I'm afraid it sounds like damning with faint praise to compare the Israeli Oscar-nominated film "Ajami" to Paul Haggis' "Crash," but, honestly, it's just a frame of reference. (Fernando Meirelles' "City of God" will do almost as well.) "Ajami" is almost entirely free of the coruscating sentimentality and absurd coincidence that defined Haggis' Oscar sweeper, and its intimate vision of lives lived on both sides of the Arab-Jewish dividing line is sympathetic but overwhelmingly tragic. Set mainly in the eponymous neighborhood of Jaffa, the largely Arab town just south of Tel Aviv, "Ajami" uses its episodic structure, overlapping chronologies and large ensemble cast to depict interlocking communities that live in close physical proximity yet remain alien to each other and trapped in a cycle of pointless, bitter violence.

It's easy to be cynical about the foreign-language Academy Award, given its history of rewarding pretty, heartwarming vapidity. "Ajami" might sound at first more like a publicity gimmick with laudable social goals than a legitimate work of art: a film co-directed by an Israeli, Yaron Shani, and a Palestinian, Scandar Copti, that tries to capture the two communities' tormented coexistence. But "Ajami" is neither pretty nor heartwarming: It begins and ends with scenes of young boys shot down on the street, both of them ending up as cruel footnotes to a stupid misunderstanding.

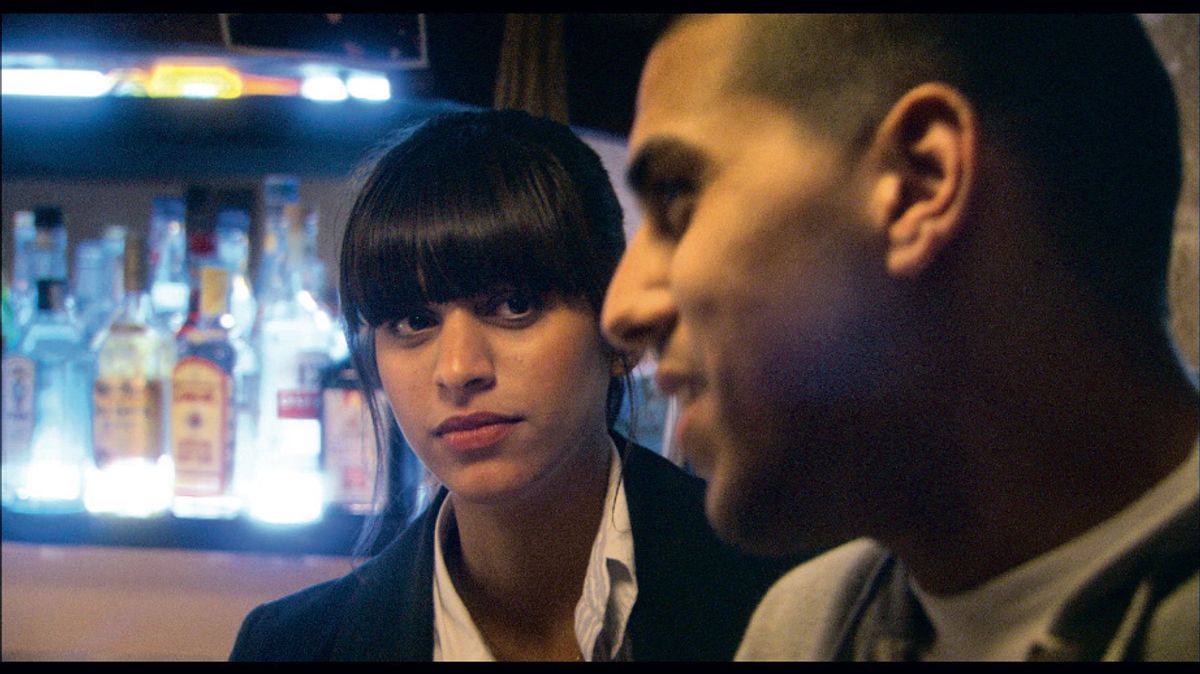

Shot in what might be called the "international style" of independent film — a hand-held, eye-level camera, mostly in medium close-up — "Ajami" has a large cast that mixes Israeli professionals and neighborhood recruits. Cinematographer Boaz Yehonatan Yacov (who also shot the remarkable "My Father, My Lord") captures the streets, living rooms and restaurants of Jaffa in near-documentary detail, and this pays off at the level of character complexity and social context. Inexplicable and unforgivable things happen in "Ajami": We see an Israeli cop about to shoot an unarmed underage suspect in the head, and an Arab man stab a Jewish neighbor in the heart during an insignificant street argument. Shani and Copti's central strategy is to show us these crimes and then, through their cut-up, back-and-forth chronology, explain how they happened.

In no sense is this movie some kind of lily-livered apologetic for violence on either side; indeed, in depicting all their characters as human beings with family lives and recognizable wants and needs, Shani and Copti also depict them as people in the grip of a near-hopeless pathology. If there are two central characters in "Ajami," they are Omar (Shahir Kabaha), a Jaffa teenager whose family is deeply in debt to a dangerous Bedouin crime family, and Dando (Eran Naim), a stocky Tel Aviv cop and family man whose brother has gone missing in action in the Palestinian territories. Neither is an ideological or religious zealot; neither is consumed with hatred for the other side. But long years of war and hatred have taught them where to direct their anger.

Omar and Dando will eventually collide during a drug bust gone wrong in a Tel Aviv parking garage, an event we see multiple times from multiple perspectives. Along the way, Omar's next-door neighbor is shot by the Bedouins (who take him for Omar), his cosmopolitan friend Binj (played by co-director Copti) — an Arab who plans to move in with his Jewish girlfriend — meets an ambiguous end after a police raid, and Dando's missing brother is found dead in a West Bank cave while his personal effects turn up on Jaffa's black market. Throw in a sinister Christian-Arab godfather figure, a wide-eyed kid from the territories who's trying to raise money for his mom's bone marrow transplant, and the cops who rule Ajami with an iron fist, and you've got a multistrand potboiler worthy of an Israeli Dickens.

In an Oscar category that also includes Michael Haneke's "White Ribbon" and Jacques Audiard's "Prophet" (which opens in late February), "Ajami" might not be the best film or the likely winner. But it's still a remarkable accomplishment, a swirling, choral sea of humanity that forces us to confront that a man who does terrible things can also be a loving father who gives his infant daughter a bath. There's no prescription for coexistence amid the fateful swirl of passion, cruelty and violence in "Ajami," and certainly no assurance that things are getting better. For Copti, Shani and the rest of us, though, the fact that a bunch of Jews and Arabs got together to make this powerful film has to mean something.

"Ajami" is now playing at Film Forum and the Lincoln Plaza Cinema in New York, with wider release to follow.

Shares