Sometimes you look at a movie adaptation of a classic book and it's as if you're reading it with the filmmaker, turning the pages together. Roman Polanski's "Oliver Twist" takes the useless question of whether reading is "better" than moviegoing and renders it academic: This is that rare movie version of a great novel in which watching is reading.

Dickens' novel about a gentle-spirited orphan who's failed at every turn by the system set up to protect him is an indictment of the barbarism that thrives beneath the veneer of the most civilized societies; it's also a long, anguished wail over the willful ignorance and selfishness of us wretched humans, who were supposedly created in God's image but rarely live up to the honor. "Oliver Twist" would be a dreadfully moralistic book if it weren't such a deeply pained one, and Polanski is fully in tune with both its anger and its cruel beauty. This story hasn't been so much adapted for the screen as absorbed into it, and the biographical implications of that are unnerving: Could anyone understand "Oliver Twist" better than a Polish Jew who spent his childhood outrunning the Nazis?

The picture has a melancholy glow to it, like the pearly, diffuse light cast by a full moon on a hazy night. In the movie's brutally poetic climax Polanski actually shows us a moon like that, both an accusatory witness and a soothing presence, and for a moment we wonder if we're dreaming it. This is a picture that so sensitizes us to human suffering that even looking at the moon hurts.

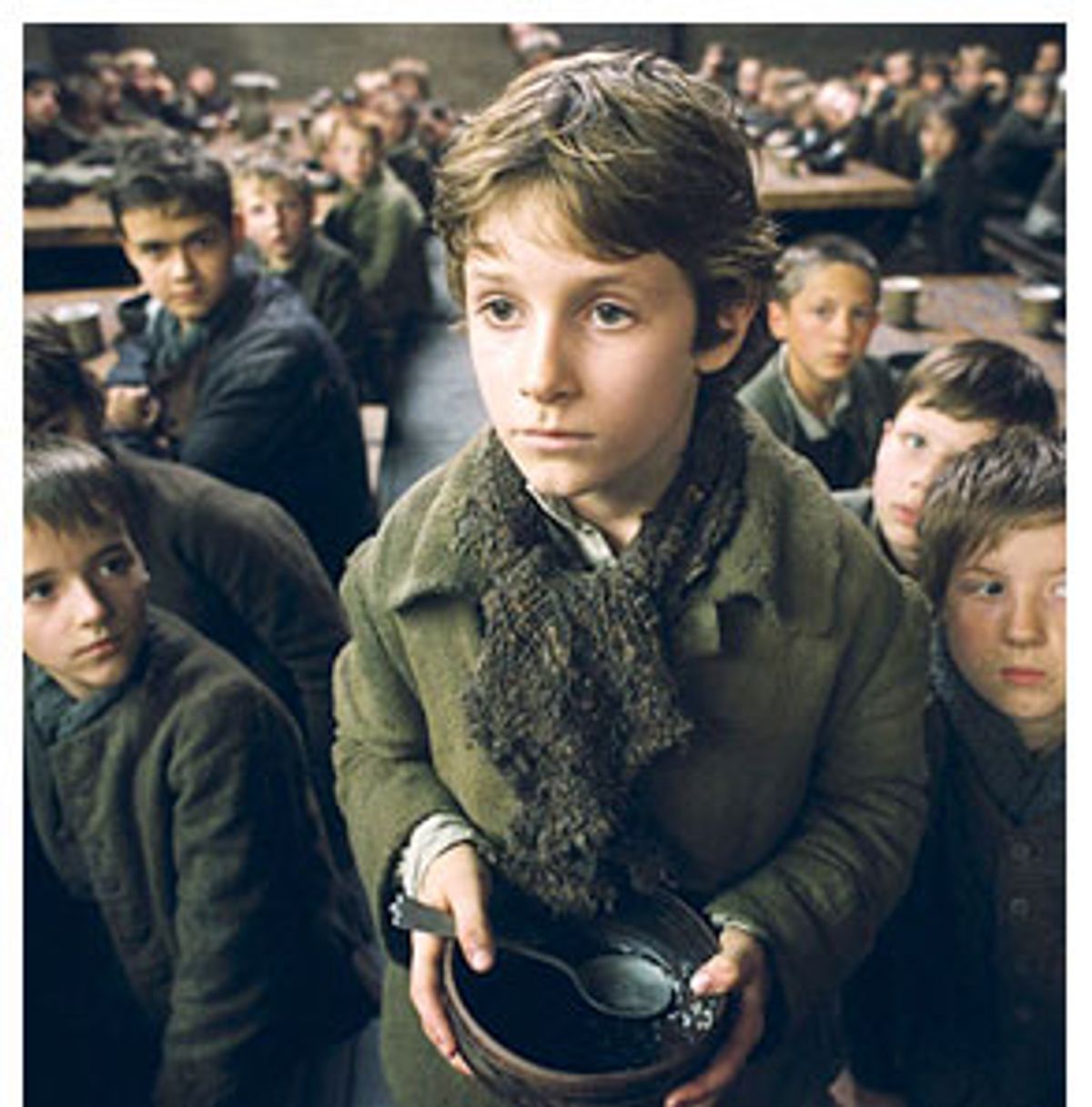

Polanski opens his movie with an engraving of the English countryside, one that gradually transforms itself into a black-and-white image and then into color -- dusty brown tones more bleak than black-and-white could ever be. A large man, the beadle, Mr. Bumble (Jeremy Swift), and a small boy, Oliver (Barney Clark), walk through this landscape, headed toward Oliver's uncertain future. Born in a workhouse (his mother died in childbirth), he's now 9 years old and the authorities have to find a use for him. He appears before the workhouse board members, one of whom asks him, "Do you pray for those who feed you and take care of you, like a Christian?" even though we can see by his fragile, bony frame that no one has been taking care of him at all.

Oliver is almost sold to a villainous chimney sweep (although sold isn't the right word, as the state would have offered the man 5 pounds to take Oliver off its hands), and spends a brief time as an undertaker's apprentice. But Oliver's future has been foreordained by the people who are supposed to care for him -- "Mark my words, you'll see him hang, it can't be too soon," they say -- not because of anything inherent in his nature, but because in their small-mindedness they can't imagine any other fate for him. To wish him dead is easier than wishing him invisible.

So Oliver runs away and finds a home with people who, at the very least, actually see him. Polanski has put Ben Kingsley in the role of Fagin, the twisted old schemer who supports a coterie of boys (and a few girls) to pick pockets for him, and who assumes a complicated, conflicted role as both Oliver's protector and betrayer. And while Dickens refers to Fagin as "The Jew," neither his Fagin, nor Polanski's and Kinglsey's, is so easily -- or comfortably -- reduced to the single note of anti-Semitism. (Polanski also takes care to note how Dickens repeatedly uses the word "Christian" with such bitter irony, suggesting that denominational affiliations carry far less weight with the author than human behavior does.)

If Polanski, who's seen the poisonousness of anti-Semitism in his lifetime, can find compassion in Dickens' depiction of Fagin, how can we find fault with it? Polanski and Kingsley give Fagin a reading that runs deep: He's a crook and a homemaker, a nurturer and a potential murderer, a manipulator and a father figure who knows the value of a kind word. And unlike the upstanding citizens of the story -- the officials who congratulate themselves on how much good they've done for Oliver and his kind -- Fagin at least knows what he's lost. The tragedy of Fagin, particularly as Kingsley plays him, is that he knows what decency is -- possibly because he used to have it himself.

Dickens is one of the most cinematic novelists, not just because of his killer plots (although those certainly don't hurt), but because he's so alive to faces. Even when he doesn't describe physical characteristics, or tip us off with illustrative names like "Mrs. Sowerberry" or "Mr. Bumble," we know exactly what his characters look like: Their faces are maps of the lives they've lived. Polanski has cast this "Oliver Twist" so carefully that he could have made a decent picture just by putting his actors in front of the camera: Clark's Oliver is subtly expressive (without committing the child-actor transgression of being too expressive), and he has the face of a Victorian engraving -- you can almost see the crosshatching of care and woe in it, but his sturdy spirit shines through, too.

The vicious thief Bill Sikes (played by the astonishing, nightmare-inducing Jamie Foreman) is a walking snarl, a hulking creature whose humanity has shrunk inside him to the size of a small, cold pebble. Pickpocket John Dawkins, better known as the Artful Dodger, is a prankster who takes life one pocket watch at a time, but there's also a sharp moral intelligence behind his impishness. (The actor who plays him, Harry Eden, has a face like a baby Harvey Keitel.)

And Kingsley's face here, a maze of prosthetic warts and wrinkles, is like a navigational chart for a lost sea. He's a figure of horror, holding a pair of tinsnips to Oliver's face when he thinks the boy has gotten a gander at his hidden treasure, or maliciously engineering a trade-off that will save his skin at Oliver's expense. Whatever goodness there is in Fagin leaks out through the crevices of his cruelty, yet it's unmistakable, and heart-rending. In one scene, Fagin trains Oliver to procure silk handkerchiefs from gentlemen's pockets, applauding the boy when he manages to take one off Fagin's person without detection. The look on Clark's face, when he hears those words of praise, is wrenching: For the first time, it has the bright glow of potential happiness.

But then the camera turns to Fagin's face, as he urges Oliver to learn from the other boys, particularly the Dodger. He tells Oliver that if he does so, he'll be headed for great things: "You'll be the greatest man of the time," he says, his eyes clouding visibly, his voice softening to a tender croak. We realize he sees the same qualities in Oliver that we do (his purity of heart, not merely his knack for thievery), and we also see that he's envisioning some dream he once had for himself, long ago.

And beneath it all, Polanski just shows so much love for "Oliver Twist" as a story. (After an opening that's faithful to the book almost note by note, he and his screenwriter, Ronald Harwood, take some liberties by streamlining the intricate coincidences of Dickens' plot, but the story doesn't suffer.) Polanski grasps the joyousness of the story (Fagin's lair is a pretty cheerful place), while bringing a chilling gravity to the picture's pivotal scenes -- most notably the murder of Nancy (Leanne Rowe), the self-possessed trollop who risks her life to protect Oliver. And in one of the movie's loveliest vignettes, the wonderful English actress Liz Smith appears as an old country woman who shows Oliver a few bits of kindness that mean the world to him: When he tells her he's going to London, her mouth makes the shape of an "O" -- it's a place as fear-inducing and foreign to her as it is to him.

"Oliver Twist" is sometimes treated as just a staple of Victoriana, but it still feels connected with the world. For one thing, the social barbarism Dickens was so attuned to isn't a relic. (Think how it took Katrina to remind us of the existence of our own "hidden" poor.) And as a meditation on both the cruelty of human beings and the decency they're capable of, "Oliver Twist" is the perfect canvas for Polanski. The movie's final scene, in which Oliver shows compassion for a man who would have delivered him to a murderer, is both a horrific miniature and a benediction. In his long career, Polanski has given us great pictures and strange, imperfect ones. Maybe that's the curse of a man who sees both sides of the moon at once.

Shares