Joey Ramone died Sunday. He had lymphoma, which is cancer of the body's lymphatic system. He was 49 years old.

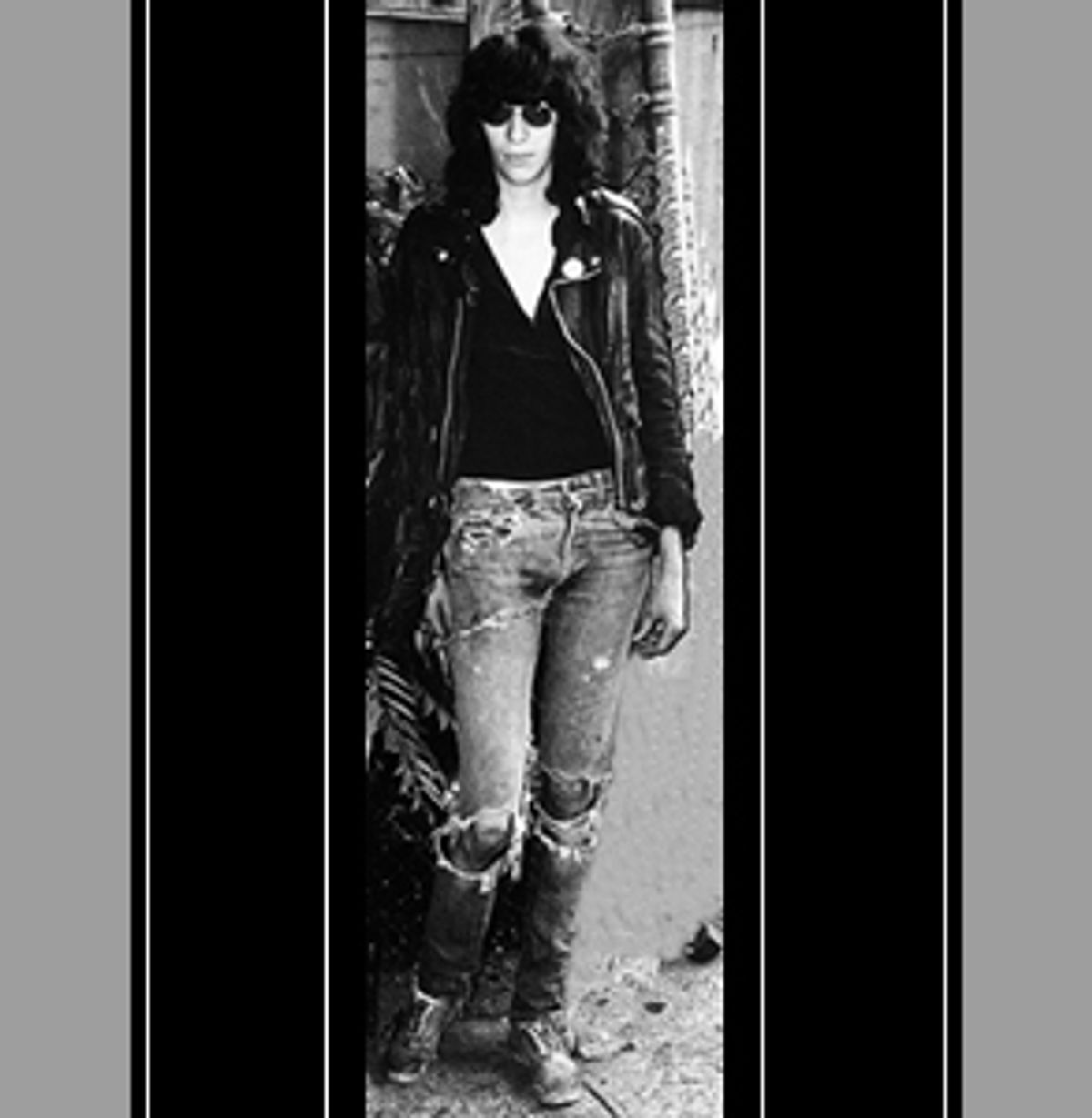

In the mid-1970s, Joey Ramone, whose real name was Jeffrey Hyman, had a disgusting mess of a head of hair and wore colored sunglasses. He was so thin he didn't seem to have a chest, a butt or knees. And he didn't sing so much as bleat.

He was a rock star.

If you were a rock-loving youth in America's dreadful Sun Belt in the mid-1970s, the Ramones gave you your first taste of what a sensation was. They didn't know how to play their instruments! Were they rock, really? They were dumb! They were Nazis!

They were an affront to everything our heroes -- Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and Bruce Springsteen -- stood for.

The band's first record, "Ramones," was a puzzle: Churning, uninterrupted guitar playing. A bass player who did nothing but hit the root note. And a singer with an impossible deadpan drawl of a voice who sang about death and drugs with virtually no nuance and could get excited only when the prospect of sniffing glue was mentioned.

It took a while, but over time it became apparent that "Ramones" was a well-disguised piece of rock criticism. (Once seen this way, in fact, it became a blisteringly didactic one.) Rock songs, the band argued, forcefully, don't need to be much longer than 1:48. They should be funny, except when they were serious. (Ramones songs were both.) The Beatles and the Beach Boys and Chuck Berry, the band lectured, were great artists, but so were the Bay City Rollers.

Three chords, Johnny Ramone, the group's guitarist, posited, were perhaps one too many.

And ballads were out.

These points raised difficult questions for a 15-year-old. The Ramones were, proudly, dumb; so why did they make us think? Why did they call themselves pinheads? Maybe ... they weren't! Maybe ... the song meant something else. Maybe ... they mean people who sing rock songs are pinheads!

Therefore, Rod Stewart is the real pinhead. Q.E.D.

When the first Ramones records were released, high school friends and I would sit in one of our rooms, huddled around the stereo. (Parents would yell if we turned it up.) We tried to parse the lyrics, the sounds, the meanings. We didn't know much about pop history, but we could sense the sendups -- "You're Gonna Kill That Girl," the title a slap at the Beatles's "You're Gonna Lose That Girl"; the indolent drawl with which Johnny sang the thing a slap at the indolent Mick Jagger.

Once we figured out the Zen of it, the world looked different. Bands like the Eagles and the Who sounded weak, Pink Floyd sounded mannered, Zeppelin almost flatulent. The Ramones seemed to understand all of that, even as they chipped chinks in the armor that would later allow for the blow that, while it did not kill the beast, made its mortality plain.

We started getting the nuances. The Ramones were an underground band playing underground music with a big-beat sound, the vocals mixed friendly and high. They weren't trying to be obscurantists or art victims; they were pop-meisters. They wanted their lyrics to be heard and wanted to have a hit single. They even wrote one. "Sheena Is a Punk Rocker" was its name, and the fact that it was laughed off the American charts is beside the point.

Soon after, the band was writing ballads, good ones. The Ramones' third and fourth albums, "Rocket to Russia" and "Road to Ruin," in their own way, are as good as, say, "Beatles VI" or "Surf's Up," take your pick, and have songs that are played, today, more than 20 years later, with surprising regularity on rock radio. And everyone knows now that the Ramones invented punk in its most ferocious form: After them came the Pistols, and the Clash, and X-Ray Spex, and Joy Division, and X, and ....

Seven or eight years after we'd first heard the Ramones, one of those same high school friends came to visit me at college. We'd both read about, but hadn't actually heard, a mysterious single the group had released in Britain -- a sonic blast of a song, it was said, called "Bonzo Goes to Bitburg." This, too, was confusing. By then we knew things about the Ramones we hadn't before: that the early Nazi imagery was just a passing idiocy, but that Johnny was a Republican who had voted for Reagan. Politics for a band this dumb was obviously a minefield.

But Joey had turned up, oddly, on the "Sun City" single, and then there was an odd track on "Too Tough to Die" called "Howling at the Moon"; if you read it right, as I think I did, you could picture a paranoid Joey railing against a nightmare onslaught of guns and corporate power: "There's no law/No law anymore/I want to steal from the rich/And give to the poor."

Odd thoughts from the Ramones. Anyway, late one night, we found the single in a Berkeley, Calif., record store -- a heavy 12-inch import that cost more than I could afford. It was after midnight when we got home, and since my roommates were asleep we were suddenly transported back a lifetime: sitting late at night, the turntable spinning, ears close to the speakers. We heard a revved-up guitar roar, then an almost Springsteenian change-up.

And then what sounded like a fucking glockenspiel.

What came next was a cry of betrayal. Disgust rose from Joey's voice as he dissected a few seconds of image on the TV news: an American president laying a wreath in a cemetery where SS officers lay buried.

They, too, were victims, the president said.

I didn't need to be told about Reagan at that time, but as we listened to Joey's pained, pleading voice, as we heard Johnny lob guitar bombs and as we were swept away by the Spectorian, rushing production, we marveled again at the Ramones' capacity to surprise.

And Joey finally found ferocity, howling his way through the group's greatest song and his greatest vocal performance. The Ramones were never as dumb as they looked, but they weren't geniuses either. But listening to Joey think his way through that particular political act in that particular song is a lesson in moral education that any of us can learn from.

Joey Ramone wasn't the band. He had Johnny, for several years at once the best and worst guitarist in the world, by his side, and a smart guy named Tommy Erdelyi playing drums and helping produce the early records.

Still, there's a legend near the tomb of architect Christopher Wren that applies to Joey Ramone as well: If you would see his works, look around you. He faced the truth where he found it and kicked a generation, hard, in the ass. I was part of that generation, and one of the things Joey Ramone taught me was that I didn't have to wait around for him to surprise me again.

Shares