The absolute last thing you expect to see at a nude beach is any sort of public figure. But by the third time I passed the alarmingly familiar man squatting at the water's edge -- his skinny butt looking like a flesh-tone "W" hovering just above the sand -- I realized who it was: Christ in a sidecar, I'd happened upon memoirist and actor Spalding Gray.

This was 1994, at the now-closed Black's Beach just north of San Diego. It was the first time I'd ever been nude in public. That summer I was rereading Gray's first memoir, "Sex and Death to the Age 14," a book I'd initially gobbled up in college, becoming consumed by his rollicking style and searing candor. I'd never read anything like it. I swore that, goddamn it, one day I would write like that.

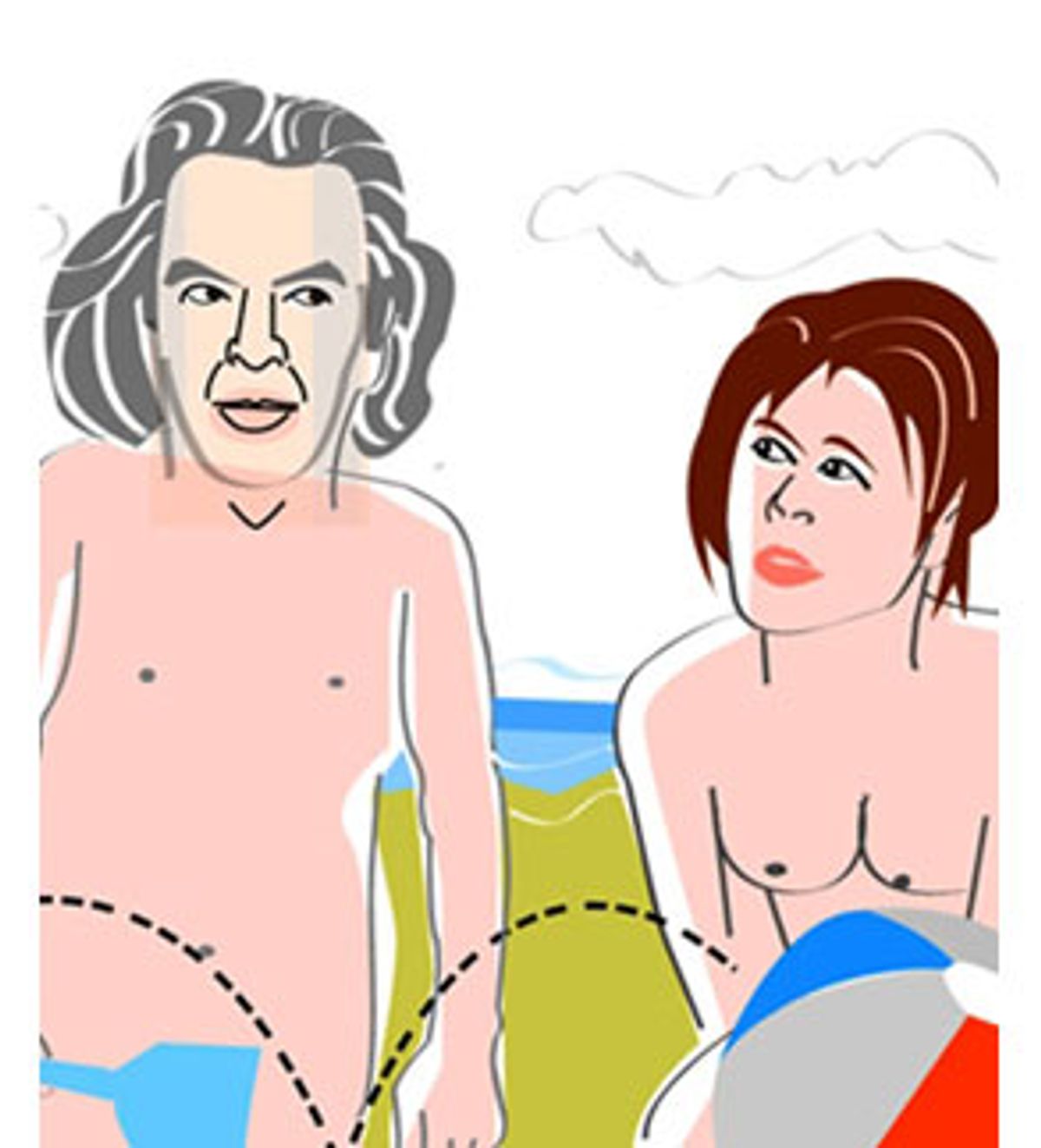

I was lying on the blanket, the sun beating on my breasts, while I reabsorbed revealing passages from "Sex and Death" and bemoaned my inertia. I was 26 and still I wasn't writing, like my beloved Spalding (whose every book I'd read and held aloft like a plate of communion wafers), or anyone else. I got up to walk the beach. And then -- suddenly, magically, unbelievably -- he appeared: Spalding Gray, the closest thing I'd ever had to a role model, a god figure, a chieftain. And he was naked as the day he was born.

My fight-or-flight response surged as celebrity anxiety kicked in. I wanted to run, but I knew I'd never forgive myself if I did. Then I had to wonder if he was really there at all, or if I had snapped and he was a figment of my unconscious mind gearing up to scold me for my literary reticence. Because, really, what were the chances of this?

I tried not to gawk. Instead, I surreptitiously crept by two more times, growing dizzier with each pass. Spalding stayed right where he was, his skin an even oak color with nary a tan line, his frizzy gray hair bouncing in the breezes as he searched for guppies at the edge of a tide pool with a cherubic toddler, also naked. He wasn't an apparition; the man was real.

I had to talk to this hilarious, sincere, confessional storyteller who, in regularly laying bare his soul, had inspired me like no other. Never mind that he would see parts of me only gazed upon by previous paramours and my physician. The time was now. What was I going to say?

I approached softly, but with purpose, hoping not to shatter any sort of reverie he had going with the boy. "Are you Spalding Gray?" I asked.

"I am," he said, rising from the guppy search and slapping his hands together to get the sand off before offering up a shake.

The short monologue I delivered then fell from my mouth in an ungraceful tumble. In a rush, I told him that reading "Sex and Death" in college was pivotal for me. The book made me feel like my neurotic spew -- if I could ever get off my ass to put it onto the page -- might actually be entertaining. Marketable, even. I was sure he'd heard the same stuff from fans the world over, but I was relatively certain he'd never heard it from someone who was naked.

"Oh, 'Sex and Death' is not my best," he said humbly, almost shyly. "Have you read my first novel, 'Impossible Vacation'?"

We talked naturally then, like new neighbors over the fence. I ceased with the gushing and he wasn't pompous. And it didn't matter one iota that we were nude. Speaking with slow California contemplation braided with a Rhode Island accent, Spalding asked me what I did for a living and why I was at the beach at that moment.

I was unable to ramble much about myself; I was, rather simply, a journalist on vacation. I'd also set up a job interview in the area, and we talked about my bad timing: Just months before, two local dailies had merged, creating a giant glut of journalists. It didn't look like I'd be making a career in San Diego.

I tried like hell not to look at Spalding's crotch, but I couldn't help it. He was uncircumcised, and there were tiny globs of sunscreen lodged in his penis's various folds. But he was a better man than I; not once did I catch him sneaking a glance at my breasts.

In a languid tone that seemed at odds with the frenetic pace in his work, Spalding told me he was in town performing his most recent monologue, "Gray's Anatomy," and was headed to London after the following night's show. We talked about his thoughts on nude beaches as compared to nudist colonies (beaches are better). We spoke of the scary cliff we'd had to scale to get down to the beach (much fear and sweating); the hang gliders above; the child, his first son, playing at our feet.

Spalding offered me comp tickets to his performance that night, just a few miles away. I was touched, but self-conscious about accepting. I'll buy my own, I said. No, he insisted. He told me where he was staying in La Jolla, gave me the room number and his intended whereabouts for the rest of the day so I could figure out when to come by and pick up the tickets. We said warm goodbyes, him wishing me luck on the job interview, me wishing him luck with the performances.

Later, I was relieved he wasn't in his room when I called up from the lobby. I didn't want the day's exchange on the beach to be marred. I wanted it to stay etched in my memory as it already was: sunny, naked, self-contained, celestial and intriguingly awkward -- what with the sunscreen globs and all.

I bought a ticket and went to Spalding's performance the next night.

And when I got home, I started to write.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Over the years, when I wasn't on deadline with a personal essay, I continued to read and reread everything Spalding Gray created. My mom would send me newspaper clippings when he delivered a performance down in South Florida. Friends would call if they heard a mention of him on TV or saw him interviewed. When his work turned more sweet than neurotic in "Morning, Noon and Night," I rejoiced for him. I wanted him happy.

I wrote about meeting him on Black's Beach, but then sat on the piece for a spell before I considered sending it to him. Would he remember me, five years later? Would he like my work? Or would he find it silly and derivative, and just toss it on a pile to join all the other packages from simpering, sycophantic would-be memoirists? Finally I kicked all that aside and sent it, getting his address from directory assistance in Sag Harbor, N.Y., where he mentioned relocating in "Morning, Noon and Night."

And then I waited, dreaming up all sorts of fantasies. Spalding would be so floored by my stuff, he'd call his agent on my behalf and we'd all meet for lunch in New York. Or he'd feel so connected to me through my writing, he'd invite me up to Long Island to hang with his new wife and kids. All of that was ludicrous, I knew, but I couldn't help myself.

I kept waiting. Months went by. I figured he might be traveling, or on a hairy book deadline, so I remained patient. But then, rereading one of his books, I came across a passage about how he was often inundated with other people's writing and found it annoying and overwhelming. Blood rushed to my face. There was my answer right there. My hopes of hearing from him drained through the floorboards.

I stopped waiting, which was a good thing, because Spalding never wrote.

I gathered all his books and put them back on the shelf, sneering when I passed them. Pretty soon I found another neurotic, self-deprecating memoirist to fuss over: David Sedaris. Spalding now seemed to me like a first boyfriend, one you think back on and grimace. What was I thinking?

I got over the scorched feeling, though, and soon I could look at Spalding objectively. Serendipitously bumping into him broke through something in me, and thrust me into writing: I now had a personal column in the Baltimore City Paper with a sizable following. I was writing for glossy magazines and I was working on a book project, a memoir. I was deeply grateful to him for that.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Last fall, I was flipping through a copy of GQ in my doctor's office and came across a piece on Spalding. The news wasn't good. He'd been in a terrible, head-on car crash in Ireland in 2001. The crash resulted in debilitating injuries and crippling, disorienting bouts of depression. The following year, he'd even tried to kill himself, which his mother had done, too -- only she'd succeeded.

Haunted, I went home and reimmersed myself in the waters of Spalding. I pulled all his books off the shelf. I rented "The Killing Fields" so I could introduce my husband to Spalding and have another look myself.

I was rereading "Swimming to Cambodia" on the morning an e-mail came in from a friend, telling me I needed to go to CNN.com right away. There, I found the report: Spalding was missing, thought to have committed suicide. On Jan. 10, he had taken his kids to the movies, brought them home and then vanished, leaving his wallet behind. People reported seeing him around the Staten Island ferry.

I read every report I could in the days and weeks that followed, hoping poor Spalding had maybe slipped into a fugue and wandered off into the woods, and that some nice person would take care of him, get him to a hospital. But I knew better. He was likely dead, replicating the legacy of his troubled mother. Or was he? I chose denial. Yeah, someone would find him all gnarly and speaking in tongues in the woods and bring him home. There, rest and meds would cure him and he'd return to the Spalding I saw on the beach -- tan, happy, serene, vital. Yes, that's what would happen. I picked up "Sex and Death" for the fourth or fifth time, hoping my reading it again might send some good vibes into the universe that would radiate back down to him, wherever he was.

Almost two months later, I was in my car turning out of my neighborhood when I heard the news on NPR, that the body of Spalding Gray had been found in the East River. It was likely a suicide.

I went heavy and slack-jawed, no longer paying much attention to traffic lights or road signs. He was gone. Really gone. My original, powerful inspiration, taken by madness. He left a wife, two sons, a stepdaughter, and countless indelible images in people's heads and hearts, that raving guy in the plaid shirt. He'd changed everything for me, and I had never been able to thank him.

Shares