In 1984 my father and I were rotating on twin axes. At age 11, everything I'd started was something that I'd quit: baseball, soccer, drawing, comic book collecting, piano, choir. My father, who'd just turned 27, had never quit anything at all, and that was starting to wear on him and everyone he knew.

When I think back on it now, it seems like we were desperate for each other. Nothing else worked. I was an awkward kid with bad hair and immense glasses, searching for some kind of identity, and he was rounding out the last days of his own extended, awkward childhood that had, I guess, gone sour long ago.

But '84 was the year all that changed. My father found a 12-step program. And I found Talking Heads and pop music that, in that era, promised nothing less than complete reinvention for nerdy, kind-of-sad kids like myself. By the time I was 13, my Dad was clean. I was strung out on rock 'n' roll.

Around the same time, after years of sporadic, heartbreaking visits, my father and I were spending every other weekend together in his tiny South Philadelphia apartment -- the kind of place you end up in only after you've been told that you have to completely rebuild your life.

Those weekends were great. They revolved around the stereo, "Saturday Night Live" and baseball cards, all of which my Dad and I endorsed with equal enthusiasm. With his program friends, he took me to see the Laurie Anderson movie "Home of the Brave," which I didn't understand at all, but gave me the feeling that I was in on the ground level of something cool. Both of us were also really into the soundtrack "The Cat People," an awful companion to a forgotten erotic thriller with one great David Bowie song ("Putting out the fire with gasoline/ Putting out the fiy-ah with gass-o-leee-eee-een!").

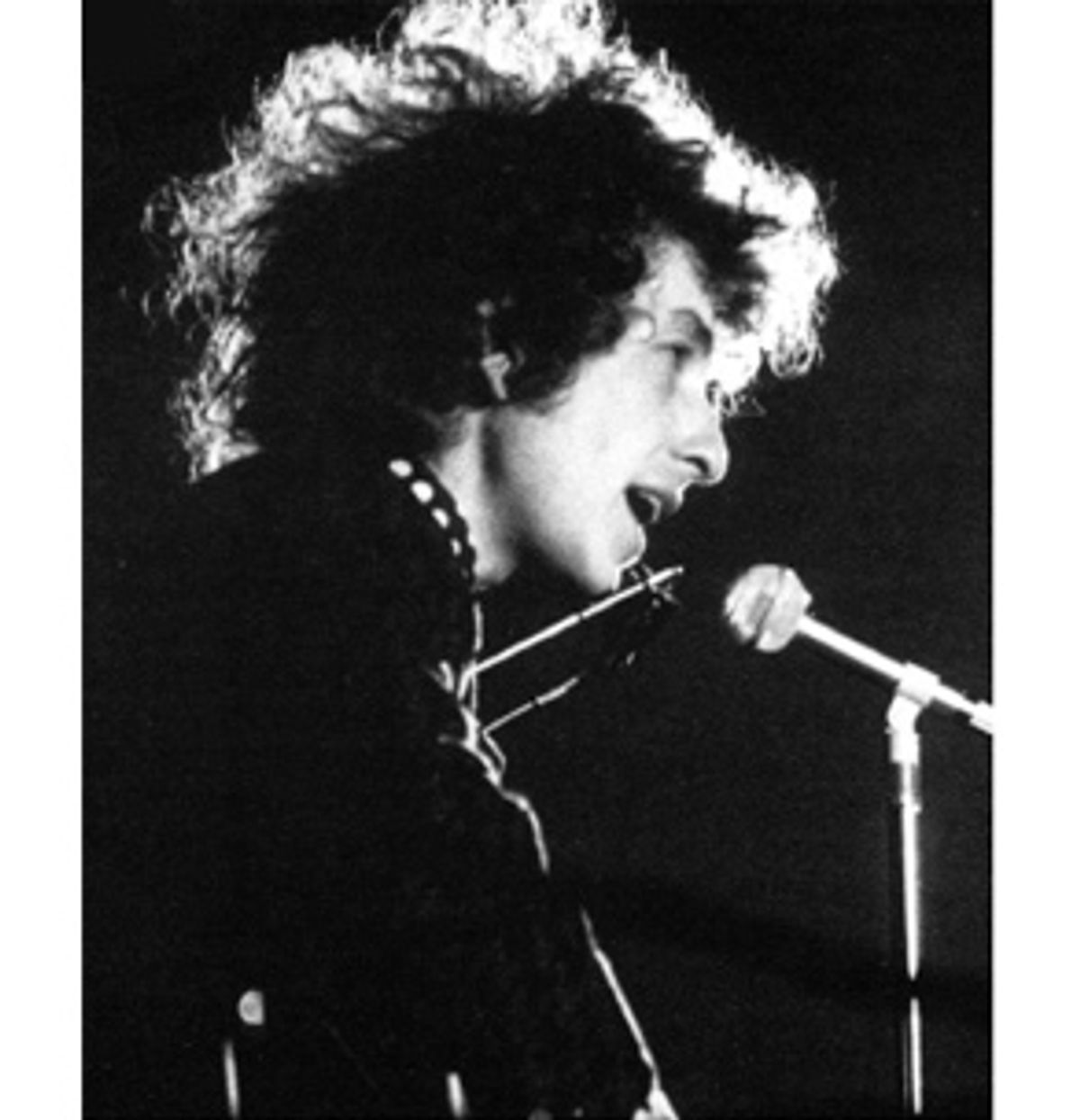

Always looming in the background were my Dad's favorite bands, like the Rolling Stones, as well as a reinvigorated passion for the life and work of Bob Dylan. For my Dad and a lot of his friends who were in recovery, Dylan embodied the kind of person who could reinvent his old, bad self and somehow stay true. At the same time, Dylan's embrace of Christian and Jewish faiths walked the same kind of humbling line these guys had been walking after every other option had plainly failed them.

But at 13 -- and on to 14 and 15 -- I thought Dylan was, in the parlance of the times, totally gay. High on new wave, I saw nothing whatsoever in the harangue-and-whine that my Dad and all his friends swore up and down was the seer, the sayer, the rock 'n' roll saint.

Seeing a rebellion coming, and thinking he could help, my not-so-old man started the push. My father sent me to Bob school.

The Christmas before, an electric guitar had appeared under the tree. I'd already spirited away my stepfather's big old Gibson, bummed $20 and gone over, once a week, to my father's best friend's house, where, week to week, Jimmy Lombard was teaching me to play his favorite songs, first "House of the Rising Sun" and later "I Don't Believe You," "Desolation Row" and "She Belongs to Me." The songs seemed archaic and strange, but I had to learn some way and Jimmy didn't know "Psycho Killer."

Later, there was a set of hand-me-down records: "The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan," "Bringing It All Back Home," "The Times They Are A-Changin'" and, leaping time, the sucking winds of "Desire." My Dad left me the vinyl, buffed up with Discwasher record cleaner, in new plastic LP bags -- like a hand-me-down Boy Scout uniform.

But this was not in the late '60s, or even in the early '70s; it was in the late '80s. While the rest of my teenage universe centered on Depeche Mode and the Smiths, my father was earnestly, slowly and with much deliberation trying to convince me that none of that, or almost none of that mattered. And because Bob Dylan's music didn't do it for me, at least at first, my Dad told me about the importance of Bob.

It went something like this: As hard and as awful as it was being a teenager in the '80s, it was even worse being Bob Dylan. Bob had weathered every criticism: for art, for religion, for the way he treated people, for "Street Legal." My father cherished Bob not so much for what he represented or what he endorsed -- or even for his music -- but for his heart and that he would follow it, stay true to it. That's what mattered.

And even though the late '80s were indeed Bob's darkest hours -- listen to "Knocked Out Loaded" and it seems as if he couldn't even get a good drum sound in those days -- my father saw Bob as a scratch-and-win-ticket sort of role model: If he scratched at the right places, steamed off some of the bad parts, he might even make a 13-year-old Tears for Fears fan aware of this man's almost all-encompassing (if, for the moment, fading) relevance to everyday life.

So that's what he did. Every Saturday and Sunday night after dinner, while my stepmother Anne Marie cleaned up, my father would take me into the living room, sit me down on the couch and take me through the finer points of even "Desire" and "Infidels" (which I still think is utterly terrible), all the way back to his boot of "The Gaslight Tapes." Hour after hour of discussions about the long, ugly sagas of Bob and Rubin "Hurricane" Carter, Bob and Carla Rotolo -- his ex-girlfriend's sister, for whom "Ballad in Plain D" was written -- and so on, delivered as Gnostic gospels, an alternate history of the '60s as a back-stabbing melee of drugs and misunderstanding.

For a teenager, especially for a teenager desperate to rebel -- who, deep down, loved his parents for all their fuckups and misfires and especially their admissions of them -- this was discouraging. Because all I had to do was look into Dylan's eyes on the cover of "Highway 61." I could tell that Robert Zimmerman had reinvented himself and stuck at it in a way that most punks just couldn't even stomach.

Weirdly enough, I learned this little lesson in rebellion from my father, who was doing some kind of hand-jive and overbite to "Maggie's Farm" in front of the living room stereo. I wasn't sure, but I didn't think that was the way rebellion was supposed to work.

On the other hand, there were the shows my father dragged me to, which -- more classic Dylan in the '80s here -- were often as transcendent and inspiring as they were boring or completely baffling. At this point, early on the Never Ending Tour, Dylan had G.E. Smith, who by my informal polling over the last 14 years or so was and remains the most hated man in all of rock 'n' roll, whether you blame that smug grimace he sported on "Saturday Night Live" or his association with Hall & Oates.

Some of those shows were grueling. After seeing "Positively Fourth Street" mangled by weird tempos and a mumbled delivery -- almost as if he didn't mean it anymore -- I swore to my father at least five times that I'd never go see Bob Dylan again. I couldn't handle one more version of the cloying, sappy "Forever Young." Dad reminded me that Dylan could quit, or die. Sometimes I just refused, and sometimes I was better off for doing so. The Dylan strikes spared me Bob Dylan with the Grateful Dead.

Among all those songs, all those shows, it's hard to tell exactly when Bob school stopped being a sort of forced, after-school catechism and turned into Bob immersion. But I remember one day when I was 16. I was at a family birthday party when everybody started pushing Jimmy Lombard and me to play guitar for them and reveal the monster Jimmy'd been creating with those guitar lessons. And after a brief conference between the two of us, we figured out that, at that point, other than a Michael Penn ditty here or a Lou Reed number there, all I knew how to play were Bob Dylan songs. So, in my reedy, cracking, way off-key tenor (which has still never completely left me), Jimmy and I entertained the family with "Queen Jane Approximately": "When your mother sends back all your invitations, and your father, to your sister, he explains ..."

For most of the clan, the acoustic racket no doubt rankled and annoyed as much as Bob himself did at Newport when he went electric. But I was electrified in another way. It was one thing to have this music playing on a stereo, a passive artistic experience, but to be singing and playing these words, these off-kilter melodies and snotty axioms, to have these things pass through you, was something else altogether. It was beautiful and sad, and at 16, I learned what Roger McGuinn and Joan Baez and Odetta and everybody else had known all those years ago: Bob Dylan is fucking awesome.

That feeling of awe and wonder and inspiration has never really gone away, and in fits and starts, it even grows. For my 25th birthday, my father -- who doesn't let up easily -- gave me the then-just-released "Time Out of Mind," widely regarded (and rightly so) as perhaps Dylan's best record since "Blood on the Tracks" (which I finally began to get into at 23). "Time Out of Mind" is a record plainly about aging and passing through and getting on, and when I listened to it in my apartment that night, I wept. I couldn't help it; that record is beautiful and funny and sad in a way that rock 'n' roll almost never is. I've been taking notes on it ever since.

This week I left with my own band for our first tour of most of the United States. I'm nervous, full of trepidation, but also proud and thankful. Had it not been for my father's insistence on his hunch that Bob had something that I desperately needed -- at that point in my life and now more than ever -- I may have never picked up a guitar. I may have never picked up a pen. I may have never seen the beauty in a put-down, or the put-down in beauty, or learned that that -- along with changing your tune, following your muse and thumbing your nose -- really is art. I have Bob to thank for that. But more than that, it makes me teary to think that my father thought well enough of me, even as a snotty teenager, that he'd share with me the art that spoke for him above almost everything else, and that, then as now, he has never given a second thought to sharing it explicitly, insistently, annoyingly. I have a 9-year-old sister now, who's already listening to Dylan in the car every day. Right now, she hates him. But she'll see.

Shares