People who have no interest in graphic novels often think the people who love them are nuts, and vice versa. But every once in a while, there's a book -- or a set of books -- potent enough to close the gap between the people who read "comics" and the people who don't. Marjane Satrapi's graphic memoirs, "Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood" and "Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return" -- released, respectively, in 2003 and 2004 -- fit that description. Satrapi, a Paris-based illustrator and cartoonist, was born in Rasht, Iran, in 1969. The "Persepolis" books recount her childhood first in pre-revolutionary Iran and then under the repressive fundamentalist regime; her teenage years as a student in Vienna, Austria, where her parents sent her after they began to fear their outspoken, free-spirited daughter might find herself in danger at home; her return to Iran in early adulthood; and, finally, her painful reckoning with the fact that it's possible to both love your homeland and find yourself utterly unable to live in it.

The "Persepolis" books are drawn in a deceptively simple, stark style, all in black-and-white: They're captivating and elegant in their austerity, like Japanese woodcuts. But they also radiate warmth and humor, even when they're used to tell stories that are often very painful. I fully expected the "Persepolis" books to translate well to the movie screen. And yet the new movie adaptation of "Persepolis" exceeded my expectations. The animated picture, in French with English subtitles, is a concise condensation of the two books that never feels rushed or unduly truncated. It's intimate, as an autobiography ought to be, but co-directors Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud also manage to give it a panoramic scale: While the movie doesn't attempt to be an Iranian history lesson, it does capture the way people's lives can be both drastically changed and yet, in some ways, remain defiantly unchanged when their government subverts everything they believe in, using God -- or some version of God -- as its chief weapon.

"Persepolis" pulls off something that's not easy for any film, even a live-action one, to do: It gives us a sense of how a kids'-eye view of the world -- particularly the way kids are capable of grasping the idea of injustice, even when more delicate political arguments are beyond their reach -- can emerge and grow into an adult sensibility. Young Marjane (her voice, as both a girl and an adult, is that of Chiara Mastroianni), circa 1978, just before the Islamic revolution, is a precocious but basically normal kid who wears Adidas sneakers and loves Bruce Lee. With her almond eyes and her ebony flip hairdo, she's a bright, elfin presence, a kid who's always asking questions and spouting opinions, borrowed from her elders, that she doesn't quite understand. Her mother and father, Tadji and Ebi (voiced, respectively, by Catherine Deneuve, Mastroianni's mother in real life, and Simon Abkarian), are politically active intellectuals. Marjane is deeply influenced by their ideas of what's right and wrong for their country, and of what's right and wrong, period: Like many kids who've been brought up to believe in God, she talks to him nightly. After she tries (unsuccessfully, thank goodness) to attack a schoolmate whose father is reportedly a member of the shah's secret police, God appears to her on a swirly cloud (how is it that kids the world over almost unfailingly see God standing on the same puffy, ethereal area rug?), explaining to her that it's his job, not hers, to mete out justice. Her job is to forgive. Later, when Marjane confronts the kid to sanctimoniously offer her forgiveness, he retorts that his dad is great because he's killed communists and communists are evil -- so much for forgiveness as an easy solution.

"Persepolis" is filled with those kinds of difficult questions and their uneasy answers. Marjane's story is all about the push-pull of trying to live your life in a meaningful way when the world is going haywire around you. One of the most moving sections of the movie addresses her devotion to her Uncle Anoosh, a former political prisoner who comes to stay briefly with the family: He gives her a swan made out of bread that he made during his imprisonment. The movie (like the books) are filled with small details that, pieced together, convey the texture of a life: When wearing the veil in public becomes a requirement by law, Marjane (as well as her mother and grandmother) reluctantly comply. And even beyond those restrictions, other small horrors mount: During the Iran-Iraq war, young schoolboys are given plastic keys, which, they're told, will get them into heaven if they die fighting for their country. (They've been told there will be girls there -- a sure a way of luring horny teenage boys into martyrdom.)

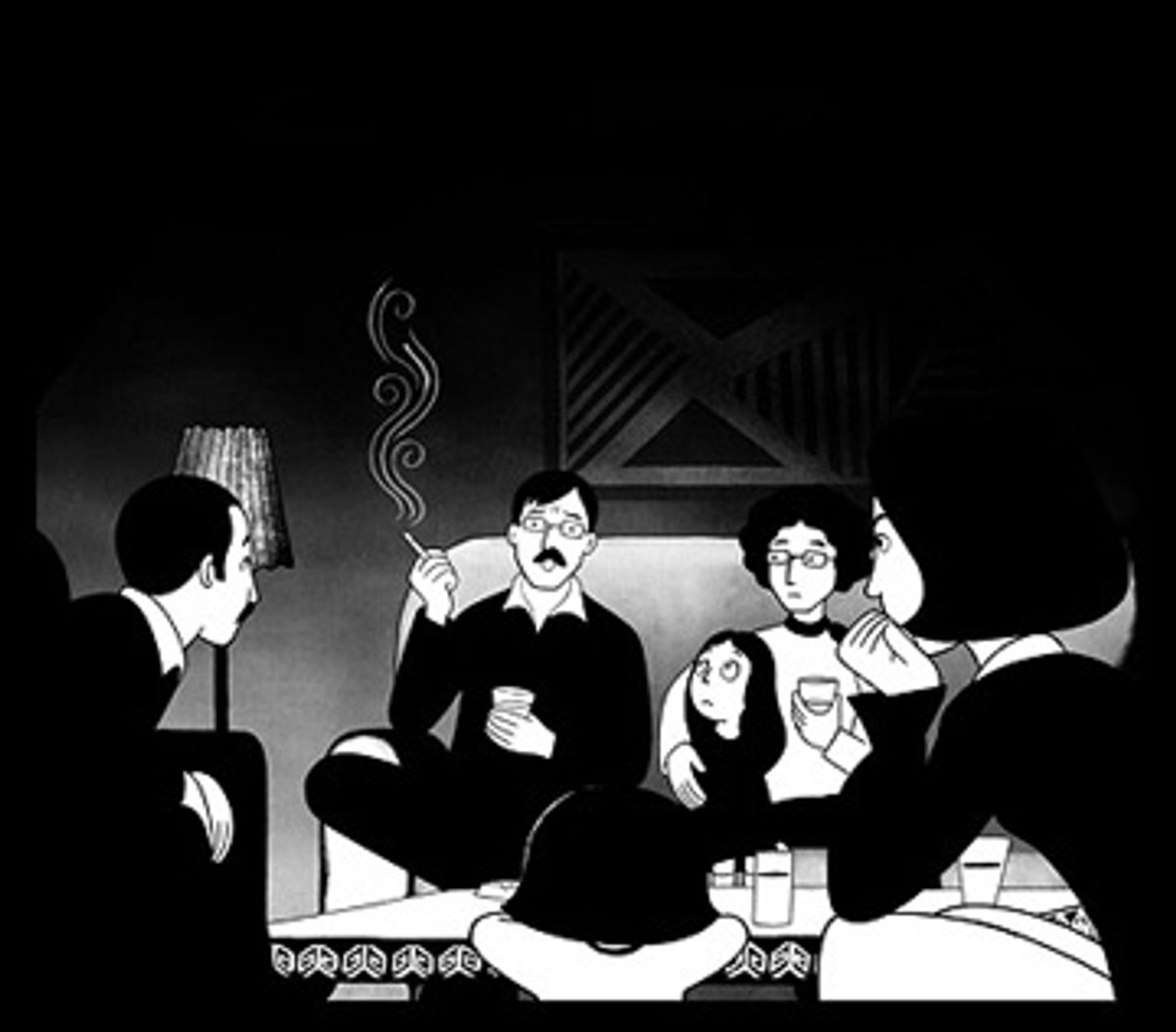

This is a world in which celebrations and parties are banned but people manage to have them anyway -- breaking the rules is the only thing that allows them to enjoy life. Marjane's principles, as confident as she is that she's always right, aren't unshakeable, either: At one point, she angers her beloved grandmother, a stout, lively woman with refreshingly progressive views about life and love (her voice belongs to Danielle Darrieux), when she recounts how she saved herself from being arrested during a raid (she was wearing makeup, which is forbidden) by telling a police officer that a stranger on the street had looked at her salaciously.

Marjane thinks it's funny that she got the man arrested; her grandmother, repulsed by the fact that Marjane has used her sex -- the very thing the government is trying so hard to control -- as an excuse, a manipulation, is furious with her. (She also reminds Marjane how many of her own relatives have been imprisoned, and even killed, for standing up for their beliefs.) "Persepolis" is a story whose heroine is often on the wrong track, which is precisely what makes it so powerful. The repressiveness Marjane grew up with is foreign, even exotic, to Westerners. But "Persepolis" is all about the ways people find to get on with life, even when their governments work hard to prevent them from doing so. It's also, quite simply, a resonant and universal story about coming of age. This is a sturdily poetic movie, rendering in black-and-white a world where nothing ever is.

Shares