When I read the track list for Tori Amos' new greatest-hits collection, "Tales of a Librarian," I was almost glad to see that "Little Earthquakes," from her debut of the same name, wasn't included. It would be a solid choice, but whenever I hear it, the years collapse and I'm jerked back to 1991. It's Tuesday. The guy I think I love just told me he's skipping the country ... oh, and he's seeing somebody else. I'm lying on a hardwood floor, staring up at tear-blurred nothing. I call in sick to work. I am sick. But I'm just well enough to reach up and rewind a linty, distorting Maxell tape of "Little Earthquakes" about 40 times -- fading out into its crashing piano paroxysms, floodgate-busting changes, Kate Bush-meets-"Carrie" vocals, and histrionic observation: "Doesn't take much/ to rip us/ into pieces."

Like the protagonist in French director Marina de Van's recent film "In My Skin," Tori Amos is obsessed with her body, with the smeared line between healthy and hurt. De Van's movie, which has a poker-faced blast injecting Cronenbergian horror with French feminist theory, concerns a young female marketing exec who, once injured, begins to push the limits of her sovereignty over her own flesh. Her physical self becomes a science project, a source of raw material for craft, a source of food. Her nerve endings are just land mines lacing a rich, plunderable country. Since Amos sforzandoed onto the nascent alt-rock scene at the apex of grunge with her bench-humping cover of "Smells Like Teen Spirit," she's written about the physical effects of love and hate, about spirituality playing out on the body's battlefield. Earthquake as bad-love orgasm. Bad love as laceration. Shame as crucifixion. Menstruation, sex, rape, miscarriage, pregnancy -- as, well, as themselves.

For many girls coming of age in the '90s who weren't in conversation with the equally graphic punk rock riot-grrrl scene (and some who were), Amos' candid acknowledgments -- set to swoopingly infectious Andrew Lloyd Webber-ish melodies -- were galvanizing. "Earthquakes'" powerful "Winter" locates fearsome change in graying hair, "Silent All These Years" imagines the protagonist's body, trapped in her boyfriend's jeans, as suddenly piscene. "Precious Things" starts with a twisted ankle and ends with "Nine Inch Nails and little fascist panties tucked inside the heart of every nice girl." "Crucify" translates stigma as stigmata. And the rape novena "Me and a Gun" involves the arresting image of a bent, breaking girl, stomach down on a Cadillac Seville.

Amos' religion-flouting inquisition of the female corpus continued with 1993's "Under the Pink." The associative hopscotcher in her denial-tailspin hit "Cornflake Girl" escapes to "sleepy-time" just as "things are getting kind of gross." The bad-father fuck-off "God" alerts the big guy to the fact that "a few witches burning gets a little toasty here." The title of Amos' 1996 album "Boys for Pele" refers to a fantasy of cad-like ex-boyfriends being fed to a Hawaiian volcano goddess.

In 1997, "From the Choirgirl Hotel" offered the miscarriage lament "Spark," which found the exhausted Amos, who has spoken frankly about losing touch with her sexuality during her pregnancy struggles, "doubting if there's a woman in there somewhere." The residual moralism of the singer's Methodist upbringing pops up on that record's weirdly guilty "Playboy Mommy," an apology to an unborn child for mom's libertine choices.

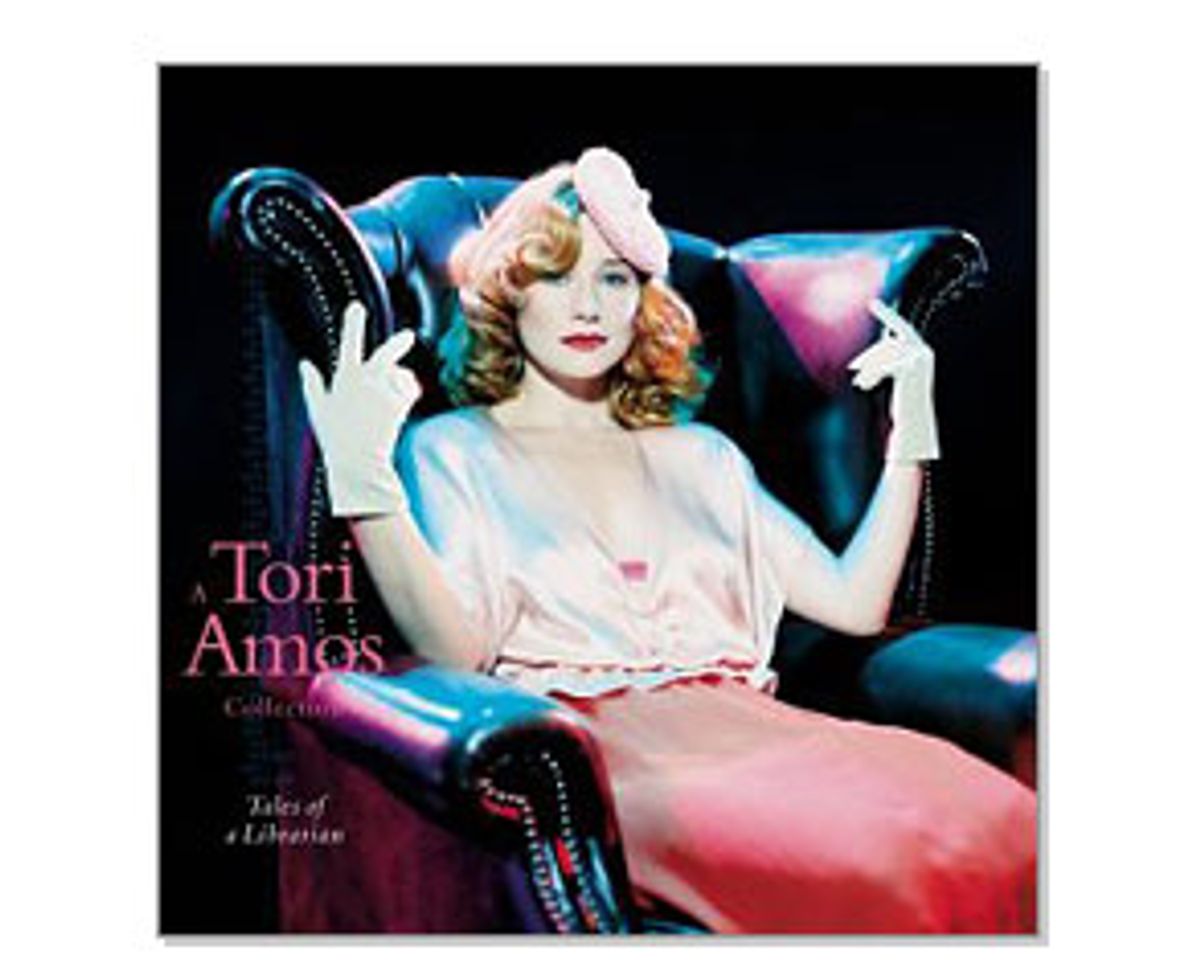

Listening to the new 20-song "Tales of a Librarian," which collects these and other fan faves from Amos' years at Atlantic Records (the bonus DVD contains only a few live soundchecks, snapshots of Amos playing dress-up, and what counts as cheesecake for the famously modest diva: a couple of still-shot bra-with-jeans flashes), it seems more like a series of audio snapshots from the collective bildungsroman of alt-girlhood than an essential listening experience for the as-yet-uninitiated. It's hard to imagine what a teenaged Avril Lavigne fan or devotee of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs' intact hipster bravado might make of Amos' body-rending catharses, her Jackie Kennedy odes, her New Age quirk.

Along with the aforementioned selections, "Tales of a Librarian" also includes "Mr. Zebra" and "Way Down" (from "Boys for Pele") as well as the Camelot script-flip "Jackie's Strength" (from "Choirgirl") along with rarities "Mary" (virgin-whore issues, martyrdom and lots of bleeding) and the George H.W. Bush-bashing "Sweet Dreams." I'm not sure if the pretty new song "Snow Cherries from France" is allegorical or just decorative diary lore, but another new ditty, "Angels," is a moment of cuckoo genius, casting Florida's hanging chads from the 2000 presidential election as struggling seraphim "trapped" by earthly evildoers.

This foray into politics continues the direction mapped in her last record -- not excerpted here, since it wasn't released by Atlantic. That album, "Scarlet's Walk" (Epic), was a moving and expansive road-trip travelogue in which Amos uncharacteristically stepped outside herself to commune with post-9/11 America, mixing essences with the likes of Navajo spiritualists and Hollywood strippers, and of course, the title's tragic Southern belle. It was a device that served Amos well, allowing her to traverse the land as an extension of traversing the body.

The expanded scope of most of "Scarlet's Walk" -- the reach beyond the self -- evidences a sociological curiosity and political bravery grown out of personal contentment. New material documenting bliss with cats, gardens, husband and child is predictably less interesting than her outward-looking observations, but it functions almost as a dispatch from a formerly crazy friend who figured out a way, albeit a bourgeois one, to survive.

It's somehow appropriate that Amos shows up in the feel-weird holiday movie "Mona Lisa Smile," the Julia Roberts vehicle that on the one hand means to plug radical feminism but also ends up validating here-and-now post-feminist backlash. Our redhead fronts Wellesley College's 1953 Spring Fling swing band, crooning torchily for girls who seek men and marriage as a shelter, or perhaps even a safe base of operation for their newly-minted Ivy-esque intellects. Amos' startling presence commands the camera's attention -- she's the idiosyncratic, brash, sometimes itch-inducing avatar of this very paradox.

Shares