About midway through Denzel Washington's new film "The Great Debaters" comes a raw and terrifying scene that exemplifies why the movie's worth seeing, despite its hackneyed and awkward story. It's the mid-1930s in rural east Texas. James Farmer Sr. (played by Forest Whitaker), a classical and scriptural scholar who was the first African-American to receive a Ph.D. from Boston University, is driving along a dirt road with his family. Distracted by some children along the roadside -- who are excited to see such a nice car, let alone a car driven by a Negro -- Farmer accidentally kills a hog that has wandered into the road.

The hog belongs to a white farmer, a man decidedly poorer and vastly less educated than Farmer, and at one stroke the ominous racial reality of the Jim Crow South comes into focus, even for one of its most respected and successful black residents. On one hand, of course Farmer has inflicted an injury on this man, depriving him of an important piece of property. But that human and economic reality nearly vanishes before the fact that Farmer, his attractive wife and their shy teenage son are alone in the middle of nowhere, facing pissed-off white people with guns.

This well-dressed college professor -- a "town nigger," as one of the white men puts it -- must shuck and jive, must "yessuh" and "nossuh" a couple of overall-clad illiterates, must tolerate being addressed as "boy" and must pay a grossly inflated price for the dead hog. The penalty for doing otherwise? We don't need to spell that out. Maybe the dirt farmers would have been content to beat and rob Farmer, and maybe they'd have felt like taking it further. That would have been up to them, but no crime committed against the Farmers, from mild to vile, would ever have been investigated or prosecuted. In a situation where he has no rights, Farmer sees that it's no moment for righteous defiance.

That's not the only moment in "The Great Debaters" when the sheer terror that underlay African-American life in the South for much of the 20th century comes to the surface. Later in the film, Melvin B. Tolson (played by Washington) and his debate team from Wiley College, a small, all-black institution in Marshall, Texas, get lost on a similar country road. They come upon one of the defining institutions of Southern living: a lynching. We don't see much: a group of white men standing around quietly, illuminated by the headlights of a few cars and trucks. A disfigured body, only barely human and no longer recognizable as black or white or any other color, hanging from a tree limb above a roaring bonfire. It's enough.

I've seen many of Washington's eloquent and dignified performances over the years without quite grasping, until now, that his defining characteristic as an actor is anger. This is a raging cliché to apply to a black actor, and borderline offensive to boot. That doesn't stop it from being true. His is a controlled, inner anger, contained behind his hooded eyes and amused, superior expression, but it's anger all the same. You might almost call it contempt: As Malcolm X or Rubin "Hurricane" Carter or the corrupt Alonzo Harris of "Training Day," Washington's demeanor always suggests that he understands the way the world actually works, and one day he'll manage to pound it into our thick and stupid heads.

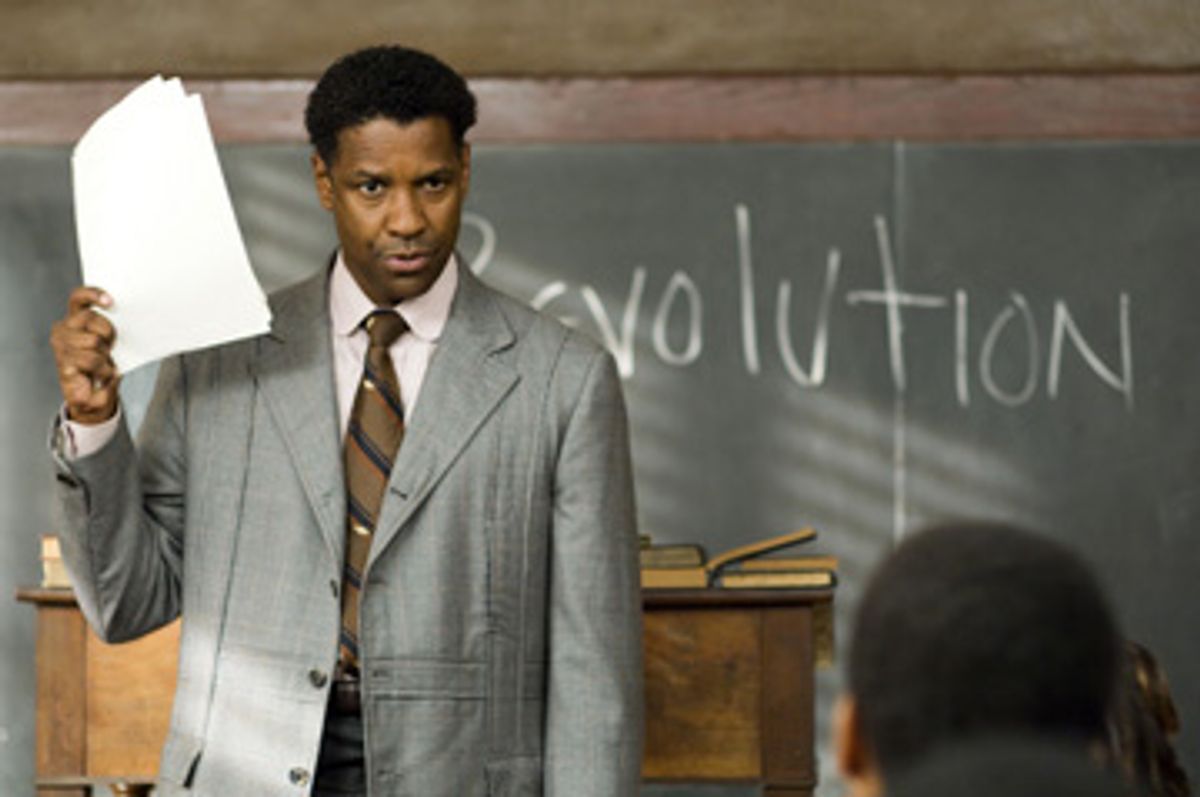

That's certainly his mode of attack as Tolson, a twitchy, standoffish man with an awkward smile and an un-Denzel-like ragged haircut, who berates, badgers and drills the Wiley debaters to excel. As seen here, Tolson resembles an intellectual version of Washington's hard-ass football coach in "Remember the Titans," but at least Washington suggests something of the man's complexity, and the film puts him back on the cultural map. Although the story of "The Great Debaters" has been heavily fictionalized (by screenwriter Robert Eisele) to fit into a standard triumph-of-the-underdogs template, Tolson is an intriguing figure in literary and cultural history.

After achieving celebrity in black America for nurturing Wiley's championship debate teams to victories over several white colleges, Tolson moved away from teaching to poetry. (Over the course of his life, he also directed theater, worked in a meatpacking plant, coached football, tennis and boxing, and served as mayor of Langston, Okla.) His writing was complex and modernist in tone, and he never got the audience or critical attention of the famous Harlem Renaissance poets. But based largely on his late, uncompleted work "Harlem Gallery," some scholars view him, in Allen Tate's phrase, as the first African-American poet to assimilate "the full poetic language of his time and, by implication, the language of the Anglo-American tradition."

As far as the actual story of "The Great Debaters" goes, I've told you almost all you need to know. It's an inspiring-schoolteacher movie, undergrad division, in which Tolson drives a motley group of students at an obscure black college to beat debate teams from elite black schools like Fisk and Howard, and then move on to the unthinkable: debating and defeating students from "Anglo-Saxon" schools. The team includes a possibly reformed lady-killer who has risen from sharecropper poverty (the handsome Nate Parker), a honey-sweet belle with high ambitions (the lovely Jurnee Smollett) and one more historical character.

James Farmer Sr., Forest Whitaker's character, was the father of James L. Farmer Jr. (played by the immensely likable young actor Denzel Whitaker, who is not related to either of his namesakes), who really was one of Tolson's debaters before going on to found the Congress of Racial Equality and a socialist student group that later became known as Students for a Democratic Society. The fact that a tiny school in the east Texas pine woods drew together two such disparate figures in African-American history testifies to the complicated quality of black intellectual life, even during the Depression, which probably marked the worst years of Jim Crow racism.

Eisele's debate scenes are almost uniformly terrible; according to his version of events, the Wiley students always conveniently argued in favor of progressive racial politics and Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal. As anyone who has actually debated knows, the real challenge comes in defending propositions you don't personally agree with. Wiley's debaters might well have been called upon to argue, say, that Southern segregation was a benefit to the Negro population, or that federal aid to the poor was immoral. And the film's culmination, a trip to Boston to debate Harvard, never happened at all. (Wiley did debate and defeat the reigning national champions in 1935, but they were from the University of Southern California.)

Washington's direction is never less than capable, and cinematographer Philippe Rousselot's images flow gracefully from scene to scene. Every scene with Washington or Whitaker in it is worth seeing, and their only extended scene together (a clash over Tolson's left-wing politics) is dynamite. But Washington's movie reminds me of Washington himself. Behind the mask of this apparently benign story about kids who beat the odds, and the birth of the birth of the birth of the civil rights movement or whatever, there's an angrier and much more interesting movie about the ugliest aspects of American history, about the classics professor and the pig farmer, about stuff that bedevils us to this day. I wish it would come out already.

Shares