Paul Thomas Anderson's "There Will Be Blood" is an austere folly, a picture so ambitious, so filled with filmmaking, that its very scale almost obscures its blankness. The source for Anderson's fifth picture is Upton Sinclair's 1927 novel "Oil!" which details how oil interests transformed the landscape of turn-of-the-century California. According to the movie's press notes, Anderson, homesick for the state in which he was born, found a copy of the novel in a London bookstore and was attracted first by its cover image and then by the story inside.

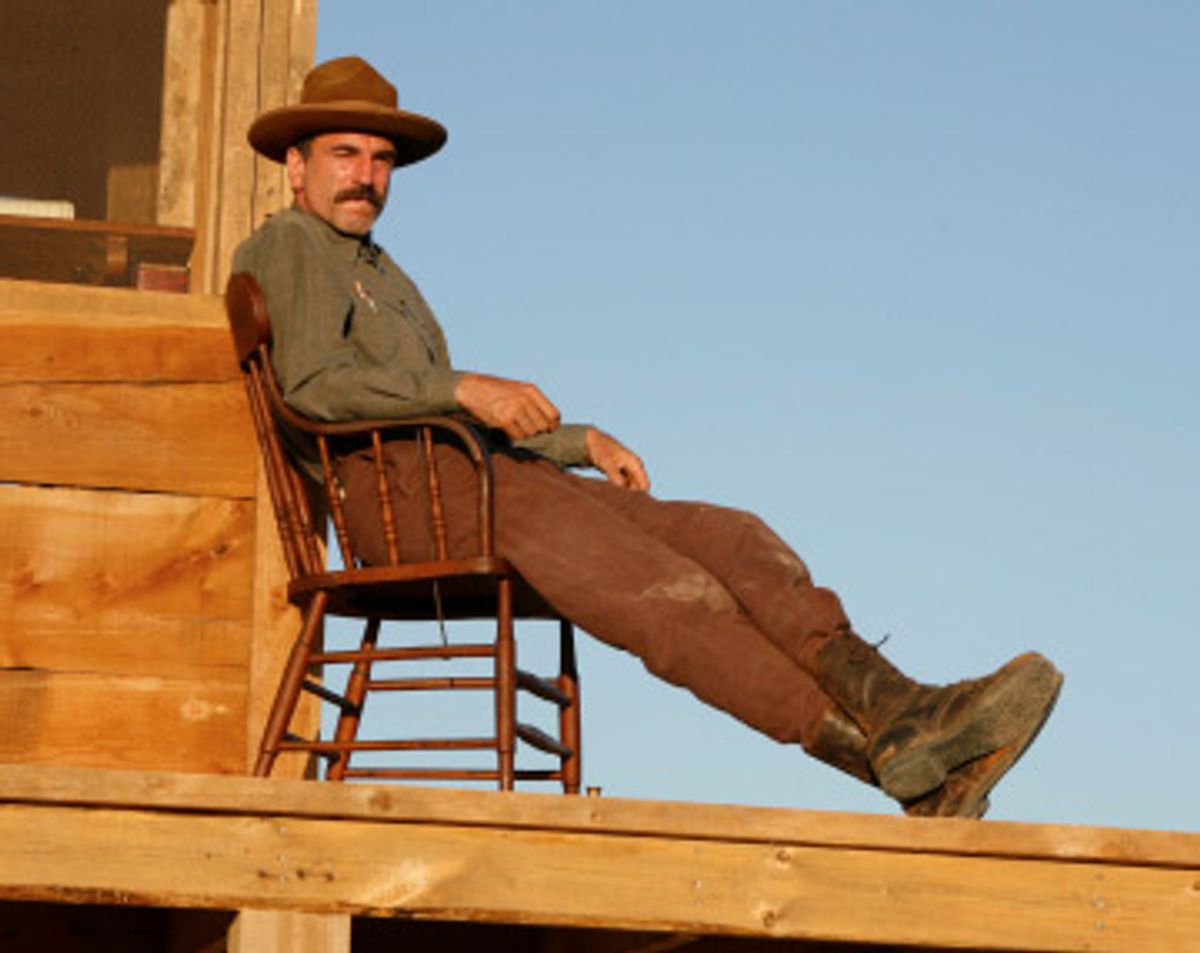

That's a lovely bit of lore, a poetic scrap of evidence of the way a book can seduce us with something as basic (and as superficial) as a cover and then draw us inside toward something deeper. Anderson -- who adapted the story himself -- may have loved "Oil!" But his love for the book doesn't burn in the picture he's made. "There Will Be Blood" is set in a suitably bleak landscape: It was shot in Marfa, Texas (the same town where "Giant" was filmed), as a stand-in for the young California, by the gifted cinematographer Robert Elswit, and his near success in turning this world of scrubby, modest bushes and blandly egotistical manmade oil derricks into something visually vital is testament to his devotion. The story -- which pits a ruthless, supposedly complex oilman named Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis) against an equally megalomaniacal man of the cloth, Eli Sunday (Paul Dano) -- has the bare bones of a potentially compelling story about the nature of greed and of faith, or about how single-minded any man can be in the pursuit of his goals. As always, the power of even a great story depends on how you tell it.

And the telling is where Anderson and his actors fail. I wanted to love "There Will Be Blood," and I tried to, twice: Of all the young, or youngish, filmmakers working today, Anderson isn't the one who's shown the most promise -- he's the one who's delivered on promises he never even had to make. When he was just starting out as a filmmaker, Anderson dispensed with the usual coughing preamble; the assured understatement of his first picture, "Hard Eight," was enough to make you take notice. Instead of beginning his career by making a flawed movie or two that made you murmur, "Someday, this guy could be something," he burst through the gate as a filmmaker who valued emotional directness over mere flash. His movies haven't been perfect, but for the most part, they've been perfectly open. Echoing the stammering-confident boast of Warren Beatty's John McCabe in "McCabe and Mrs. Miller," the greatest film made by Anderson's spiritual predecessor, Robert Altman, Anderson said from the start, "I got poetry in me," and wasted no time proving it.

Some early reviews of "There Will Be Blood" have compared Anderson to Ford and Griffith, comparisons that are extremely flattering to a young director. But it's a bad idea to drape Anderson with the heavy mantle of that kind of greatness so early in his career, when his energy, his extraordinary rapport with actors, his willingness to take chances (even to the point of adapting long-forgotten American novels) are the strengths he should be grooving on. Anderson has already made a real epic with emotion, rather than might, on its side, in "Magnolia." An epic stands or falls on the strength of its emotional details, and by that measure, "There Will Be Blood," sprawling and grand as it tries to be, fails. "There Will Be Blood" only pretends to be elemental and raw: It's really tempered and wrought, to the point of dullness. It rings with false humility, something I never thought I'd see in an Anderson picture.

Day-Lewis' Daniel Plainview is a man whose unknowability is the point, which Anderson telegraphs in the movie's opening, a nearly wordless sequence showing us how Plainview, the future oil tycoon, began extracting his riches from the earth the hard way. The sequence is beautifully shot -- parts of it are boldly underlit so we're able to catch only glimpses of a character's movement in soft arcs of bluish light, a striking effect -- and it tells us more about the persistence and hardiness of Plainview's character than the movie's remaining two and a half hours do. We see him first as a young man, scrabbling inside a rocky hole in pursuit of a single rock speckled with silver; later, he seeks a more valuable commodity, oil, and the day he strikes it is also the day he becomes a father. With his son, H.W. (played by a marvelous child actor named Dillon Freasier, whose face offers more unvarnished expressiveness than anything else in the movie), as mascot and business partner, Plainview goes about building his empire, well by well. One day a stranger whose face has the bland flatness of a china plate steps into his office with a hot tip. The young man's name is Paul Sunday (Paul Dano), and he wants to alert Plainview, for a price, to a tract of land that he knows is rich with oil, his father's ranch.

Plainview investigates the site and moves in on it quickly: The father, Abel Sunday (David Willis), is no obstacle. But his other son, Eli (also played by Paul Dano), is a wanna-be preacher with grand plans to build his own church. He wants to squeeze as much money as possible out of Plainview -- the better to do God's work, of course -- and the two engage in a wary, tortured dance that's supposed to lead us to an understanding of their similarities, their differences, and the ways in which the pursuit of their respective goals is part of this flawed but remarkable entity we call the American character.

Those are grand intentions, and the movie that's banked around them never lets us forget how grand they are. There are epic impulses everywhere you look in "There Will Be Blood"; what's missing is character development, focused storytelling and, most significantly (apart from that terrific opening sequence), any sense of raw, intuitive drama. An epic has to expand as it proceeds; this one narrows. The movie has eloquence but no guts. Its vigor is the arty kind, and over and over again it raises questions and then acts as if the answers -- or even the questions those initial questions lead to -- are unimportant: When we first see Eli -- who of course looks like Paul, because the two are played by the same actor -- we wonder if maybe they're the same person, a split personality. Later, we find out the truth, but it's revealed as if it were an afterthought, a magic wand that's waved vaguely in front of us to get us to think about the dual nature of good and evil and all that rot.

The tragedy of "There Will Be Blood" is that Anderson knows exactly what he's doing: His skill hasn't disappeared or been submerged. There are a few scenes that are so economical and yet so filled with feeling that they point a way to the wholly different movie Anderson might have made: In one of these scenes, H.W. tells his father, with a directness that's deeply touching, that the youngest girl in the Sunday family, Mary, whom he's befriended (she's played by Sydney McCallister), is beaten by her father when she doesn't pray. This clearly distresses the boy, and in the terse shorthand that Plainview and H.W. use to express their love for each other -- the kind of private language that often springs up between family members -- Plainview asks him, "Mary, she's the smaller one?" to which he responds plainly, "Yes, she is."

That scene has so much dignity that it dwarfs the flashier scenes -- particularly the overplayed, near-screwball ending -- that come later. Over and over again, I found myself respecting Anderson's choices and yet not really responding to them. The movie's weird, insistent, fascinating score is by Johnny Greenwood, of Radiohead (it sounds as if it were written to be played not by violins but by a field of anxious cicadas), and Anderson uses it intelligently in some places and rashly in others.

But the greatest disappointment of "There Will Be Blood" is the way its actors seem to matter less than its themes. This is the first Paul Thomas Anderson movie that feels woefully underpopulated. There are no women in "There Will Be Blood" -- Plainview is apparently so fixated on oil he has zero interest in sex -- and that's fine. But their absence is never addressed; the understanding is that a world of power-hungry men is interesting by itself (which it isn't). Anderson has cast a terrific performer, the Irish actor Ciarán Hinds, as Plainview's right-hand man, yet he barely shows us Hinds' face. That's so uncharacteristic of Anderson's generosity toward actors that it's almost unfathomable. Dano (who played the disaffected brother in "Little Miss Sunshine") is allowed to overact in a way that drains power out of the movie instead of charging it.

But Day-Lewis, holder of that most dangerous title "Great Actor," is the worst offender. Day-Lewis is a great actor, as he's proved in movies like "In the Name of the Father" and "My Left Foot." But his greatness is an impediment here. It seems he's decided that naturalism is boring and that big roles demand some kind of novelty. In "There Will Be Blood," he's chosen to channel John Huston, which makes for some tortured, oddball line readings that are clearly supposed to strike us as brilliant.

In "There Will Be Blood," Day-Lewis' body language tells us more about his character than any of his line readings do: His elbows are locked at an awkward angle, and his gait is stiff and belabored, thanks to old mining injuries -- this is a man who's achieved success in defiance of his body. Late in the movie, Plainview has a telling line of dialogue: "There are times when I look at people and I see nothing worth liking." I don't see that as a cynic's line, but as a jumping-off point for exploring the more elusive qualities of what it means to be human: I'm of the school that believes disappointment in humankind is a greater sign of love for it than bland acceptance. But Day-Lewis' performance doesn't tread into that territory. Over and over again, "There Will Be Blood" drops hints about what its big ideas are supposed to be and then neatly skirts them. (The movie is based on only the first 150 pages of Sinclair's book; its ending demands that we fill in the missing chunks of the story for ourselves.) This isn't a cynical picture, just a maddeningly incomplete one. And it's too emotionally constrained to be worthy of Anderson's considerable gifts. "There Will Be Blood" strives for boldness, instead of just being bold. It doesn't cut, and it doesn't bleed.

Shares