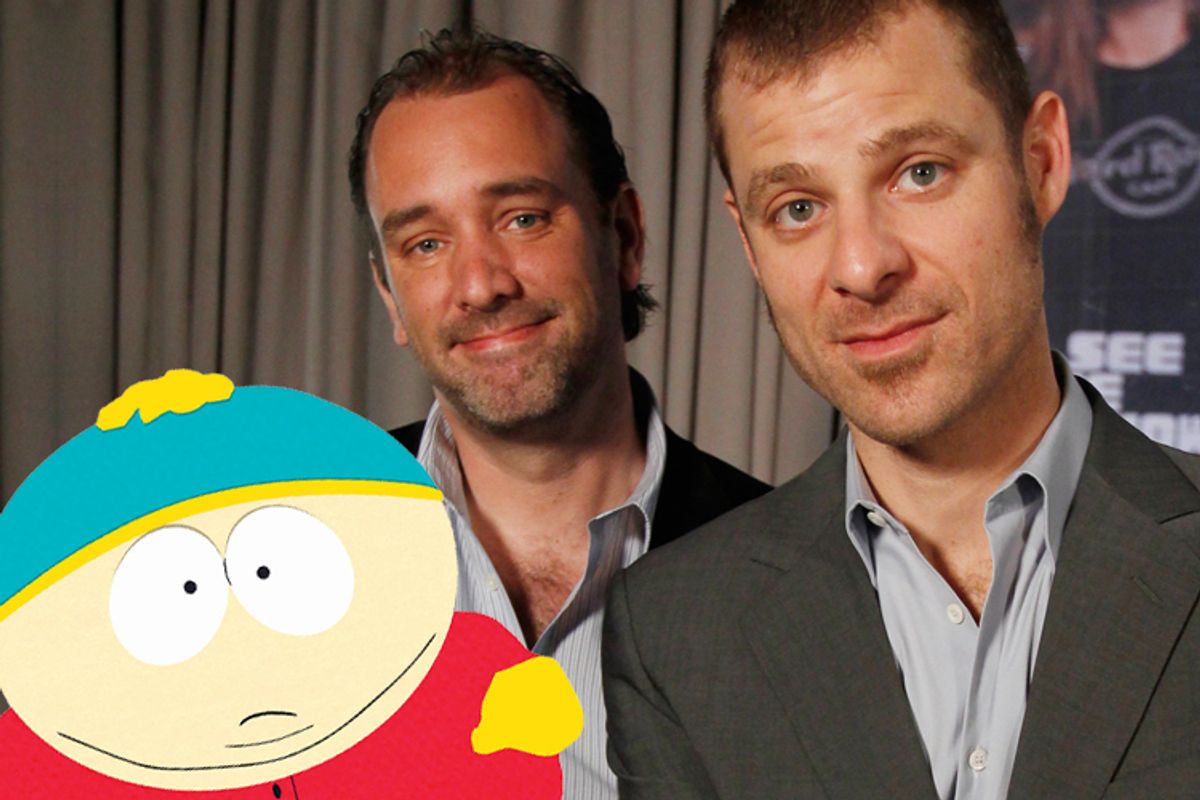

As I watched Trey Parker and Matt Stone, the creators of Comedy Central's "South Park," collect armloads of Tony awards for their satirical musical "The Book of Mormon" Sunday night, a disquieting and thrilling realization popped into my head: These potty-mouthed clowns might very well be America's greatest and most consistently inventive humorists.

Of course they have competition. There's "The Daily Show," for sure, though I'd argue that Jon Stewart's version is as much a news program as a comedy series. But for audacity, visual flair, musical chops, verbal invention and gut-busting silliness, not to mention consistency of vision over time, I think the "South Park" boys trump all comers -- including the creators of "The Simpsons," a landmark show that started to flag halfway into its endless run, and Seth MacFarlane of "Family Guy," whose show has its moments but has never quite risen to the heights of conceptually driven insanity that Parker and Stone reach so often. At their best, I'd put Parker and Stone up there with "Monty Python's Flying Circus," "SCTV," Ernie Kovacs, the Marx Brothers, George Carlin and W.C. Fields, all of whom skated along the edge of the surreal and willfully outrageous, doing pirouettes and blowing raspberries at anyone who tried, like yours truly, to call them great and significant.

Their success is all the more remarkable when you consider what true outsiders they were, and to some extent still are. Back in 1992 they were just a couple of students at the University of Colorado who'd produced a goofy little short film titled "The Spirit of Christmas." Within five years -- thanks to help from Fox executive Brian Graden, who gave them $2,000 to turn the short into a "video Christmas card" that he could send to friends and birthed the very first viral video sensation -- they'd landed a Comedy Central show, "South Park."

Their rise was so sudden that there was no reason to think they'd last. Most overnight successes freeze up in the spotlight or reveal themselves as one-trick wonders. Not Parker and Stone. They're safely ensconced in mainstream culture -- almost everything they do is connected to Viacom, the gigantic parent company of "South Park" network Comedy Central -- yet they still seem mysteriously and delightfully outside of it. What other American humorists have been so successful within the mainstream over such a long period while routinely landing on news pages (most recently for Comedy Central's censoring of their jokes about Mohammed) and maintaining an almost punk rock edge?

Sure, some episodes have been sharper and more coherent than others; like a lot of the aforementioned iconic clowns, Parker and Stone practice a type of humor that is by nature hit-and-miss. But over the past few days, I've rummaged through prior seasons of "South Park" looking for duds and have found surprisingly few. The stuff that seemed astonishingly vital at the time still does, and the stuff that felt subpar -- such as the Season 1 episode with the Ethiopian -- has proved better than I remembered, sometimes much better. Even a weak episode is likely to contain a scene or subplot so terrifically unhinged that it makes you dizzy. A "C" effort from these guys is better than a latter-day "A+" effort from "Family Guy" or "The Simpsons."

And an A+ -- such as Season 10's "Hell on Earth 2006," wherein Satan decides to rent out the W Hotel in downtown South Park and throw himself a Sweet 16 party -- is one for the ages. The Satan stuff (a continuation of the great hell sequences in their 1999 animated feature "Bigger, Longer and Uncut") is a barbed skewering of skeezy reality show participants' narcissism, and the audience's rubbernecking smugness; that by itself might have been enough to sustain a half-hour episode. But Parker and Stone aren't content to do just enough. They always want to give us more than we expected, to go further, to overwhelm with sheer imaginative excess. So they add a subplot with the boys summoning the spirit of murdered rapper Biggie Smalls by repeating his name into a mirror à la "Candyman," and yet another subplot that finds mass murderers Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer and John Wayne Gacy being dispatched from the underworld to pick up a giant cake shaped like a Ferrari and deliver it to Satan's bash. The "Three Murderers" become the supernatural version of the Three Stooges, squabbling among themselves, getting into wacky high jinks, and beating, stabbing and disemboweling themselves and various innocent bystanders. These bits are breathtaking for all sorts of reasons, one of which is that they explore the connection between comedy and cruelty incisively, but without becoming dry or self-regarding.

Another of Parker and Stone's admirable qualities is their resistance to political pigeonholing. At some point, representatives of every American party or movement have tried to claim them as standard-bearers, only to get a thumb in the eye soon after. Are the "South Park" guys liberal? Conservative? Republican? Democrat? Libertarian? Pro-choice? Pro-life? Pro-capitalism? Pro-socialism? I suspect they're mainly anti-complacency, and anti-bullshit.

I'll never forget watching their 2004 political satire/puppet epic "Team America: World Police" with two different theatrical audiences -- one in lower Manhattan, the other in suburban Dallas -- and hearing both crowds chortle as Parker and Stone beat up on people or ideals they thought worthless, then squirm when the humorists started butchering their sacred cows.

Parker and Stone fire on targets and settle scores. But their work almost always has a structural integrity that makes it feel more substantial than a rant-of-the-week. For instance, the epic, three-part, 2007 "South Park" episode "Imaginationland" is one of the definitive statements on American pop culture in the age of terrorism and endless foreign war. But it's not just a finger-wagging editorial about how to behave or not behave, or how to think about the relationship between the American imagination and the media that feeds it. It's self-contained and self-supporting, a stand-alone piece that has internal logic as rigorous as that of any big budget fantasy film that takes itself seriously.

Parker and Stone have done some of their sharpest and craziest work in the last couple of seasons -- for the record, that's seasons 14 and 15, at which point most TV series are either long-canceled or coasting on the memory of past triumphs. This season's send-up of the royal wedding -- a 12-tiered wedding cake of riffing -- was one of the single greatest episodes the show has produced. The goof on the ceremony itself (substituting the "Canadian royal family" for the Brits, with Parker-as-cable-newscaster ending every other observation with a variation of the phrase, "as is tradition") belongs on a short list of great self-contained surreal set pieces, alongside the "Hail, Freedonia" number from the Marx Brothers' "Duck Soup" and the duel with the Black Knight in "Monty Python and the Holy Grail." (You can watch it below at the 1:30 mark.) "People in attendance now gently tossing Captain Crunch as the prince passes by, as is tradition ... [The] Canadian prince now dipping his arms into the pudding, as is tradition ... The princess will, of course, scrape the pudding off the prince's arms, symbolizing their union ... This is a glorious day for our country, and indeed the world."

Last week's half-season finale, "You're Getting Old" -- in which Stan's 10th birthday afflicts him with cynicism, and prompts arguments between his parents about how one's taste in pop culture almost inevitably hardens over time -- might have made a great series closer if Parker and Stone had decided to hang it up now. But why would they when they're producing work like this, which makes an unpretentious but true statement on generational tension, aging and nostalgia without turning self-important?

Parker and Stone have managed to seem as though they're still a couple of wiseacres sitting in the back row of the classroom, goofing off and making trouble, when in fact they've spent the past decade-and-a-half winning Tonys and Emmy and Oscar nominations, and diligently assembling a body of work that should be the envy of any animator, stand-up comic or editorial cartoonist. It's been a remarkable run. And as long as the show stays interesting -- and it has; much more so than any of its long-running animated competitors -- there's no reason it shouldn't continue.

Since I've managed to go a whole column without running a clip from "Bigger, Longer and Uncut," let's close with one, shall we? All hail Satan. He can dream, too.

Shares