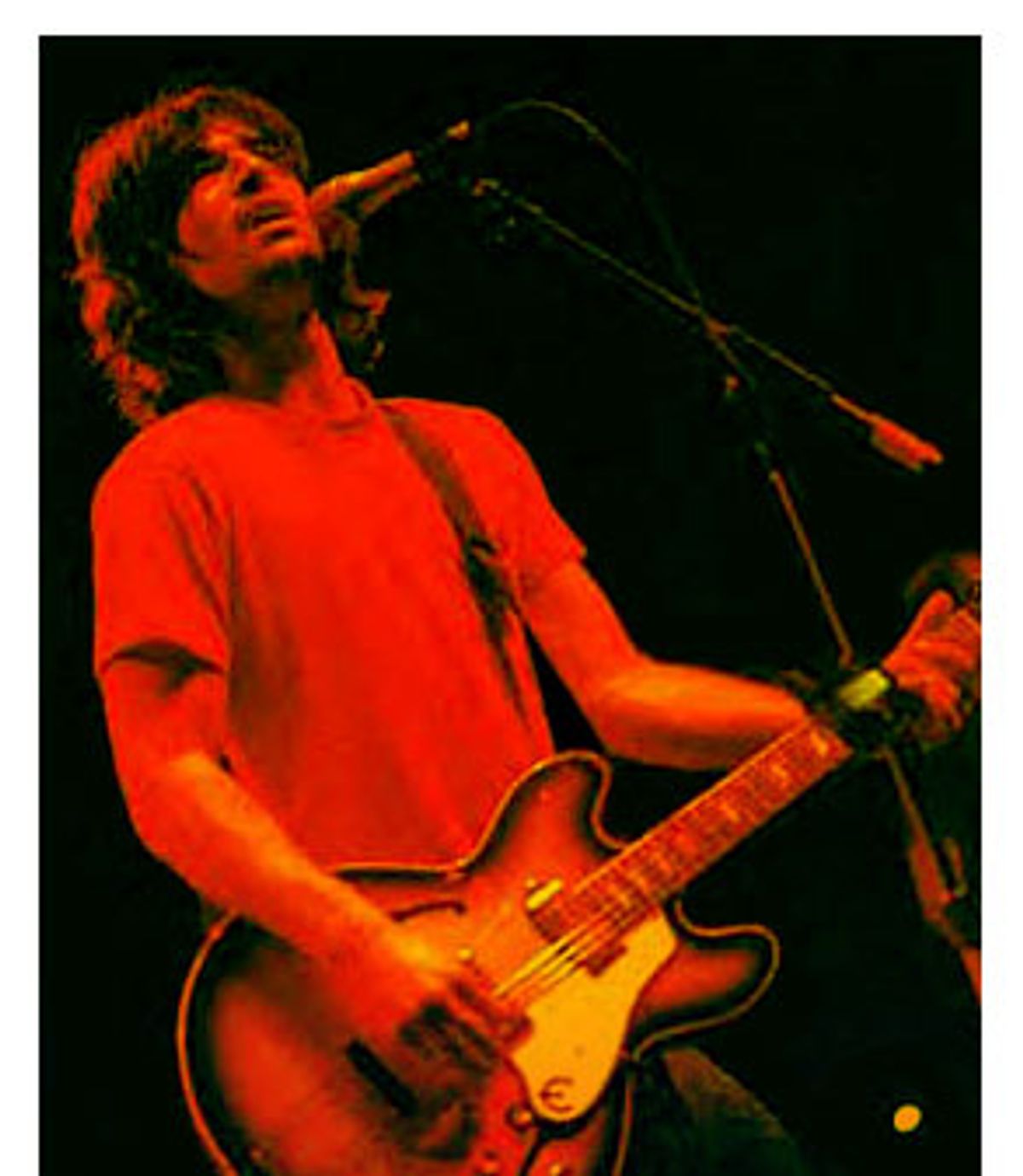

Venture to the top floor of the three-story Borders store in midtown Manhattan, and chances are the first face you'll see will belong to Pete Yorn. Squinting out from the cover of his second album -- the record has been conspicuously displayed to meet the gaze of buzz-hungry shoppers stepping off the escalator -- Yorn has the eyes of a handsome brooder and hair so thick it might flunk a test for performance-enhancing substances. He looks like a cross between an "On the Waterfront"-era Brando and a dark-maned Kurt Cobain. In other words, Yorn is this year's Rock God in Waiting.

The folks at Columbia Records are all too aware of what they've got on their hands; the label clearly envisions the 28-year-old New Jersey native as the successor to another famous Garden Stater, a fellow named Bruce Springsteen. If you doubt me, check out the packaging and liner notes of Yorn's new record, "Day I Forgot." Then have a look at Springsteen's breakout 1975 album, "Born to Run." The black-and-white photos, the soulful gaze, the common-man lyrics -- it's all there, just like it was 28 years ago.

Here's the problem: The kid doesn't have the goods. This is evident not so much in contrast to Springsteen's most-beloved record -- talk about an unfair matchup -- but in comparison to Yorn's peers, fascinating rock songwriters like Brit hellraiser Ed Harcourt, Seattle's urban folkster Damien Jurado or Phil Elvrum of the weird and wonderful indie band the Microphones.

In a way, Yorn is everything that is wrong with contemporary rock and pop. The epitome of a mediocre (but carefully packaged) soulful white boy who looks good in publicity photos, he represents something very bad and very annoying about the relationship between labels and the rock writers who make careers of regurgitating press releases.

This is not to suggest that all rock writers are dumb. (You might be excused for thinking that, though, if you look at all the ink still devoted to a band like Pearl Jam, all the praise heaped on Springsteen's simply awful "The Rising," or the fact that some critics are actually paying any attention at all to Lisa Marie Presley.) Consider, for example, the vastly different career paths of Yorn and the best songwriter of this era, Lucinda Williams.

Where Yorn came out of the box as a sort of genetically engineered slacker hunk with a catchy but ultimately unsatisfying debut (2001's "musicforthemorningafter"), Williams slogged away for nearly two decades before Middle America took notice. She was 45 when her magnificent 1998 effort, "Car Wheels on a Gravel Road," made her a star. The odd thing is, Williams would never have made even a small dent in the popular consciousness without the support of the same critics who are salivating over Yorn.

Where Yorn is a case study in how critics can wield their power to turn a middling rocker into a supernova, Williams is the opposite; she was, in large measure, a creation of journalists who saw that she was the real thing and refused to give up on her. It took her five years to finish "Car Wheels," but her fans in rock writerdom never wavered. When radio ignored the record, the Village Voice's influential "Pazz and Jop" poll revived it. By 2000, the New Yorker had deemed her worthy of a 12,000-word profile, and her name was on the lips of every knowledgeable rock and country fan.

Williams' seventh album, the thoroughly (and deservedly) praised "World Without Tears," was released this spring within a week of Yorn's. "World" isn't Williams' finest effort, but it is remarkable in its own way. "Minneapolis," for one, is as affecting and poetic as any song that will be released this year. Singing through a set of clenched teeth and sounding not unlike a hillbilly Sarah Vaughan, Williams wishes for purer thoughts, ones that resemble "the heavens and the spring's virgin buds." A moment later, she's decided that it's time to give up on an ex-lover: "You're a bad pain in my gut/ I wanna spit you out."

By contrast, ready-made superstar Yorn's weaknesses (a so-so voice and lyrics that, as you'll see in a moment, are trite to the point of comedy) become especially bothersome when one considers how little time it has taken him to win a career's worth of praise. It has been just two years since MTV2 put his debut single, "Life on a Chain," into heavy rotation, and yet Yorn has been anointed the rock 'n' roll "savior" of a new millennium. Blame the Columbia marketing team for this; the flaks at the Sony subsidiary have done such a stellar job of selling Yorn as alterna-hunk that everyone from the Boston Globe to Entertainment Weekly has mistaken him for an "indie" artist. (By this logic, Barbra Streisand, Iron Maiden and Destiny's Child, all of whom are Yorn's label mates at Columbia, are also "indie rockers.")

Yorn does deserve credit for being a pretty fair musician; in addition to his workmanlike vocal turns, he plays the guitar, bass, drums and piano on "Day I Forgot." But regardless of how many instruments he picks up, there is simply no excuse for the record's lyrical laziness -- he seems bent on setting some sort of new mark for hackneyed songwriting. At various points during the album's 14 songs, Yorn begs an ex to "come back home." Oh yes, and when you get here, just "take my hand," he pleads. He plays the sage ("You only fall in love once") and the New Agey prophet ("You don't have to walk alone"). He's a defiant romantic ("I don't love you") and a heartbroken teenager ("There was a time when I thought I knew you").

Nothing, though, will prepare the listener for the song titled "Burrito." Set against a sort of needling, faux-Ramones guitar intro and his muscular bass and drum work, Yorn spends three minutes singing a series of stanzas that he will likely spend 30 years regretting. "It's a 7-Eleven," moans our overenunciating hero. "Do you wanna take a walk outside/ If you want a burrito/ You can have another bite of mine." It's a lyrical low point on a record full of them.

Yorn's problem is one that plagues many a young rocker: He has no idea who he is. At different points on "Day I Forgot" he sounds like he's aping Brit rocker Richard Ashcroft ("Carlos [Don't Let it Go to Your Head]"); early Wilco ("Pass Me By"); an amped-up Springsteen ("Come Back Home"); and the Pixies ("Burrito").

Now if you're a young rock frontman with contrived angst to burn, there are worse things than trying to imitate Springsteen or Wilco's Jeff Tweedy. But this is a record without an identity, forged by a guy who owes his success to a great head of hair and a savvy marketing push. Yorn may someday prove me wrong; he'll never rival the greatness of someone like Springsteen or Lucinda Williams, but he may in fact have the goods. There's no sign he'll be delivering them anytime soon, though.

Shares