The notoriously obsessive, if brilliant, director Wong Kar Wai spent four years working on his most recent feature, "2046." The picture before that, the sultry brocade tone poem "In the Mood for Love," was initially supposed to involve four months of shooting; the schedule ultimately stretched to 15. For two of the greatest faces in the movies today -- Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung, who starred in the film -- it must have felt something like being under a grueling fairy-tale spell, the sort of thing that leaves you perpetually exhausted even when you've dreamed you've gotten sleep.

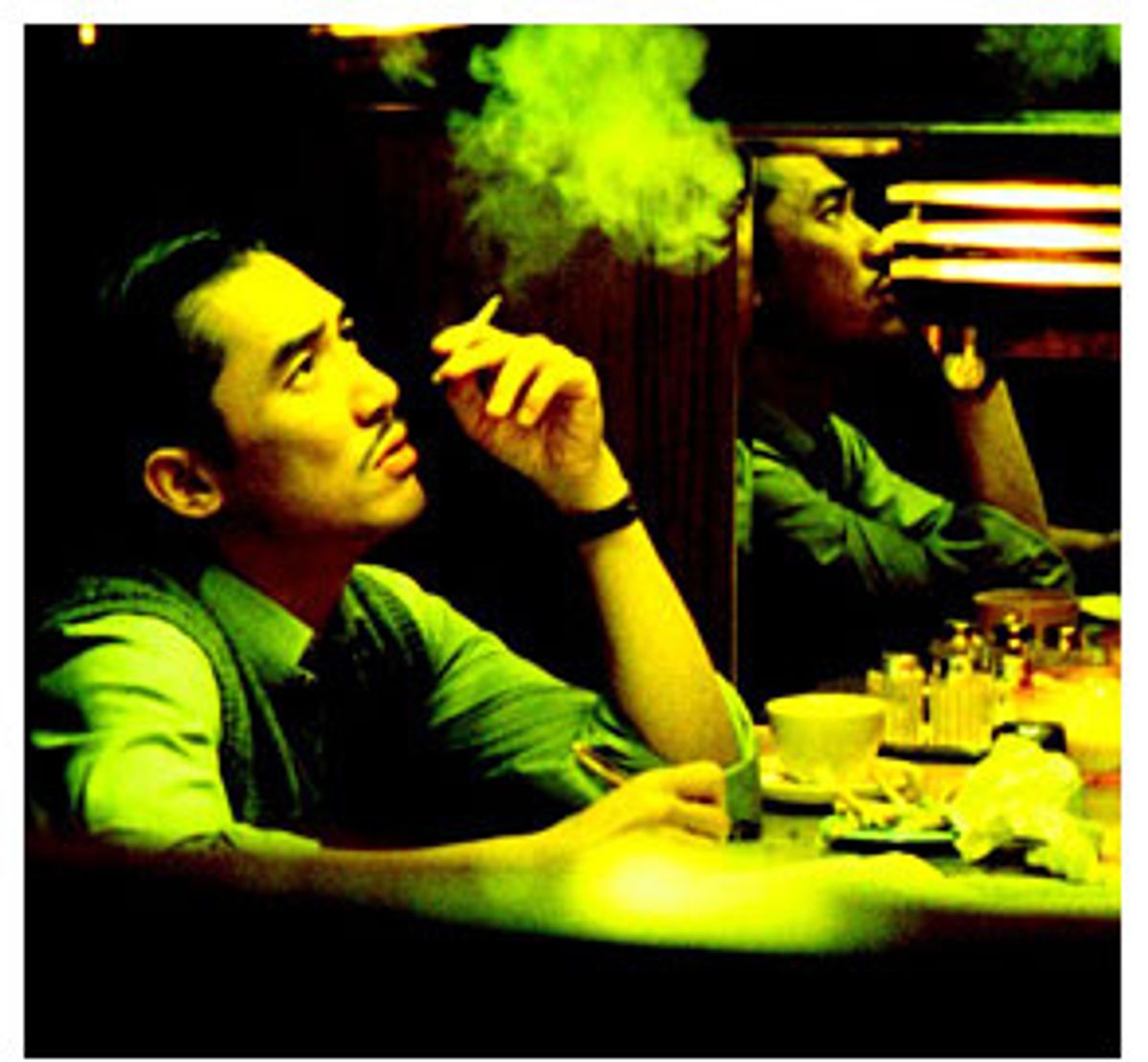

We've been told the camera never lies, but that doesn't mean it necessarily tells the truth about its motives. What if the camera, with its notoriously seductive gaze, is capable of addiction? The more it gets, the more it wants: First it has Leung for four months, then for 15. So would four years be too much to ask? The camera doesn't just love Leung; it doesn't want to let him out of its sight. He's everything it wants in a man, and more -- old Hollywood by way of modern Hong Kong -- and the camera sees a reflection of its history in his very face.

Leung, 43, has been starring in Hong Kong movies for close to 15 years. (His full name is Tony Leung Chiu Wai, and he's not to be confused with Tony Leung Ka Fai, the actor who appeared in the 1992 film of Marguerite Duras' novel "The Lover.") Leung is one of Asia's (and therefore, the world's) biggest movie stars, the sort who's perpetually trailed by gossip columnists and paparazzi. But he can walk around virtually unrecognized in New York (outside of Chinatown, that is). Even so, astute Western moviegoers have had plenty of chances to see him: The early years of his film résumé (which followed a successful TV career in Hong Kong in the '80s) include John Woo pictures like "Bullet in the Head" and "Hard-Boiled." In the past two years alone, American audiences might have seen him in the deftly multilayered cop thriller "Infernal Affairs" (he also appears in one of its two sequels) or as a third-century assassin in Zhang Yimou's "Hero." But Leung may be best known -- among Western moviegoers, at least -- for his work with Wong, which spans six pictures, beginning with "Days of Being Wild" (1991). In 2000, he won the best actor award at Cannes for "In the Mood for Love," playing Mr. Chow, a soulful, wounded married man involved in a would-be romance with Mrs. Chan (Cheung), the wife of the man with whom his own wife is having an affair. And in "2046," a semi-sequel to "In the Mood for Love," he plays a version of the same character, although it seems he's been changed and hardened by experiences that the movie only hints at.

It's an astonishing performance, one that builds on the earlier character even as it wholly reinvents it. This Mr. Chow has the same smoldering elegance as the one we met in the earlier picture. But unlike the tender, ruminative, courtly man of that picture, this Mr. Chow channels whatever damage he's suffered into a kind of emotional cruelty, largely inflicted on the fragile, sensuous call girl who has fallen for him (played by Ziyi Zhang). It's as if this Chow is a new man who, perhaps as a form of cosmic punishment, has been fitted with the painful memories of the old one, without having been granted the gentlemanly resources of kindness and compassion that might help him deal with them. Leung takes a familiar character -- one for whom, in "In the Mood for Love," we may have come to feel something like love itself, as we watch him stroll through the shimmery shadows of early-1960s Hong Kong with Cheung (who appears only briefly in "2046," like a mirage of a memory) -- and shows us both his vulnerability and his sour, ravaged core. His behavior pains us, but we can't turn away from him. His charisma goes to work on us like a kind of sweet suffering.

Those are complex strands of feeling and characterization for any actor to manage, particularly when he has no idea what the movie he's starring in is about: Wong generally doesn't give his actors scripts, instead shaping the story and characters as he goes along. And "2046" -- which is partly a story of restlessness and desire in mid-'60s Hong Kong and Singapore, and partly a deeply touching futuristic dream romance between androids and humans -- is an adamantly nonlinear, challenging picture. But Leung's performance is seamless and confident -- so much so that when I met with him briefly in New York last spring, to talk about "2046," I wasn't prepared to speak with an actor who appeared to be completely lacking in guile, to the extent that he didn't know (or, perhaps more accurately, didn't care) how to play the movie-star/interviewer game.

In other words, I expected to talk to a movie star, and a person showed up instead: It threw me totally. I don't just mean that Leung showed up in casual, comfortable clothes (which he did), or that he -- how do the people who talk to movie stars all the time usually put it? -- "picked at the salad in front of him as he considered my question" (which he didn't -- there were no salads, although he did consider my questions). We had two 15-minute conversations, split by a surprisingly brief interlude in which the publicist whisked him off to be photographed by the New York Times. (He returned to me, claiming to have told the photographer that he hadn't yet finished our interview, even though I'd been promised only 15 minutes anyway.) In person, Leung is so direct that he sometimes gives the impression of betraying intimate confidences even when he isn't; and, particularly at first, his face is so impassive that you can't read anything off it except ingrained politeness. (Most actors will give you something to read immediately, maybe partly to throw you off the trail of who they really are and what they're really thinking, but probably mostly to smooth the way for the interview ahead: They're playing a role, so are you, and it's best just to jump in and get on with things.) It seems at first that Leung simply saves everything for the camera. That's not a bad strategy as far as acting goes, but anxiety-provoking for anyone whose job it is to put him at ease -- in this case, me.

But the more I listened to Leung, the more I suspected that this soft-spoken, pensive guy recognizes the difference between being a movie idol in his own mind, and in his heart. He told me things he has told numerous other interviewers who, in their allotted 15 minutes, asked precisely the same questions that I did, which is only fair: The same questions deserve nothing more than the same answers. At one point, he explained to me why he loves acting as much as he does -- largely because "you can hide behind someone and express your feelings; you can cry in front of others without being shy." Then he looked at me squarely and said, without even a hint of self-consciousness, "I'm a very shy person with very low self-esteem" -- not as if he were confiding anything particularly personal, but as if he were stating an irrefutable fact. I've since found other interviews in which Leung has said almost the exact same thing, which I see not as an exhausted response to the same old questions but as an insistence on his part to convince people that it's true.

Leung trusts Wong Kar Wai implicitly, he says, and not just because he has been working with him for 15 years. "I love his way of making movies," Leung says, "and we've known each other for quite some time, staring with 'Days of Being Wild.' We've built a lot of trust in each other, and that's the most important thing." He also acknowledges that his working relationship with Wong is different from the one he forges with other directors. "We are very strange. We seldom talk on the set. We don't see each other, besides work. And he never tells me anything about his personal life -- although I tell him a lot about mine," Leung says with a glimmer of mischievousness. "I think he needs to know, if he's going to shoot me. But he never tells me anything about himself. So for me, he's quite a mysterious person. But as working partners, we are quite happy working together."

Even so, Leung has no reservations about the difficulties and frustrations of working with Wong. He recalls showing up on the set the first day and having Wong tell him that he wanted him to play the same character he played in "In the Mood for Love," but in a different way: "Like a new man, a new character, but with the same name and same identity, but like somebody else."

Leung says he didn't question Wong's directive, because he had no idea what the story was about. "But it's very difficult for an actor to do that. I had already gotten used to the origin of Mr. Chow, his body language, his gestures, his tempo, his voice. So it was really difficult. That's why on the first day I asked Kar Wai if I could have a mustache -- to make myself believe I'm somebody else. At least I'd have something to hold on to." Wong refused at first, but Leung insisted -- he felt he couldn't find his way into the role without it. And visually as well as emotionally, his instincts were on target: Mr. Chow's pencil mustache gives him an oily elegance; it's a sliver of a symbol that defines the difference between the old Mr. Chow and this new one, whom Leung refers to as "dark and mean," a "cynical playboy."

And yet, even playing this new and rather cruel Mr. Chow, Leung doesn't completely submerge his vulnerability. It would be impossible to do so, and when you see him in person, you understand why. Leung is a decidedly masculine presence on-screen and off, but in front of the camera, in particular, there's also an alluring softness about him -- his masculinity is defined not by macho posturing but by pure comfort within his own body. You can see this in the way he moves in "In the Mood for Love": Even though Mr. Chow walks with his hands placidly at his sides -- the mark of a man who, you'd assume, is constantly afraid of making the wrong move -- his gait is assured and steady, hinting at a bold, if underplayed, sexuality that's anything but businesslike.

But even that's nothing compared with the muted expressiveness of Leung's face. In "Infernal Affairs," Leung plays an undercover cop who has all but erased his identity for the sake of his job. He reveals shadowy, playful traces of the person he used to be to the psychiatrist who's been assigned to treat him: He has a small crush on her, but it's the sort of charming infatuation that dances beneath the surface. We get an even more intensified sense of his anguish when he runs into an old girlfriend, out walking with her young daughter (who, we realize in a deftly played moment, is actually his child). He and the woman chat, filling the awkward space between them with useless words.

Leung's eyes betray everything and nothing: Other actors may seem most vital when they're playing "happy" or "funny," but Leung's velvet-brown eyes can telegraph whole chapters of feeling with a single glance -- even their despair twinkles with life. His smile is easy but sly, and it usually seems to take its cues from his eyebrows: In "Chungking Express," where he plays a cop pining for the haughty flight attendant who has ditched him, we first catch sight of him walking his beat, his peaked policeman's cap perched low over his eyes. He looks only vaguely movie-star handsome, until the hat comes off. Then his whole face opens up, and the eyebrows are the key. Quizzical, worried, vaguely amused: They speak a shorthand of their own, even when the rest of his face appears to be giving away nothing.

I studied Tony Leung's eyebrows intently in the 15-plus-15 minutes I had with him, and I can attest to their almost mystical properties. I'm deeply embarrassed to admit that, very early in the interview, I started to ask Leung a question about "In the Mood for Love" -- a picture I adore -- only to realize I couldn't for the life of me remember its title. I riffled through every secret hiding place in my brain for the correct arrangement of words, but it was nowhere to be found. This mortifying blip lasted for an interminable 20 seconds or so (although the stumbling, stupid silence on the interview tape seems to go on for 20 minutes), after which I had the good sense to make a complete moron of myself by consulting the IMDb printout I'd brought with me.

It's funny, but up to that point I hadn't thought I was nervous at all, even though I've loved Leung's work since I first saw him (in "Hard-Boiled") more than 10 years ago. He's a megastar in Asia, and a megastar to me: I would probably have been more nervous talking to, say, Cary Grant, but perhaps not much more. I realized that by not seeming like a movie star, Leung had completely disarmed me. If I were a camera, I'd know just what to make of Leung's face. But because I'm only a person, the best I can do is search it as if it were a kind of emotional map, and marvel at the inadequacy of words to describe what I see there.

Shares