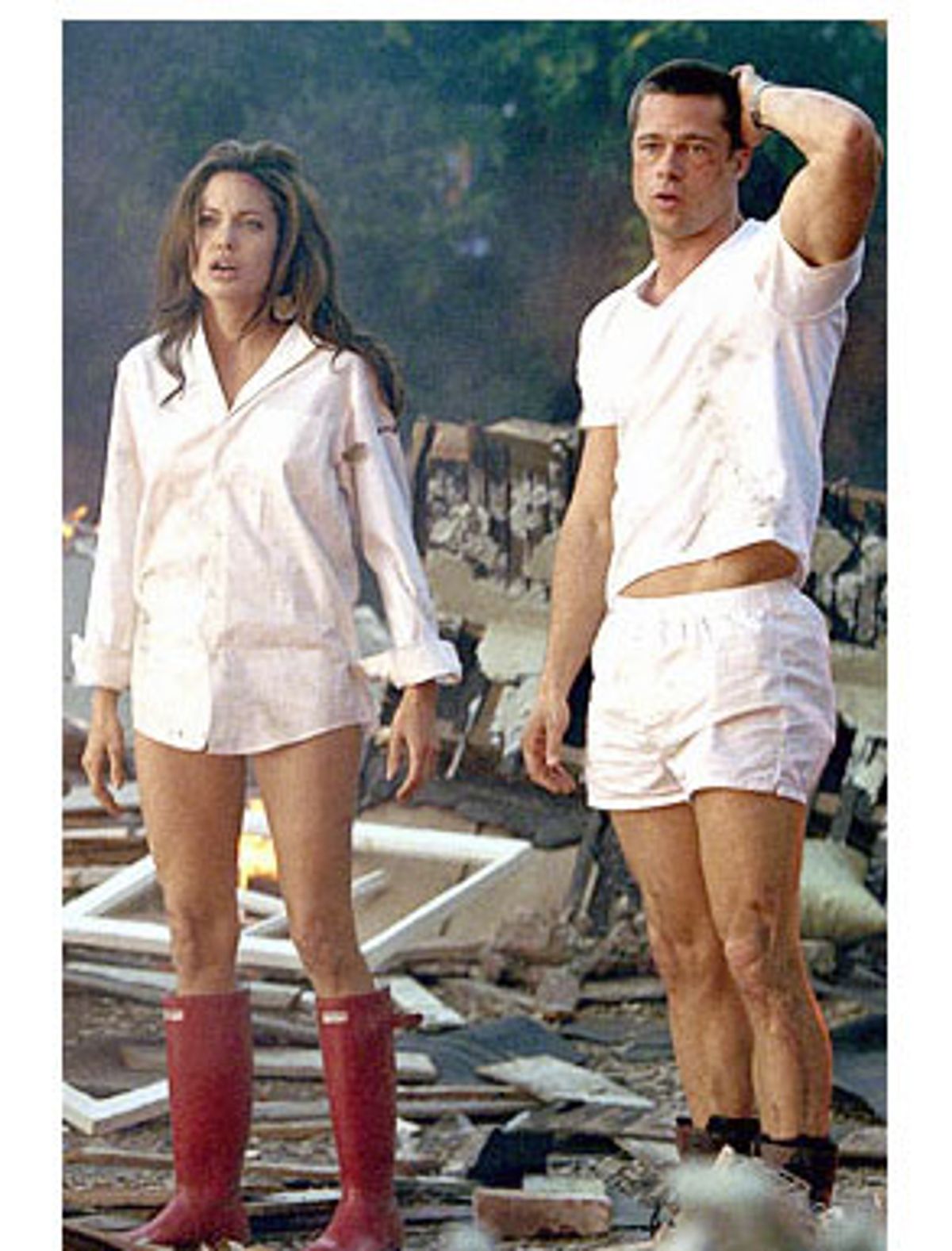

Eventually, of course, Jane's organization sends her on assignment to kill her husband. She thinks she can do it: She rationalizes it by trying to convince herself she never loved him anyway, that it was all a mistake from the beginning. When John figures out what's happening, he confronts her with wiley boyishness. They tango in a fancy restaurant, feeling each other up for concealed weapons. (We don't know exactly where her hand is, but we can guess, when he murmurs to her, "That's all John, sweetheart.") Later, with Charles Wright's "Express Yourself" as a soundtrack, they go at it with gusto -- their weapons include guns, knives, fists and feet -- turning their formerly stately home into a ravaged love nest. Director Doug Liman ("The Bourne Identity") doesn't try to downplay the brutality of this sequence: It's so vicious that I found myself laughing in awe at how far it goes -- it's funny, but it's slightly awful, too. (Liman never allows the mood to turn too sour -- Jane Smith is a more vicious fighter than John is, but when John gives it back to her, Liman takes great care with the camerawork, making the distinction between catharsis and sadism. On his watch, no one's going to get his jollies by seeing a woman get beaten up on-screen. In fact, poor John gets it much worse.)

Their reconciliation scene is as funny as their near-death battle is mock-horrifying: It's as if they've suddenly asked themselves, "What are we fighting for? We adore each other!" The sun pours through the windows of their ravaged kitchen as they go about making breakfast (she's wearing his bloodied shirt, as if to take back some of the hurt she afflicted), toasting each other with jagged-edged juice glasses. Later, they begin confessing their numerous lies and deceits: "I was never in the Peace Corps." "My real father is dead -- that guy who gave me away at our wedding was a professional actor." For the rest of the movie, they continue to raise each other's hackles, but that's inevitable: As John's hit-man colleague, played with eye-rolling devilishness by Vince Vaughn, tells him, "You guys are Macy's and Gimbel's." They need to stop competing with each other and meet in the middle.

I'm not sure that what we see between Jolie's Jane and Pitt's John is actually chemistry: Pitt is a good-looking mop of an actor, reasonably effective and enjoyable in pictures like "Ocean's 11" but snoozily dull when he's shoehorned into roles that require him to make a stab at great acting, like "Troy." But Pitt is so relaxed here, and so willing to play love's clown, that it's hard not to like him. In one of the movie's early scenes -- a flashback to the couple's first meeting, in Bogotá, where both are on assignment -- it's the morning after a particularly wild evening, and John fetches a cool glass of something-or-other to soothe Jane's hangover. She accepts it gratefully, remarking on how good it tastes. "I hope so," he says. "I had to milk a goat to get it." Pitt surely isn't Cary Grant, or anywhere close, but gives the line the same kind of insouciant spin Grant would have.

Unfortunately, though, it's difficult for any performer to stand up to Jolie: How can we cast even a glance Pitt's way when she's anywhere near? That's not to say Jolie is a selfish performer: She's the opposite of a succubus -- she breathes life into Pitt instead of sucking it out. But you can't escape the feeling that she's the movie's magnetic center, the North Pole reinvented as a very tall lily. Jolie's astonishing physical attributes -- legs, lips, eyes -- invite excessive cataloging because we don't know what else to do with them. Accepting the whole picture at once is almost blinding. Jolie has given more fine-grained performances than she does here, but her mischievous sense of fun is the draw: She knows her power, but she's not above having fun with it. Want to know the secrets of the pyramids? Just look into her eyes, reminiscent of the symbols found on the walls of Egyptian tombs. Why does the universe exist? I'm not really sure, but I am certain I can see through the silky slip Jane Smith is wearing (who wears slips anymore? Will "Mr. and Mrs. Smith" start a run on them?), and I'm pretty certain I can see the vague outline of a garter belt underneath. What was that question about the universe again? And so forth.

Jolie knows Jane is a cartoon wife, just as John is a cartoon husband. And yet the bond between them is recognizably, and touchingly, human. They barely get along, and yet they love each other dearly. Should they call the whole thing off, or should they call the calling-off off? It's a question they have to work out for themselves, if only they can stop bickering long enough to do it. Some people will see "Mr. and Mrs. Smith" as cynical, but I think its heart is deeply romantic, admittedly in an anvil-on-the-head kind of way. It's a love story not for the faint of heart. In other words, it's a lot like marriage.

Shares