Somewhere in southwest London, at this very moment, sits a computer, the contents of which could either exonerate or condemn one of the world's biggest rock stars of perhaps the most ghastly of all media crimes: the downloading and possible redistribution of child pornography. That hard drive threatens complete ruination -- to say nothing of the consequences of Pete Townshend being proven guilty. And while the disclaimer that should run here should say that, hey, so very much is unknown, and like everyone, Pete Townshend's computer is an information bomb about himself and God only knows what might explode, as a fan, that all feels kind of gutless. And why?

Because it's my belief that Pete Townshend is innocent. Or rather, he could be. View the charges he's suspected of -- as well as his defense -- through the prism of his work, some 35 years of it, and one thing becomes clear: Pete Townshend, from the very start, has always issued reports from the sexual fringe. He's turned into pop poetry the things that we cannot help liking, and all that we disdain, as well as (perhaps most important right now) all that we doubt about ourselves, sexually, emotionally and socially.

As early as "Substitute" -- one of the Who's breakthrough singles -- Townshend had articulated a kind of muted, blushing rage about traditional sexual roles and how lots of people just don't fit into them: "I'm a substitute for another guy/ I look pretty tall but my heels are high," declared the protagonist, all too aware that he could never measure up to whatever was expected of him by society, his date or both. It just wasn't that simple. Similarly, "Pictures of Lily," one of the great Who songs (as well as probably the all-time greatest rock song about obsession and masturbation), looked very early on at a sort of modern sublimation of and guilt about sexual expression of any kind. And as much as these songs held disarming doubts about a young man's place in the (sexual) world, they were also great rock 'n' roll -- outsider tales, one and all. By the time Townshend and his mates came up with the rock opera "Tommy" -- about a deaf, dumb and blind kid molested by his uncle -- the Who were treading on the kind of terrain previously only inhabited by guys like André Gide. Heady stuff, to be sure, and making it all rock couldn't have been easy.

Or maybe it was. The greatest thing about the Who was that they were always railing against something. And sure, it might be a level of historical revisionism to say that they were marauders against sexual provincialism -- rather than the preconceived (and easier to digest) notion that they were just out to wrack the nerves of the older generation -- but go back to the music, to say nothing of Townshend's comments about it over the years, and it all checks out.

And, until we know more, so does Townshend's defense today. "On the issue of child-abuse, the climate in the press, the police, and in Government in the UK at the moment is one of a witch-hunt. This may well be the natural response triggered by cases like that of my friend who committed suicide. But I believe it is rather more a reaction to the 'freedoms' that are now available to us all to enter into the reality of a world that most of us would have to admit has hitherto been kept secret. The world of which I speak is that of the abusive paedophile. The window of 'freedom' of entry to that world is of course the internet."

That's Pete Townshend himself, in an essay he published on his Web site -- a year ago. In it, he relates the story of a friend who was abused as a child (and later committed suicide) and then he talks about child porn as both a shadow industry and a phenomenon, as well as his own childhood and his suspicions that he might have been abused as a toddler.

Like many who heard Townshend's "research defense" -- that he did indeed browse child porn on the Web a few times but that it was in the service of something he was writing -- I scoffed. Does one really need to see atrocities to be convinced of their existence? Wasn't there any other way he could have commented on the subject without diving headlong into the pedophiliac fray?

I suppose it's possible, but then again, maybe not. Pedophilia -- along with many other greater or lesser pathologies based in and around sexuality -- has a vocabulary all its own, as horrifying, disgusting and beyond the pale as it might be. Even an episode of "Law and Order" would tell you that. And perhaps, to get the impact of it, if indeed Townshend was writing about it, he wanted to see the horrors firsthand. Is that, in and of itself, shameful -- to try to confront and process an atrocity firsthand? I don't know.

But I do know this: We live in a hysterical time, one in which technology has outrun our capacity to come up with the ethics to go with it. There are elements of Townshend's dilemma that reek of McCarthy-era thought crime, where to investigate the lunatic fringe is to be suspect of sympathizing with it. Especially in this sort of neo-Puritan age where to be accused of a sex crime is, for all intents and purposes in the court of public opinion, to be declared guilty of it.

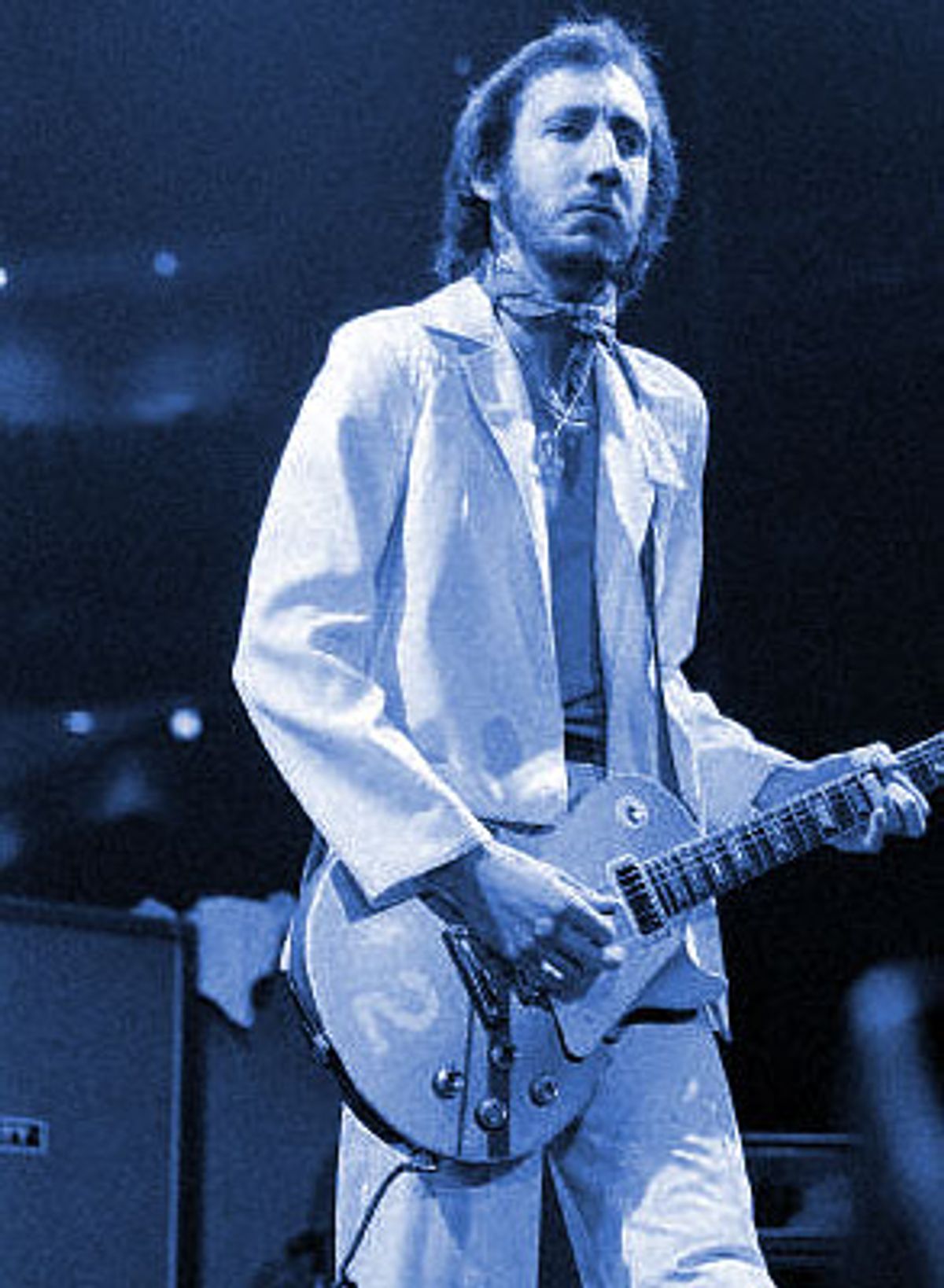

Rock stars -- just about all of them -- are given over to excess and ridiculous levels of self-indulgence. And in a way, that's what we like about them. There was a time when Pete Townshend could not take just one drink, could not do just one line, could not pen just one rock opera. But even in the throes of all this, there was something about the guy that spoke to more than just that excess and indulgence; in so many ways, Pete Townshend has always been the anti-rock star. His looks, his demeanor and his music have always suggested a sort of worldview that acknowledges the ridiculousness of his own fame and fortune; even when he has been reeling out of control -- band members dying, fans getting crushed, the lot of it -- he has known himself more than most in his station. Maybe more than any other rock star out there, he's earned something most of us don't even remember anymore: the benefit of the doubt.

Shares