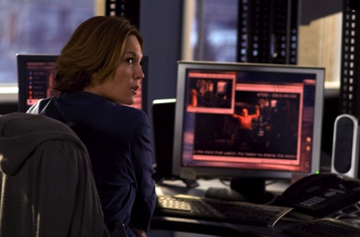

There are glints of cleverness, as well as thoughtfulness, in Gregory Hoblit’s “Untraceable,” in which Diane Lane plays an FBI agent whose specialty is cyber-crime. She’s out to trap a sicko who has set up a Web site that allows visitors to watch as a human being dies: The ingenious creep has rigged his site — it’s called “KillWithMe?” and not even cyber-geniuses can trace its source — so that the more people log on, the faster his victim dies. In other words, the killer turns Internet gawkers into accomplices: Idle curiosity is the same thing as complicity. The murderer starts small, with a kitten — he coaxes the poor creature onto a sticky trap and then, we’re led to assume, administers a shock with each successive hit. (Although the scene is staged with a reasonable amount of discretion, I still wish I hadn’t seen it.) When the deed is done, we see a grainy image of the dead animal on the left of the computer screen, while a column at the right urges viewers, with an absurd degree of jauntiness to “Join the conversation!” The comments — “Stop this now!” “Call the cops!” — suggest disapproval and outrage. But they don’t explain what these idle curiosity seekers are doing at the site in the first place.

The big ideas in “Untraceable” are fat and unmissable: At one point a character actually utters the line “We are the murder weapon,” just in case anyone out there still hasn’t gotten the point. But Hoblit and his writers (Robert Fyvolent, Mark Brinker and Allison Burnett, from a story by Fyvolent and Brinker) think their movie is deeper, and more noble, than it is. The problem is that even as “Untraceable” pretends to lecture us on our enjoyment of the suffering of our fellow humans (and animals), it can’t resist serving up its own numerous, prolonged images of torture. The kitten gets off relatively easy; the movie is set up so that we get to see, in plenty of detail, the schemes the killer cooks up for his human victims. (Those of you who enjoy sadistic surprises should skip the following sentence, but others might want to know that the murders include a slow bath in sulfuric acid and an individual’s being fried alive under heat lamps.) I guess we’re supposed to take home a valuable lesson from “Untraceable” even as we’re getting some version — a tonier, more highfalutin one — of the sadistic kicks offered by pictures like “Saw” and “Hostel.” In the end, Hoblit just wants to make sure we get our money’s worth.

“Untraceable” is a movie made of placeholders, stand-ins in for all the elements we’ve come to expect from contemporary thrillers: We have the hero (in this case, a heroine) whose dogged search for the truth unwittingly endangers her family; the psychopath who works out of his dim basement (would it kill him to buy an extra light bulb?); the lovable sidekick (played by Colin Hanks) who also, of course, needs to be endangered; and the no-foolin’-around but conveniently dimwitted boss who urges caution when it’s action that’s really needed. (Here, he’s played by Peter Lewis.)

There’s not much suspense in “Untraceable”; the picture merely taunts us with the prospect of whatever horrible thing might come next, which isn’t the same thing. The movie’s dense, plodding nature is unfortunate, because at the very least Hoblit — whose last picture was the dull, earnest thriller “Fracture” — has a capable actress as his star. Lane is fine here, but there’s little for her to grab onto in this role. At one point, a colleague urges her not to look at a dead body, knowing it will upset her. The camera shows us her face, registering not just horror but intense anguish — and then moves on to show the corpse, ravaged by the usual serial-killer shenanigans. Over and over again, Hoblit misses opportunities to make an engaging picture, instead giving us a merely pedestrian one. (It doesn’t help that the picture was shot, by Anastas Michos, in the same drab, slightly underlit brownish grays that characterize most serial-killer movies since “Seven” and “The Silence of the Lambs.”)

Why should it be so hard to use contemporary horror-movie conventions to comment on our compulsion to look? (Nimród Antal’s 2007 “Vacancy” fell into some of the same traps “Untraceable” does, inviting us to observe a victim’s suffering, but it did so with more self-awareness about our complicity, as viewers, in the equation.) “Untraceable” ultimately says less about the contemporary human condition — specifically, about the potential for the Internet to distance us from other human beings rather than draw us closer — than it does about the democracy of the Internet. “Untraceable” at least understands that the Internet is democratizing, with all the messiness inherent in any true democracy. By now we all know that the Web can foster connections between people that no one could have dreamed of 25 or 30 years ago; we also know that, at its worst, it can encourage a mob mentality. As someone who’s been writing for a Web publication for a dozen years, I know just how valuable those connections can be. But along with that openness comes the inevitable idiotic drive-by comments, and even death threats. (Yes, I’ve had them, most recently for panning “Sweeney Todd” — ah, the refined sensibility of show-tunes fans!) Accepting the democracy of the Web means wrangling with all of those things, and “Untraceable,” grim and grisly as it is, barely gets its hands dirty. If only the now-ubiquitous invitation to “Join the conversation!” came with a reminder to think before you type. But maybe that’s an idea too revolutionary for any horror movie.