The days of the great American newspaper drama appear to be gone for good. Perhaps it's the public's ambivalence about the media, so easy to malign for giving us the dirt we hate ourselves for loving. The noble, crusading reporters of "All the President's Men" seem more than a generation away from us in terms of naiveté. (Today they'd just be accused of promoting a liberal agenda.) Besides, by now most people realize that the best journos don't really prioritize "saving the children" or "making a difference" or whatever platitude we intone when genuflecting to the conventional virtues of the day. Real journalists just want to get at the truth, and the truth can be a very nasty thing indeed.

The newspaper reporters at the center of Paul Abbott's tense, serpentine thriller, "State of Play" -- originally broadcast as a six-part miniseries on BBC in 2003, and now out on DVD -- are not especially nice people. They're crafty and pushy, full of sneaky tricks like setting off a car alarm to flush out a source, or pretending to be a bike messenger to snag a handwriting sample. They lie to and flirt with and browbeat their sources, and when that fails to get results (which is often) they do something likely to shock their top-drawer American counterparts: hand over fat envelopes of cash. (Equally transgressive on this side of the pond is their propensity for secretly tape-recording just about every conversation they have.)

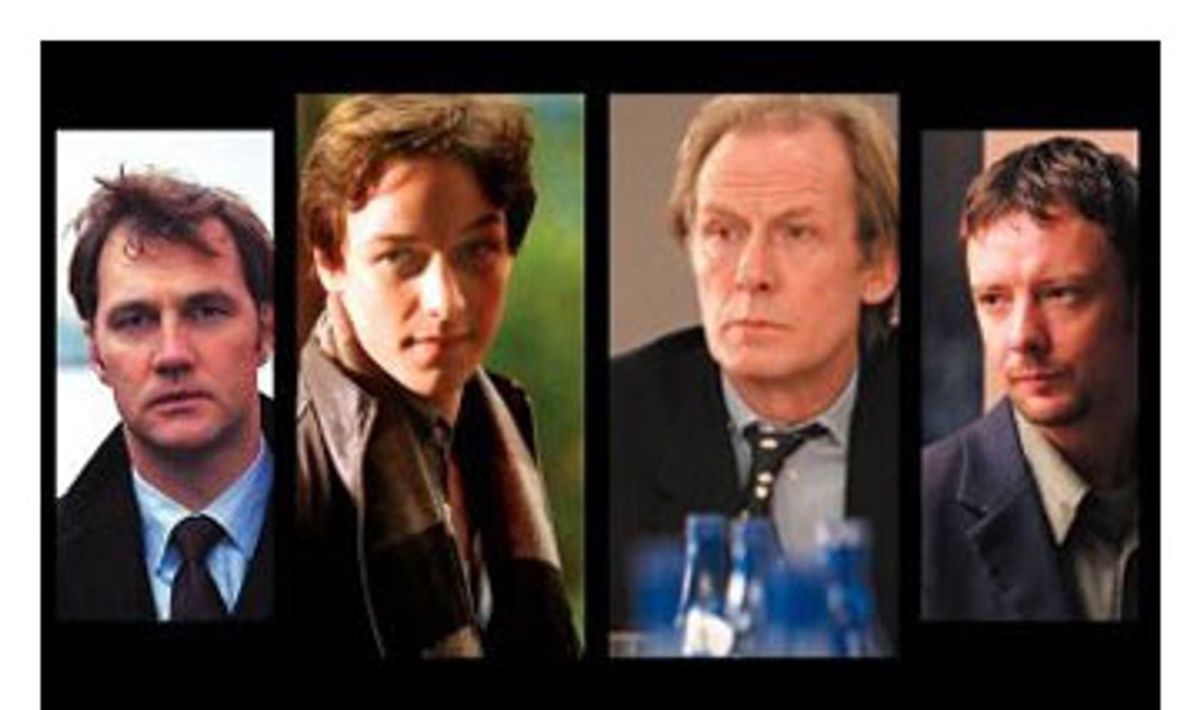

Still, they root out the truth, and when they're hot on its trail, they get a certain wild light in their eyes that's unmistakable. It's the hot gleam of reportorial lust, an essential passion in any good journalist and an undersung but crucial resource in any free society. These reporters are played by some of the best British actors around, not just James McAvoy, in a supporting role ideally suited to his clammy schoolboy prettiness, but also a sublimely dissolute-looking Bill Nighy as the editor in chief of the Recorder, the series' fictional broadsheet, the luminous Kelly Macdonald and, finally, John Simm ("Life on Mars"), all nervy, resentful intelligence as the story's hero, Cal MacAffrey.

The story begins with two deaths in London: One is the seemingly drug-related shooting of a teenage boy and the other the apparent suicide of a young woman who worked as a researcher for up-and-coming Labor M.P. Stephen Collins (David Morrissey). Stephen breaks down during the otherwise routine news conference announcing Sonia Baker's death, and the tabloids are all over him. He confesses to having had an adulterous affair with her, and turns to Cal, who was his campaign manager nine years earlier, seeking a more sympathetic outlet in the press.

Cal's friendship with Stephen, though slightly cooled in recent years, complicates his job, and those complications multiply as it becomes clear that he has long been carrying a torch for Stephen's wife, Anne (Polly Walker, familiar to followers of HBO's "Rome" as Atia of the Julii). At different points, both members of the estranged couple seek refuge in his flat, and eventually his personal life is almost as big a mess as theirs.

Meanwhile, Cal and his colleagues discover records indicating that just before she went under a train in a Tube station, Sonia got a phone call from the dead boy, who may not have been a crackhead after all. Nighy's character, Cameron Foster, assembles a team of reporters to chase down the story. McAvoy plays a late addition to the group, a freelancer who has been banished from the Recorder for personal reasons, but whose ingenious sleuthing finally wins him a spot on the assignment over Cameron's objections.

The situation is an ethical morass for Cal, but the rest of the crew is hardly a standards handbook in action, either. They exercise an impressive moral creativity as they follow the trail leading back to the larger forces lying behind Sonia's death. They deceive and dicker with the police, who are usually one step behind them, and mount an elaborate charade to fan the paranoia of a particularly reluctant source. You can see why the other characters often dislike them: They land on doorsteps and perch by parked cars like the proverbial birds of ill omen, undeniable signs that the shit has hit the fan.

One question leads to another: What was the real nature of Sonia's relationship with Stephen Collins? What did the dead boy tell her that upset her so much, and why was the first person she called afterward a foppish management consultant instead of her lover or her best friend? You'll have to watch closely and listen hard to catch all the intricacies of the plot (and turn on the subtitles if you have difficulty with some of the actors' Northern and Scottish accents) -- "State of Play" places as rigorous a demand on the viewer's attention as "The Wire."

Nighy's Cameron Foster is the series' crypto-hero, but it isn't until the final episodes that genuine courage begins to break through his façade of jaded weariness. Until then, he has the funniest lines, sighing, "Hands up anyone who's never screwed a source!" when he discovers how many of his employees have chased the story all the way to bed, and shooing a reporter out of his office with, "Why don't you go and type something lovely?" Still, when the moment of truth arrives, he orders one of the most stirring stop-the-presses scenes I've ever seen.

"State of Play" ran on BBC America in 2004, but has only just become widely available to American audiences on disc. In the interim, the series became something of an object of fascination among American television creators for its expert blending of complex story with headlong velocity. (The first shot is of a pair of running feet, and things don't slow down much from there.) A movie adaptation, with Russell Crowe and Helen Mirren in the Simm and Nighy roles, respectively, is currently in the works, but "State of Play" can only be diminished in the process. This is television at its best, taking full advantage of its length without introducing a speck of fat, unostentatiously blending traditional camera setups with jittery hand-held sequences to orchestrate the emotions of the viewer, and offering a vision of the truth as an endless unfolding of character and power, pursued by people who are no less precious for being deeply flawed.

Shares