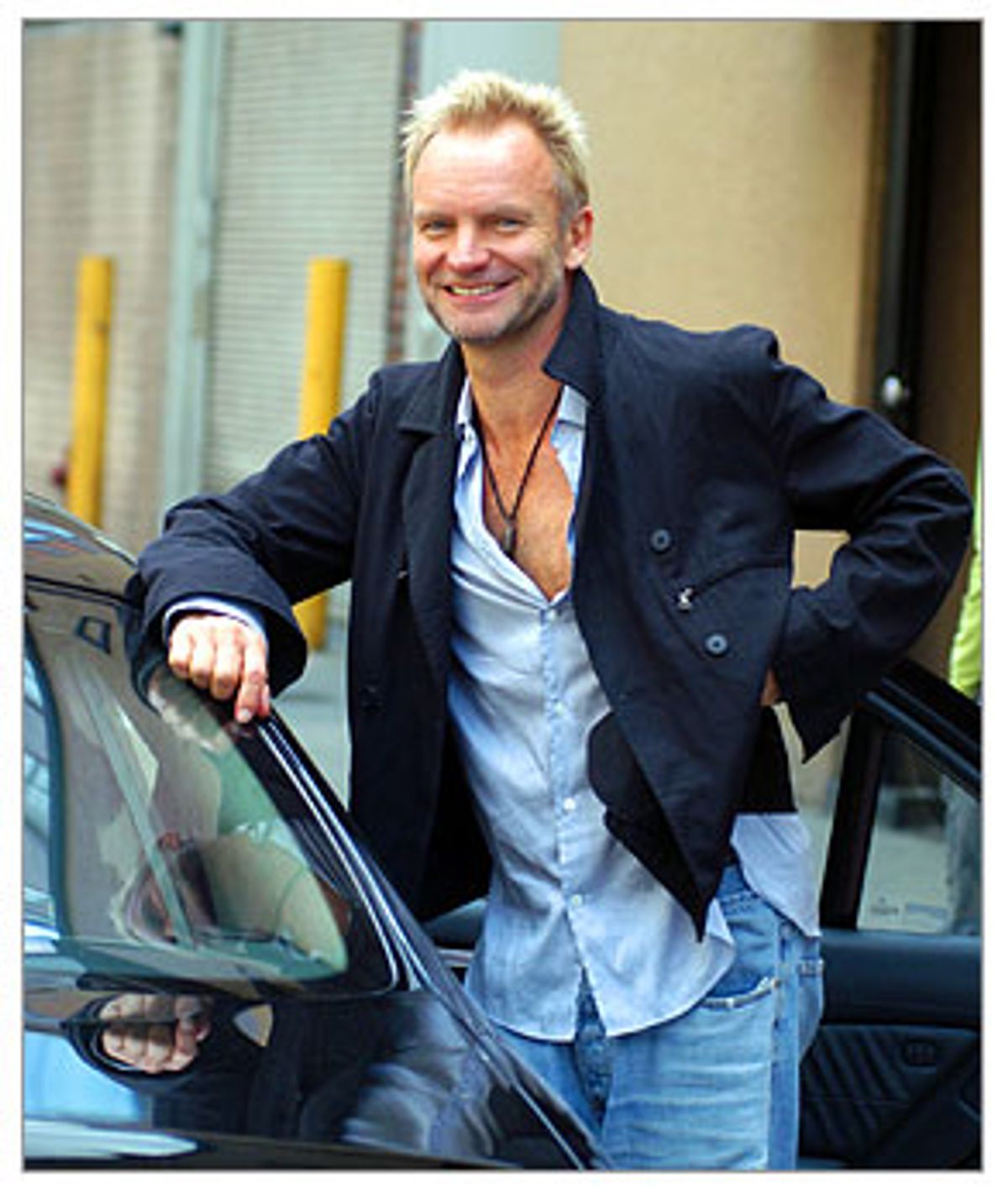

The men don't know, but the soccer moms understand. You don't have to be a Banger Sister to sense it: Tantra action hero or no, Gordon "Sting" Sumner would be a great lay. He's intense. He's polysyllabic. He's kinky. (He named his band "the Police," after all.) His heart's in the right place (usually one of the former colonies). And his bum is most certainly in the right place (the soft leather back seat of a Jaguar S-Type).

Yes, Sting will always do well among the suburban Gore-voting demographic. Better than fellow travelers like David Byrne or Paul Simon. That's because, as those two have become increasingly interested in exploring the quotidian, Sting's statements only grow grander. He keeps it simplistic. His writs are large, like logos at liberalism's big-box outlet mall. It didn't hurt that last time around, like Moby -- clubland's favorite corporate triangulator -- Sting licensed his music for a television ad, his Middle Eastern-inflected yodel "Desert Rose" encapsulating the conflicted yet exquisite experience of luxury auto travel. The album that song was on, "Brand New Day," became his most massive in more than a decade, the sound of globalism gone pomp.

But even for those who prefer his croony post-Police "The Dream of the Blue Turtles" multitrack swirl to the jumpy despair-pop of his frontman days, "Brand New Day" was as much NPR catnap as pax-pop wake-up call. So it comes as a welcome change that here and there on Sting's new album, "Sacred Love" -- his characteristically preachy response to 9/11, ensuing wars and general world brutality -- he sounds like he's been hitting the Red Bull-Viagra smoothies.

That isn't to say he's taking advantage of the apparently still-viable "'80s revival" we've been hearing about since about 1995. And aside from the flickers of relatively vibrant indignation in our King of Pain's vocal delivery, "Sacred Love" offers no hint of sonic surprise. Continuing his fight for the right to unify the world under a banner of bland acceptance, Sting sticks to his proven formula, drawing on Latin, Asian and West Indian references to create a slick amalgam of Otherness -- a travelogue of mystical "there be serpents" regions of the musical map, where slithering synths rattle at the tail and strike rhythmically in sharp, echoed thwaps.

Like his well-heeled Zagat's and Zadie Smith-reading fan base, Sting has great affection for lists and narrative. (Remember, this is a guy who, in calling an album "Ten Summoner's Tales," apocryphally wrote himself into Chaucer.) The litanies here, no less than the stalker to-do list in "Every Breath You Take," are titillating in their relentlessness and comforting in their reliable cadences.

For those with home security alarms, the album's emblematic track "Inside" begins with a list literally distinguishing "inside" from "outside." For those dealing with division and guilt, it moves to pop-psych metaphor: "Inside the song's about defeat/ It sings of treaties broken." For Beatles fans, a "Day in the Life"-style whirlwind whips us into a litigious indictment of love for the violence occasioned in its name. And for those owning plaques that start "Love is ..." our Summoner follows the ellipsis with "the child of an endless war," and "the fire at the end of the world." In a cataclysmic coda, Sting returns to the self (the gateway to the world, natch), demanding of the cosmos, "radiate me," "incubate me," "segregate me," "replicate me" and, along with those holly-walkers who've pulled their kids out of public school and built dream houses in the sprawl, "implicate me."

The album's first single, "Send Your Love," another mix of mantra and mandate, finds our repentant colonialist crooning imperiously over an odd combination of flamenco guitar and what sound like castanets tossed into a washing machine. His message is clear: "Send your love into the future," or for Pete's sake at least send that check to Oxfam. You'll be repaid for your love-sending too, with an edgy list of elite justifications for skipping Sunday services: "There's no religion but sex and music/ There's no religion but sound and dancing/ There's no religion but sacred trance."

That this relatively tame dis of institutional spirituality packs such visceral power says tankers-full about the Christianization of political and artistic discourse since 9/11. (We can only hope an intelligent electronic outlaw like DJ Rupture hot-wires the album's bonus track, a safe dance remix of "Send Your Love," to unleash its provocation. But then, why bother?)

On the weaker side, a supposedly steamy duet with Mary J. Blige, "Whenever I Say Your Name," almost undoes the good work of "Send Your Love," positing sex as prayer while sounding like a closing number from a suburban megachurch revival meeting. Less sexy still is "Book of My Life," in which our auteur struggles with the task of penning his memoirs (which are indeed purportedly in the works).

But maybe for Sting, focusing on himself is safer than attempting outside narrative without the aid of Nabokov. In "Stolen Car," his first-person protagonist is a perpetrator of grand theft auto, a "poor boy in a rich man's car" (no mention of the make), who drives around imagining the problems that plague the car's owner, an existentially unsatisfied philanderer (akin perhaps to the errant soccer dad who may just stumble on this CD while piloting the Jag back to Westchester).

I'm thinking of Bill Murray in "Lost in Translation," posited by director Sofia Coppola as a middle-aged guy who knows the words to Elvis Costello and Roxy Music songs, but whom you can more easily imagine attended by the savvy stylings of smug, penitent Sting as he's charioted through city streets, the reflection of skyscrapers moving down his glass-obscured face like modernist tears -- musing on love, even the devoted, tantric sort, as annihilation -- the music's smart, pained wash doing his crying for him.

Shares