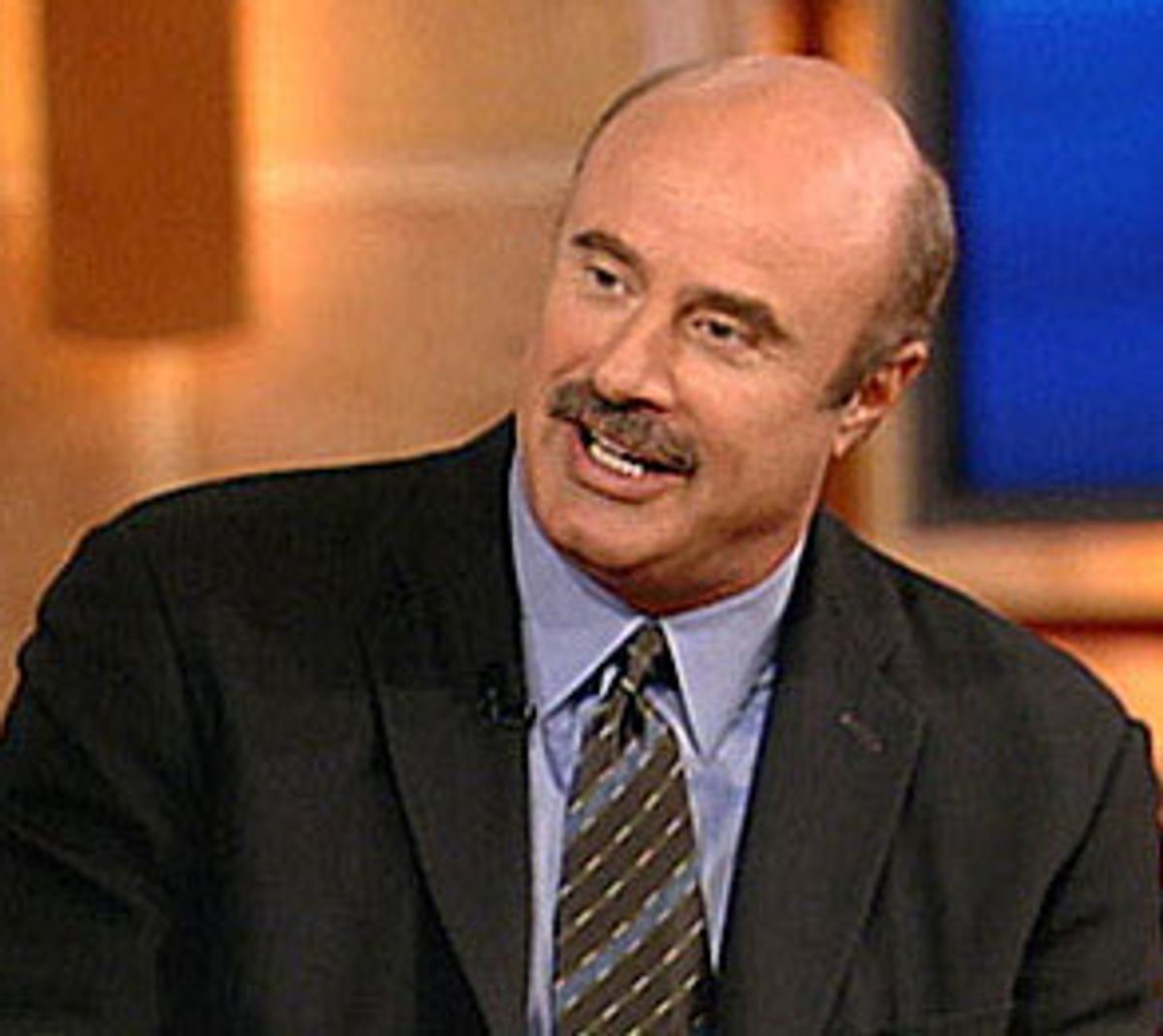

Dr. Phil, as millions of strangers affectionately call superstar Texan psychologist Phillip C. McGraw, is huge. At 6-foot-4 and 235 pounds, he can easily block your entire field of vision, even when he is slouching a little, trying to get right up in a guest's face.

I know this because I wound up sitting directly behind him at a live taping of his eponymous show last week, and I had to watch his guests on the monitors. The solid ratings of "Dr. Phil," the show, match the Frigidaire dimensions of Dr. Phil, the guy. The show earned a 4.2 household rating in the first week of November sweeps, making "Dr. Phil" the second most-watched syndicated talk show after "Oprah," and the most highly rated new one since the dawn, more than half a decade ago, of "Judge Judy."

Given Dr. Phil's popularity and the apostolic devotion of his fans, it's a little surprising that getting a seat in the live studio audience turns out to be so easy. I know from traumatic past experiences that sitting in a studio audience requires more than just sitting; I know that a team of professional audience-warmers is poised to shuck us of our dignity and put us through a rigorous program of escalating pep that will culminate in everyone getting up and dancing to "Celebration" at 9 a.m.

But my mom is visiting and she's a fan, so I decide to feel the fear and humiliate us anyway. We dial 323-461-PHIL, leave a brief message and a nice woman soon returns my call. "So, you'd like to be a part of Dr. Phil's audience," she says, in a tone similar to the one Jerry uses for his kids. "How does tomorrow sound?" It sounds terrible, but she makes me feel, for a fleeting moment, like my fondest wish has been granted.

The whole "Dr. Phil" experience, in fact, crackles with this beatific, fairy godmother vibe. The woman on the reservations line hums with it, as does the pre-warm-up video we watch while filling out our release forms. It lights up the audience wranglers and makes them twinkle like a string of cheap Christmas lights.

Every show that is taped in front of an audience features professionals in charge of manufacturing energy, and "Dr. Phil" is no exception. After an audience warm-up that includes a twisting contest, a run-through spontaneous standing ovation, and a silly audience contest ("You turn on the TV and the enthusiasm seems so natural," my mom says as we simulate clapping wildly, "but, my God, it's a wonder they don't stick a hot pepper up your ass"), Dr. Phil finally struts out on stage and announces that Oprah is due to drop in any minute. Psych! There's something emotionally complicated about the whole thing. (The subject of the day's show is "Self-Defeating Strategies," which seems somehow appropriate.)

But the evangelical feel is real, too. Dr. Phil is a therapist so blunt, decisive and close (enough) to the land (he's from Texas, after all) that he might as well just club the conflicted souls who appear on his show with a magic wand and drag them back to the "life strategies" cave. He imparts his nuggets of wisdom as though he were laying on hands. His audience has flocked to him, that is, at least as much as an audience that has called a reservation line and lined up at a Paramount Studios side entrance can "flock."

Dr. Phil specializes in "wake-up calls" that help people "get real" and change their lives. Apparently, there's no snooze option. Judging from the unqualified success stories featured in the 75th "Dr. Phil," which aired last week, his approach never fails. The show asked previous guests to return to the show, after having had the sense beat into them, and report on their progress.

Here's how they did: The mother of the weird Boy Scout family is forever indebted to Dr. Phil for showing her husband the error of his ways. Before Phil, her husband didn't understand that Mother's Day and wedding anniversaries were not optimal days for spending time with the troops. After Phil, he will now occasionally swap his Boy Scout uniform for some tights and puffy sleeves, in order to spend an afternoon with the family at the Renaissance Faire. Before Phil: A man refuses to sleep with his wife, preferring to cuddle. After Phil: He learns that sex is an important part of a relationship after all. Thanks, Dr. Phil!

Sitting in the audience, listening to people offer up their problems for Dr. Phil as a supporting audience clucks and coos its approval feels oddly ritualistic. If you have ever wondered what makes people get up on national TV to talk about their problems, attending a taping makes it a little easier to understand.

Close-ups of talk-show guests on TV tend to create the opposite effect they purport to be after, often making the people seem more alien than they did already. The set of "Dr. Phil," however, creates a weirdly intimate space, a sort of public confessional. Dr. Phil listens to the problem, lets fly a few zingers caustic enough to peel paint, produces some kind of magical celebrity gift -- acting advice from Ted Danson to an aspiring actress, a year's free psychotherapy to a woman who rages against her child -- and sends his charges on their way. This is Dr. Phil's M.O.: Impart, bestow, a pat on the ass and see you later. No wonder people like him.

There is another, ultimate, fairy godmother in the story, of course, and that is Oprah Winfrey. Dr. Phil was a psychologist from Dallas who traded his therapeutic practice with its "unclear" results for a more lucrative and less frustrating career as a trial-preparation consultant in civil cases. He hit the self-help jackpot when he found himself in the enviable position of lending Winfrey a hand in her time of need -- specifically, in 1998, when members of the Texas beef industry countered an offhand mad-cow quip made by the daytime talk queen with a $10 million lawsuit. After a six-week trial, Oprah prevailed.

Dr. Phil has made a lot out of the ways in which he helped his new, incredibly powerful friend refuse to settle out of court and fight for her God-given right to swear off burgers on national television, and he has dabbled in portraits of Oprah as a fair damsel in distress. An appearance on her show led to regular, weekly appearances that stretched out over four years, his three books landed on the New York Times bestseller list and, in September, he got what punier gurus only dream about -- his very own Oprah-produced show.

"Dr. Phil" debuted in 97 percent of U.S. television markets and generally airs directly before or after, but never against, Oprah's show. (And she does indeed make occasional impromptu visits.) But lumbering force of nature and nurture that is Dr. Phil notwithstanding, this probably won't ever really fly. Oprah looms large over "Dr. Phil," and you can sense that this is at least a little discomfiting to the not-so-gentle giant.

Even when she doesn't drop in, the Oprah imprimatur is all over the place. In fact, to watch "Dr. Phil" from the studio audience is to feel a little like you are watching a sequel to Cinderella in which the F.G. keeps unwittingly upstaging her protégé. You get the feeling that this is not so much Oprah's doing as it is Dr. Phil's own. Dr. Phil, the product, is still young enough to feel the anxiety of separation and the debt of gratitude; and old enough to want to be thought his own, self-made (like Tori Spelling in the early '90s) media healer and daytime personality.

Shares