In one of the innumerable in-jokes and film references buried in Jean-Luc Godard's freewheeling 1960 Paris gangster fantasy, "Breathless," fellow filmmaker Jean-Pierre Melville — one of the directors Godard was trying, and failing, to emulate — appears in a cameo as a misogynistic novelist named Parvulesco. Interviewed at Orly airport by Patricia Franchini (Jean Seberg), an American gamine with Lois Lane aspirations, Parvulesco says his greatest ambition is "to become immortal ... and then die."

That's what happens in the movie, of course. It's what happens to Michel Poiccard, the vain, philosophical, impossibly sexy hoodlum played by Jean-Paul Belmondo who becomes Patricia's lover and is betrayed by her. Michel compulsively models himself on photos of Humphrey Bogart and is more like a movie archetype himself than a recognizable human being. (Or rather, through the complicated backward magic of "Breathless," he does seem like a human being — one who has assembled his personality from pop-culture archetypes.)

It's also what has happened to the movie. That "Breathless" was a revolutionary moment in the history of cinema — one frequently compared to "The Rite of Spring" in classical music, or "Ulysses" in literature — is beyond any dispute. But that revolution has pervaded all areas of visual culture over the last five decades, leaving the movie itself in grave danger of becoming a Historically Important Artifact, to be studied in universities by men with beards.

Fortunately, the movie itself still retains considerable power — nowhere near the power it had in 1960, of course, because it finds itself in an ineradicably changed world that it helped create. But Rialto Pictures' 50th-anniversary release of "Breathless," in a gorgeous 35mm restoration with much-improved English subtitles, still bears its creator's fingerprints, by which I mean it's a thrilling and sometimes maddening experience that raises more questions than it can answer. Its legacy and range of influence are enormous, but let's not pretend it's all to the good.

It's important to understand that in 1960 Jean-Luc Godard was a young film critic obsessed with American genre movies who yearned to make his own. In fact, "Breathless" is dedicated to Monogram Pictures, an American studio that specialized in grade-B crime dramas, and carries no other credits: only the title at the beginning and the word "FIN" at the end. Godard presumably did not envision becoming the avatar of anti-Hollywood hipness, the Maoist (or mock-Maoist) dialectician, the maker of self-reflective movies about movies or the impenetrable video essayist of his career's later stages. (Last week in Cannes I saw Godard's purposefully challenging new "Film Socialism," likely to reach American viewers only through festivals and art museums.)

At least some of Godard's innovations arose from a lack of technique, experience and equipment, more or less in the same way the Ramones or the Sex Pistols formed a band first and then learned to play three chords. He would later joke that he thought he was making "Scarface" (meaning the 1932 Howard Hawks film) and only found out later that he was making "Alice in Wonderland."

Most of the film was shot on the streets, or in ordinary indoor spaces, using improvised lighting and an inexpensive newsreel camera. There was no final script and virtually no rehearsal; since there was also no synchronized sound, Belmondo and Seberg added their lines in postproduction. The jagged jump cuts that seemed so remarkable at the time, in which major plot points are skipped over and characters lurch from place to place, were Godard's attempt to edit his three-and-a-half-hour rough cut down to releasable length without removing entire scenes or subplots.

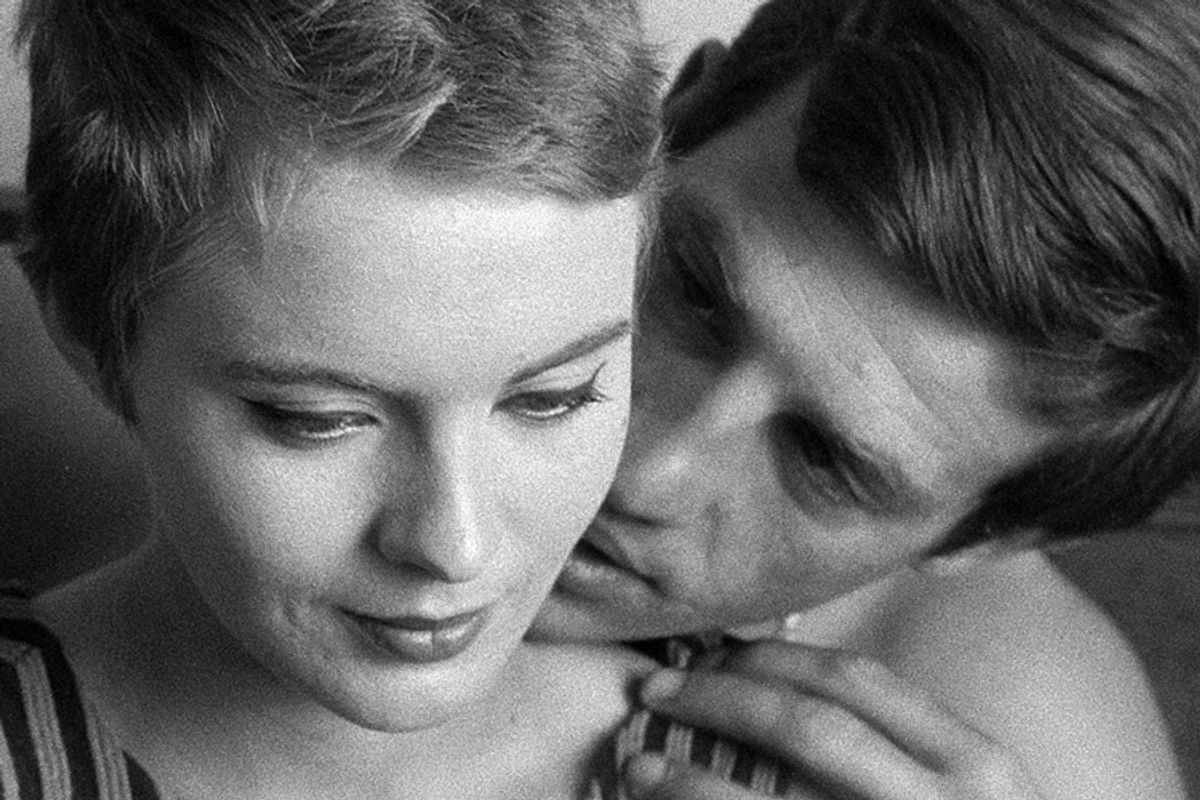

Since Belmondo and Seberg had only the vaguest idea of what was happening or where they were in the so-called story — and since both doubted the movie would ever be completed — there's almost no acting and no characterization, at least in the old-fashioned sense. You could describe the film as a kind of documentary, or an improvisational exercise, in which they wander the street, flirt, go to bed, and shoot the shit about men and women and France and America, all pretty much as themselves. Whether this was intentional or not, Godard's anti-technique produced an unforced naturalness that struck many younger viewers around the world as closer to real life than any scripted drama could have been.

Richard Brody, the pre-eminent Godard scholar, recently wrote a moving little piece for the New Yorker in which he tries to recapture his emotions about first viewing the film, sometime around 1975. It's a degree of identification that was already getting harder when I first saw it, another decade later, and may be impossible now:

[Godard's] characters were playfully sexy and funny in bed; they were fascinated with violence and with death; they shifted registers and moods with an impulsivity that resembled our own; they embodied the conflicts that we all faced, between playing life by the rules and breaking them at high risk, in a way that seemed true to our own experience because they were unfiltered by Hollywood gloss and free of the connect-the-dots consistency of professional screenwriting — because they really seemed young.

Arguably, Godard discovered the central principles of Method acting and reality TV at the same time: A) All an actor ever has to work with is his own personality, and B) Given time, the performers and the audience will create characters and a plot, even if none has been created in advance. Add the discovery of jump cuts to add momentum — to put it another way, the discovery that dislocation increases intensity — and you've got the entirety of '80s, '90s and 2000s visual culture. "Breathless" is like the Matrix; we can't really see it because we're inside it.

Every warp-sped commercial for American Eagle jeans or Captain Morgan's rum, every grade-D reality show involving celebrity midgets, 45-year-old rappers and women named Kardashian, is the fifth- or sixth- or seventh-generation spawn of "Breathless." The problem is not that young people don't still have the kind of intense emotional life Brody writes about; of course they do. The problem is that the visual language Godard half-accidentally invented to capture it has been bastardized and endlessly replicated; every slasher-film director and every ad agency now wants to congratulate us for being so playfully sexy and fascinated by violence and impulsive and young. (Even if, or especially if, we are not any of those things.)

Now is perhaps the moment to disclose that my personal reaction to "Breathless" was very different from Brody's. I first saw it at 20 or 21 — just the "right" age — and found it witty and visually galvanizing, yes, but also full of irritating self-regard, a document of smug Beat generation contempt for the outside world and chilly, film-nerd gamesmanship. I could see clearly that "Breathless" represented and celebrated the triumph of style over substance — nothing in the story, including the two killings, carries any meaning or moral weight — and of image over text.

I've come around a bit after repeat viewings, or maybe like the rest of us I've just spent more time in the world "Breathless" has made. Today it's a movie I can admire, without being one I love. Watching this gloriously restored version, I'm able to see that the magnificently casual images captured by Godard and cinematographer Raoul Coutard — the faces of the doomed young lovers, the irresistible Parisian streetscape — along with Martial Solal's driving jazz score, create a level of meaning that reduces the plot to irrelevance.

Furthermore, I can see that Godard holds himself at a slight ironic distance from the characters, as he also does in his most ridiculous Marxist agitprop films later in the '60s. He worships youthful romance, recklessness and stupidity, but does not entirely endorse it. Belmondo's Michel is presented as a clichéd French everyman who crosses himself when he comes upon a fatally injured man in the road (it's another new-wave director, Jacques Rivette) and declines to buy a copy of Cahiers du Cinéma, Godard and François Truffaut's magazine, from a hip young vendor. "Is that something about young people?" he asks. "No, thanks. I prefer old fogeys."

Whether "Breathless" can have much impact on viewers who've never seen it before — especially without an accompanying history seminar — isn't a question I can answer. Every technical innovation it introduced now seems utterly familiar, but I think something of the film's experimental joie de vivre still comes through. It was intended to be a gritty crime drama and then became a rebel breakthrough and now isn't that anymore either. It's a nostalgic postcard, not just from 1960 Paris, lovely as that is, but also from the time before "Breathless," the time before pop culture had locked each of us into our personal rebellious beehive cells, the time when there was still an old-fashioned, high-culture rear guard for young artists and young viewers to rebel against.

The 50th anniversary restoration of "Breathless" is now playing in New York and Los Angeles, and opens June 11 in Philadelphia, June 18 in Chicago, July 9 in Boston and Washington, July 16 in Denver and July 23 in Detroit, San Diego and San Francisco, with more cities to follow. DVD and Blu-ray release is likely to follow.

Shares