The question of the hour:

Which network can put the worst reality TV show on the air?

After the marvelous feint of "Survivor," which was fun to watch, CBS is the reigning champion, having, with "Big Brother," devoted more broadcast hours per week to utter tedium than anything this side of the Lawn Channel.

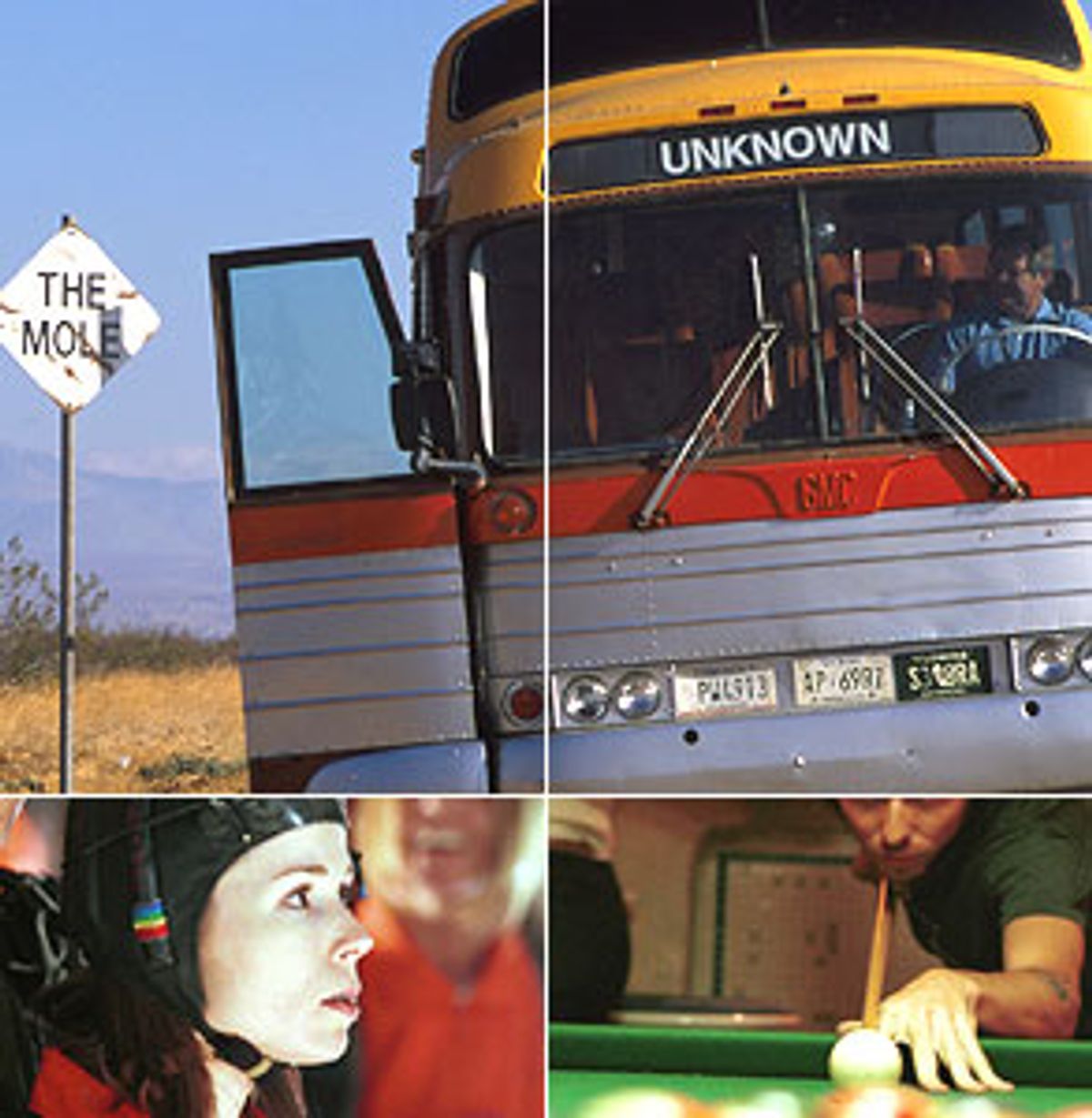

Now ABC is making its best play for the crown with "The Mole." The show debuted Tuesday with a mystifying, incomprehensible episode. From what we could discern from the rush of events, the premise is this:

A group of 10 people is put together in the Mojave Desert. They come together in various ways -- a limo, a sports car, etc. One even walks in through the desert!

This is an immediate bad sign. If the producers are staging shots from the start, how can you trust the "reality" of the show?

We meet the contestants, all of whom immediately start engaging in all sorts of "Big Brother"-style forced jollity. None of them look very interesting, though they all have easily limnable "identities."

There's Jim, former lawyer, now helicopter pilot; Afi, who wants to go to medical school; Steven, undercover cop; Charlie, retired police investigator; Wendi, display artist; Manuel, 40ish single dad from the projects; Kate, grandma; Kathryn, law school lecturer; Jennifer, corporate communications manager (shades of Richard Hatch!); Henry, bartender and "people person."

There's a host, too: Anderson Cooper. As we contemplated his noble mien, we thought about the extra-big boots he had to fill. We reflected on the profession of reality-TV-show host, whose vaunted integrity and sober self-sacrifice were established by the likes of "Survivor's" Jeff Probst and "Big Brother's" Julie Chen.

We realized we haven't thought of Chen, the pantsuited imp, in months!

On first glance, Cooper seems a very, very poor man's Probst. With his thin visage and "Matrix"-lite ensemble of black turtleneck and spiffy leather jacket, Coop looks like an extra from "Queer as Folk." He has the aggressive screen presence of a small potted plant.

Even Coop seems mystified by the goings-on. The group is picked up by helicopters, taken to an airport, put on a plane and then forced to parachute out of it! Then, over a two- or three-day period, they travel to Paris, then go by train and car to the Riviera.

Along the way, they play the game, generally little challenges or activities that the group has to perform or accomplish and for which they're rewarded money in $75,000 and $50,000 chunks. One of the 10 is "the mole," who's operating in cahoots with the producers. It's his or her job subtly to undermine the game and cost the rest of the group their money.

Here comes the complicated part. At the end of each show, the contestants are quizzed -- over a computer -- about the mole's identity. (Is the mole male or female, etc.) The contestant with the fewest correct answers is voted off the island.

Wait, that's "Survivor" lingo. Here, the victim is "executed."

The last contestant standing with the mole gets to keep the money in the pot. The elimination process is designed to both A) keep the real mole in the game and B) encourage the other participants to act suspiciously. If you act squirrelly the others will suspect you, get their answers wrong and end up banished.

Wait, that's "Big Brother" lingo.

Anyway, "The Mole" begins fast and furious. The group will get $75,000 if they all participate in the skydiving. A couple of contestants hold back -- Manuel, the goofy dad, is one of them -- but eventually all do it. (Manuel, "Big Brother" fans will recognize, is the resident George.) Then they go to France and are offered the opportunity to spend time out on the town.

The catch: If they come in late they lose $10,000. Oooh -- will someone accidentally get them lost? Then there's some folderol involving repacking one another's bags.

This last challenge creates some raw reality TV drama when it's discovered one person had only one sneaker repacked into her bag!

The most complicated game is in the South of France. We kind of object to even have to take the time to explain it, but we will: The group spends 15 minutes memorizing a lot of pointless information about one another; then two are selected to go into a side room and work out some equations using a blizzard of birth dates and such. The resulting number is then to be used as a PIN for an ATM somewhere in the small French town they're in.

This sequence includes lots of shots of the group thinking. You can see ABC is already aiming at some of the dizzying heights of televised mayhem achieved by CBS in the "Big Brother" era.

It strains credulity that people could memorize seven or eight numbers for 10 different people in a way that could allow them to come up with the right solution -- but they do.

"The Mole" is big on this information. It's put to use as well in the quiz that results in the execution each week. The contestants can't just name whom they do or do not suspect -- they have to designate who they think the mole is via questions about his or her particulars.

Over dinner, Coop soberly toasts the victim-to-be with Julie Chen-like eloquence:

"And, uh, we will miss you, whoever it is."

Well said, Coop!

In the end, poor Manuel gets it. "The Mole," like its reality TV predecessors, sure mirrors reality in one key way: Old people and minorities are quickly lined up for disposal.

A couple of the women cry. "He had a pure heart," sobs one. We get a quick "Manuel, we hardly knew ye" collage, complete with heart-tugging slow-mo. "You played a great game," mumbles Coop. Uh, actually, he didn't -- he was bounced about 44 minutes of airtime after we met him!

We're going to go out on a limb and suggest "The Mole" is no "Survivor."

It's a lot more like "Big Brother." For one thing, you just don't trust the setups. At the end of the show, there's a legend that says the show altered the sequence of the airplane jump. This is one of those disclosures that just raise more questions. The point of the jump is that a couple of the contestants -- Manuel and Steven, the undercover cop -- hold back. (The challenge, remember, was that if all of the group doesn't jump it forfeits the money, and it's the mole's job to cost the group its money.)

Was it really not Manuel and Steven who jumped last? If it was one of the first eight, why would the producers even bother to change the sequence?

If "The Mole" is based on the analysis of information, the producers need to be more careful with it.

But the biggest problem is the voting method. It's not entirely clear, but apparently the contestants vote by means of what they remember from the big memorization session. This seems far too haphazard.

But in the end, we understand why Manuel got bounced: Everyone knows that the 2001 model of Chicken George could not possibly have the chops to be the mole.

Bill Wyman

Shares