From the "The Brady Bunch" to "Home Improvement," from Ralph Kramden to Ray Romano, the middle class has always had a comfortable spot on our TV screens, and Americans always seemed to prefer it that way. Remember in the late 1980s, when the couples on "thirtysomething" were considered self-absorbed whiners with too much time and money on their hands? People seemed rattled by these families who were, with their two incomes and conspicuous consumption, relatively more affluent than the viewers at home. What happened to jeering those greedy bastards on "Dallas" -- or at least giving the raspberry to "The Beverly Hillbillies'" pompous banker, Mr. Drysdale?

Well, hold onto the arms of those threadbare La-Z-Boys, because this fall's lineup makes the Steadmans of "thirtysomething" look absolutely destitute by comparison. The filthy rich aren't caricatures anymore, and the default for TV characters is no longer middle-class like it was 20 years ago. Gone are the battered couches of "All in the Family," the teenagers with summer jobs of "Eight Is Enough," and the grumbling and penny-pinching of Mr. C on "Happy Days." Even the upwardly mobile jubilation of George Jefferson seems positively provincial, in light of the flawlessly designed lofts and finely appointed multimillion-dollar homes inhabited by your average TV character today.

Today's TV denizens aren't just comfortable, they're loaded. Even as the mortgage crisis exposes the fragile foundation that lies beneath our culture of excess, the TV industry trips happily along with its tales of stylish executives attending gala functions in couture gowns. Whether it's the glamorous businesswomen of ABC's "Cashmere Mafia," quipping about their big-deal jobs over an expensive lunch, the rich men of ABC's "Big Shots" having drinks on the veranda at their exclusive club, or the sugar moguls of CBS' "Cane" wheeling and dealing in their antique-lined smoking rooms, the backdrop is always big money. Even if we're shown that the Hilton-inspired troublemakers of ABC's "Dirty Sexy Money" or the angry, backstabbing prep-school brats of CW's "Gossip Girl" are deeply unhappy, desperate people because of their wealth, it still only feels like an excuse to show them unraveling over drinks at the Palace Hotel, or wandering listlessly among the clothing racks at Bergdorf's. While the tag line for NBC's midseason "Lipstick Jungle" -- "These women aren't looking for Mr. Big, they are Mr. Big" -- should feel empowering, the notion that the almighty dollar is the only surefire escape from the desperation of the late-30s single is more than a little noxious. Even on the new dramas that aren't focused on money or power, like HBO's "Tell Me You Love Me" or Showtime's "Californication," characters live in massive, pristine houses, eat at expensive restaurants and wear flawless designer clothes. While the gap between rich and poor in this country widens to an almost inconceivable chasm, our TV sets conjure a vivid picture of an American dream that most of us can't begin to attain.

Naturally the entertainment industry has always glorified what economist Thorstein Veblen referred to as "conspicuous leisure" -- consumption used to signal status. But in the old days, shows about the ultra-rich and powerful served the perceptions and prejudices of the common man. On "Dynasty," Krystal represented a down-to-earth woman unspoiled by wealth, an unfrozen caveman to Blake Carrington's addled capitalist, and her sworn enemy was Alexis, a power-grubbing, money-hungry demon forged in the hellfires of pecuniary excess. Similar class distinctions played out on "Dallas," "Falcon Crest" and even "Little House on the Prairie." Whether the spoiled, shortsighted rich girl was Lucy or Nellie, the message was the same: Very rich people aren't just deeply tacky, they're morally corrupt.

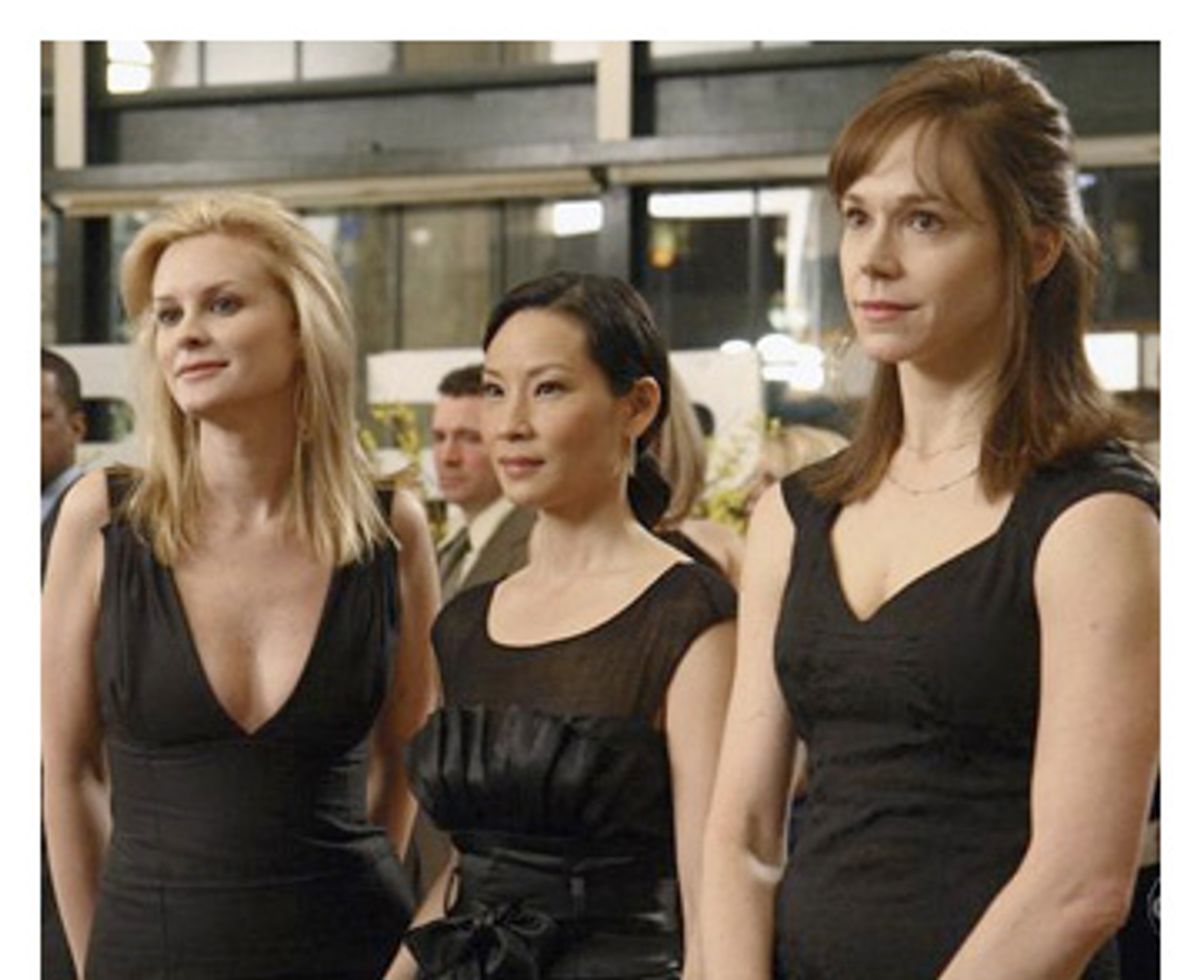

As inaccurate and cartoonish as that picture may have been, the alternative presented by today's dramas is insidiously benign. On ABC's "Cashmere Mafia," we're clearly meant to admire and respect the four female MBAs, who traipse happily from boardroom to pricey luncheon to posh benefit function, expressing their deep gratitude for each other in mostly monetary and status-centered terms:

| Emotional Statement | "Cashmere Mafia" Translation |

|---|---|

| "I fell in love at first sight!" | "I wanted to book a week in Paris right then and there!" |

| "I'm your true-blue friend." | "I can get you a great table at the Waverly Inn." |

| "I think I'm ready for a commitment." | "I found the perfect place. East 60s, huge master, three fireplaces," |

| "I want to keep my marriage together." | "I love having someone to come home to, to go to parties and do the postmortems with." |

| "I really need your support right now." | "Now I know you all bought tables for the benefit Thursday, but I would really, really appreciate it if you were all actually there." |

| "Let's change the subject." | "I loooove that dress!" |

| "Cheers!" | "Here's to friends in high places!" |

While most of this fall's new soaps unabashedly celebrate wealth and offer up vicarious thrills of conspicuous consumption at every turn, the shows that hedge their bets with self-consciousness and the thinnest gloss of self-righteous rhetoric are even more grating. "Money makes everything go wrong," intones Nick George (Peter Krause) at the start of "Dirty Sexy Money," and at least he has our attention. "That's certainly what I always thought." After a whirlwind tour of Nick's sad childhood, during which we learn that his lawyer father neglected his own family to attend to the needs of the very wealthy Darling family, and his mother ended her own life over it, we find Nick in Tripp Darling's (Donald Sutherland) office, accepting his father's old job. Oh, but he'll be making $10 million, which he plans to give to the orphans, of course! Let's not strain too hard, folks. We understand how important it is for you to believe, from your spacious office on the studio lot, that every man and woman alive will sell his or her soul for a price.

Oh, but the Darlings are so deeply unhappy, those poor little spoiled brats. "I have the worst life in the world!" playboy son Jeremy (Seth Gabel) whines from his perch in the family limo. "Jeremy, shut up," Nick responds. "You have all the money you're ever gonna need. You're never going to have to work a day in your life. Thirty thousand people die of starvation every day!"

"You don't understand," says Jeremy, and exits the limo in a huff. He has a point, of course. As Chuck (Ed Westwick), the poor little rich misanthrope from "Gossip Girl" puts it to his (also rich) friend, "What we're entitled to is a trust fund, maybe a house in the Hamptons, a prescription drug problem, but happiness doesn't seem to be on the menu." To be fair, both "Dirty Sexy Money" and "Gossip Girl" take pains to demonstrate the self-pitying traps and the excesses of the ultra-wealthy. While the loaded parents on "Gossip Girl" prove to be hopelessly selfish and self-involved and the Darlings try to buy their children happiness, only to end up driving most of them to the extreme opposite, the moral of these two stories would have a little more weight if they weren't surrounded by the dazzling flash of light bulbs and the buzz of fascinated bystanders. We're reminded, at every turn, that money doesn't solve anything, yet not only are we interested in these people primarily because they're rich, but we're also shown how Nick, their high-priced on-call lawyer, gets them out of one bind after another -- the sorts of binds that would have the regular folk among us doing hard time. And that's not to mention the endless fascination with the trappings of wealth that linger in every scene. "Jeremy, can't you put on something nice?" Letitia Darling (Jill Clayburgh) asks her son, to which he replies, "Mom, this shirt cost a thousand bucks." Oh, tee hee! She didn't realize how nice it was!

So where is the middle class in this equation? In the old days, we'd find them on sitcoms, at the very least. Yet these days, even sitcom characters live sophisticated urban lives in roomy, tastefully furnished apartments or massive homes. "Friends" paved the way with those poor, struggling twentysomethings with their designer clothes and cavernous apartments, and ever since then characters have been moving on up -- and up and up -- from the impeccable taste of "Will & Grace" to the yachts and mansions of "Arrested Development" to the private schools, expensive cars and big houses of "Weeds," "Californication," "Notes From the Underbelly," "The New Adventures of Old Christine," "Entourage" and more. Other than "Friday Night Lights," "The Office" and a handful of cop shows, America's middle class is tough to find. And if you go looking for the working class, be prepared to find mostly criminals and ex-criminals, as on "My Name Is Earl" and "Prison Break."

You will find regular, everyday people on reality shows and game shows and design shows, of course, jumping up and down and screeching over the thought of winning $10 million on "The Power of 10," toying with each other's sanity for half a million on "Big Brother 8," or being redesigned and reinvented on "Extreme Makeover," where we're taught that the next best thing to being really rich is passing for it. Average people are our playthings, beneath our respect, manipulated into demonstrating their weaknesses so we can feel stronger as we miss payments on our mortgages and long for a lifestyle that magazines and newspapers and TV shows tell us everyone else out there is enjoying, except for us. Ultimately, normal middle-class people only interest us inasmuch as we can change them into something else, something far more interesting ... like minor celebrities, or rich people!

All of which is pretty funny -- when it's not making us sick to our stomachs, that is. As the economy skids, pundits scoff at the excesses of Americans who take out huge mortgages for five-bedroom McMansions, finance their Lexuses with adjustable-rate home equity loans and charge flat screens on their credit cards. But no one seems to consider it remotely odd that entertainment and media industries continue to celebrate an upper-crust existence that only a small percentage of the population will ever attain. It's not hard to see where Americans got the idea that a normal-size home and regular clothes will never be enough. Twenty or 30 years ago, after all, TV characters had cheap clothes and tacky furniture and bad hair, and they were happy to be getting by. Shows like "Roseanne" and "Laverne & Shirley," and more recently, "Seinfeld" and "Everybody Loves Raymond," brought us regular families with regular jobs and regular problems. Remember when people on TV talked all the time about whether or not they could afford stuff? These days, such conversations would be seen as deeply tacky if not utterly declassé. Aside from the teary-eyed families on "Extreme Makeover: Home Edition," whom we're told will be magically rendered happy by some combination of a redesigned family room and a brand new pickup truck, normal folks and their struggles aren't just uninteresting, they're somehow tainted. Unless there's a new wardrobe, a redone kitchen and a big check around the corner to save them from mediocrity, we don't want to know about it.

It's been obvious for years that Veblen's standard of pecuniary decency -- the minimum amount of conspicuous consumption one must maintain to be considered acceptable -- keeps inching higher and higher in this country, until Americans consider themselves struggling unless they're taking luxury spa vacations or redecorating that unbearably tacky half-bath. These notions aren't formed out of thin air, though. As a scan across the dial this fall makes clear, the TV doesn't just celebrate the supreme excitement and importance of money, it presents a lavish lifestyle as the norm, while casting average Americans as its money-grubbing guinea pigs, poised to stab each other in the back in the pursuit of the material wealth it taught them to covet in the first place.

In an interview with Three Monkeys Online about his book "Status Anxiety," Alain de Botton explains that just as in the Middle Ages, when people were surrounded by images of religious piety, we're influenced dramatically by the images we see on TV. "[I]f we are surrounded by images of beautiful rich people, we will start to think that to be beautiful and rich is very important." By skewing our perceptions of what's normal and romanticizing lives that are anything but, the excesses on our TV sets lead us to embrace expectations of happiness and success that we will likely never achieve.

"The love of money is the root of all evil," Nick reminds us at the start of "Dirty Sexy Money." "That's what they say, anyway." But we're meant to take this weakest of straw men and knock him over in one blow. After all, if loving money is evil, who would ever want to be good? In the world of "Dirty Sexy Money" and so many other shows, being good means being safe and unsexy and utterly boring. Being good is tantamount to being powerless, a nobody, the kind of person who fetches coffee for the women on "Cashmere Mafia" or the men on "Big Shots," the kind of person who loses on "Big Brother."

And so our outsize desires run roughshod over our happiness, while the TV screen leads us to believe that we're all alone in our cramped apartments with our bad shoes. Hopelessly outdated, wretchedly underpaid, and all alone.

* * * *

For more Salon TV Week coverage, click here.

Shares