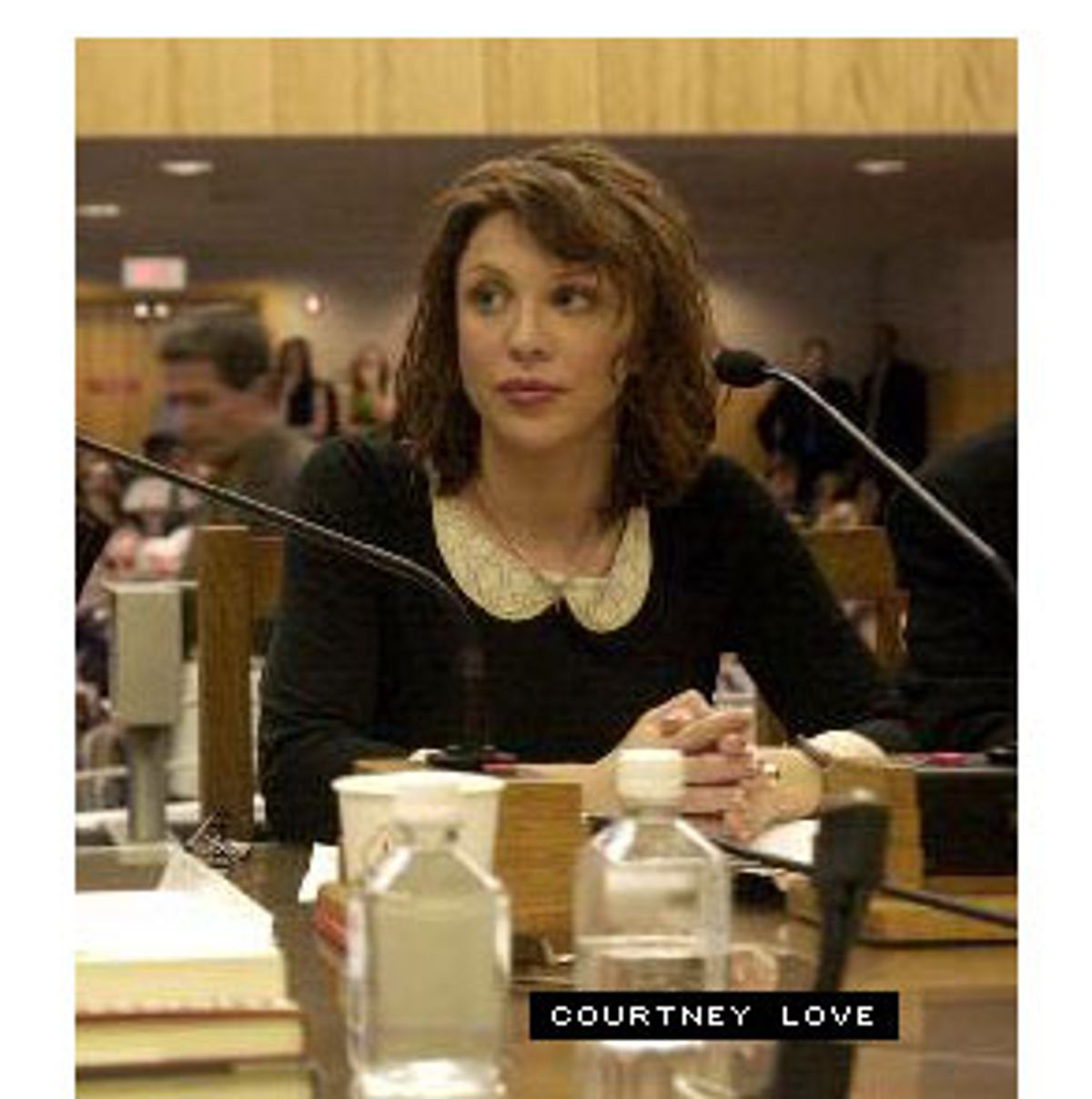

She walked into the hearing more than an hour late, with a red felt hat pushed over her eyes, looking every bit the rock star. She staggered into Committee Room 4203, in the California state Capitol, and sucked the oxygen out. The men in neckties seemed to gasp collectively. Cameras turned away mid-sentence from LeAnn Rimes, the teenage country sensation, to focus on the woman as she removed the hat, shook out a head of red-rinsed hair and took her seat next to Don Henley.

With that, Courtney Love's crusade against the record industry came to Sacramento Wednesday, in a committee room normally reserved for haggling over budget minutiae or marathon sessions on the state energy crisis. Love, alternative rock star, actress and the widow of Kurt Cobain; Henley, onetime leader of the Eagles, whose first greatest-hits set now stands as the bestselling album ever; the Dixie Chicks, who sold 11 million copies of their last album; and Rimes lent some star power to Sacramento Wednesday, as they asked the Legislature to repeal a state law that they say turns artists into "indentured servants" to the recording industry, as Henley put it.

Love was her typical ebullient self, vacillating between the articulate and the scatterbrained. When, for example, she was asked about AFTRA, the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, which serves as a sort of de facto union for some musicians, she was dismissive.

"AFTRA doesn't negotiate our interests in terms of healthcare," she responded. "I can get six days of rehab maybe ...." Love has confessed to heroin use in the past and has seen celebrity rehab from the inside. Her remarks were cut off as the room of lawyers and legislators erupted in laughter.

The informational hearing was convened by Democratic state Sen. Kevin Murray of Los Angeles, a former agent at William Morris Agency, in an effort to defuse growing tensions between record labels and their artists. At the heart of the hearing was a provision in California state law, passed in 1987, that allows record companies special dispensation to enter into contracts with artists for more than seven years. Under state law, no other industry contract for personal services can extend beyond seven years.

Henley, Love and others say the industry has manipulated those laws to lock up recording artists for their entire careers. "The deck is stacked in the labels' favor," Henley said. "Record companies can fire us, but we can't fire them."

Speaking for the labels was Miles Copeland, founder of the eclectic I.R.S. Records, home in the 1980s to then-uncommercial bands like R.E.M. Copeland contended that though the record industry grossed more than $41 billion last year, much of that becomes the millions of dollars the labels spend on acts that never make money.

"The difference of our business, unlike banking and all that, is we invest millions of dollars in artists and at the end of it if it doesn't work, they walk, we're stuck holding the bag," he said. "This is why labels have to have a length of time with their artists, so they will spend these millions and millions of dollars to make artists happen. And if major artists can simply walk out from their contracts, the record business will be in serious trouble and many, many artists who would like to have a career like Don Henley has had will never be given that opportunity. My concern is I don't want to see the health of the record industry further attacked particularly when we're seeing the Internet, which is our real danger.

"It's risk vs. profit," he said. "It's common sense. You take away profit, and you take away willingness to risk."

The labels also argue that the exception was made for the record industry because it is not unusual for big-name artists like Love and Henley to let years go by between records.

Henley and Love said successful artists should not be made to pay for the risks labels take on untested bands, and that recording companies should show more restraint before inking a band to a record deal.

"If they would sign less artists, I think everyone would be better off," Henley said. "Record companies are letting their arrogance get in the way of good business sense."

For Love, this was just the latest round in her ongoing battle with the recording industry. Peeved at lack of promotion and attention her label, DGC, gave to her band Hole's last album, "Celebrity Skin," Love refused to produce any more albums for the label. What exactly Love's "label" is provides a trenchant insight into the current state of the music industry. DGC is an offshoot of Geffen Records, now controlled by a company called the Universal Music Group, which is itself a subsidiary of the giant Vivendi Universal conglomerate, which among other things is the biggest record distributor in the world.

The label responded with a lawsuit, charging Love with breach of contract. She responded with a wide-ranging suit of her own, which among other things tried to overturn the labels' exemption from the state's seven-year personal-service law. A judge has already dismissed that part of her suit, however. Several other lines of attack are still being litigated. (Love and Henley are also trying to get the U.S. Congress to make the seven-year limit a federal law.)

Her suit is being closely watched by artists and the industry. It will be surprising if she prevails, but it does have the potential to fundamentally change the way the recording industry works.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

"Let's kill all the lawyers/Kill 'em tonight," Henley sang in a recent reunion song with the Eagles; but of course he, like many other artists, has been keeping teams of attorneys busy in recent years. Indeed, Murray said it was the increasingly litigious nature of the record industry that prompted him to call the hearings: "When I was in the music business, artists and record companies never sued each other," he said. "[It] just didn't happen. They threatened to, they yelled and screamed, they made demands, but rarely did they actually sue each other. Over the past few years, you've seen many more lawsuits on both sides."

But when asked about Love's lawsuit, Murray tried to change the subject. As he moderated the press conference before Wednesday's hearing, Murray stepped in when someone from the industry was asked to talk about what potential effect Love's lawsuit may have on the industry.

"Frankly, we're not trying to focus on any particular artist or any particular lawsuit," Murray said. When pressed about the deteriorating relationships between artists and their labels, Murray said, "I didn't say that they had deteriorating relationships, I said they were more willing to sue."

Instead, Murray wanted to focus on the particular provision of the state contract law at issue. But it's unclear what impact a change in the law might have. Most major labels have offices outside of California, where there are no seven-year laws; many in the industry assume that, if the Legislature repeals the law, labels will simply offer contracts out of their New York offices.

"We want California to be both artist friendly, and company friendly," Murray said. The line, of course, is a fine one. While artists appeal to the Legislature for remedies, the state is somewhat beholden to the entertainment industry, which has blossomed over the last decade into the largest in the state.

"What this really comes down to is control and respect," Love said. "I've made more for Universal than 'Titanic.' And are they even nice to me? No. They're rude!"

She also saved some harsh words for the Legislature, which passed the record industry's exemption in 1987. "You guys got snookered," she said. "I don't care what the RIAA tells you today, they lied to you." (The RIAA is the Record Industry Association of America, which has launched an offensive against Henley's and Love's campaigns.)

The remaining causes of action in Love's suit attack the way record-industry royalties and accounting systems are structured. Her suit also seeks to prohibit labels from selling acts to other labels without the artist's consent, a frequent occurrence as the record industry continues to consolidate. Love really wants a full-scale restructuring of how the industry works, including a push for a more active recording-artists union. "We don't have anything like [the Screen Actors Guild]," Love told the committee.

Shares