"Bring on the funny man!" howls the audience in Charlie Chaplin's 1928 "The Circus," as they jeer the mediocre, worn-out clowns at the eponymous second-rate circus. (We don't hear them say it, mind you; that's what it says in the intertitle.) The funny man can't hear them. He's outside, asleep in an abandoned donkey cart. It's Chaplin's iconic Tramp character, of course, and he doesn't know he's a big hit, or that he's funny at all. He blundered into the circus ring while running away from the cops, after being framed by a pickpocket for his crime -- producing a chase sequence that's among the most delirious, and hilarious, of Chaplin's career.

Yet the Tramp is not entirely innocent -- he has willingly received stolen property, and literally taken food from a baby -- and "The Circus" is much more than a comic-sentimental crowd-pleaser. Chaplin is universally recognized as a monumental figure in film history, not to mention the cultural history of the 20th century, so it seems silly to speak of his being underappreciated. But such, I believe, is the case. Like every truly great artist of an earlier era, Chaplin has to be periodically rediscovered in order for people to see past ingrained stereotypes and received wisdom.

His films are routinely described as full of pathos and sentimentality, in a manner that carries more than a hint of disapproval, as if it were somehow unfortunate that such a talented physical comedian and pioneering writer-director had devoted himself to pleasing a mass audience, and telling stories whose keynotes were gentleness, selflessness and the value of community in the face of adversity. I can understand why critics and historians often feel passionate about Harold Lloyd, whose magnificent physical stunts more clearly point the way toward contemporary action-comedy, and Buster Keaton, the stone-faced existentialist so undervalued in his day. They were seminal comic geniuses, without a doubt. But there is only one Chaplin.

Perhaps Chaplin and his Tramp alter ego -- as he explained in his autobiography, the Tramp's ill-fitting costume is composed of opposites: the hat and coat are too small, the trousers and shoes much too large -- strike contemporary viewers as antique and overly cute, and therefore inaccessible. What I'm trying to say is that I get it: You think you don't want to see a Chaplin movie. You imagine it'll be insipid, boring and somehow culturally embarrassing. Trust me on this: Just sit down and watch "The Circus," the rarely seen feature that kicks off Janus Films' major Chaplin retrospective, which opens this week at New York's Film Forum and will then tour the country. Do that, and the years melt away; whatever may at first seem off-putting about watching a black-and-white silent evaporates into pure joy. I laughed! I cried! (Though I laughed a lot more.) I am totally not kidding!

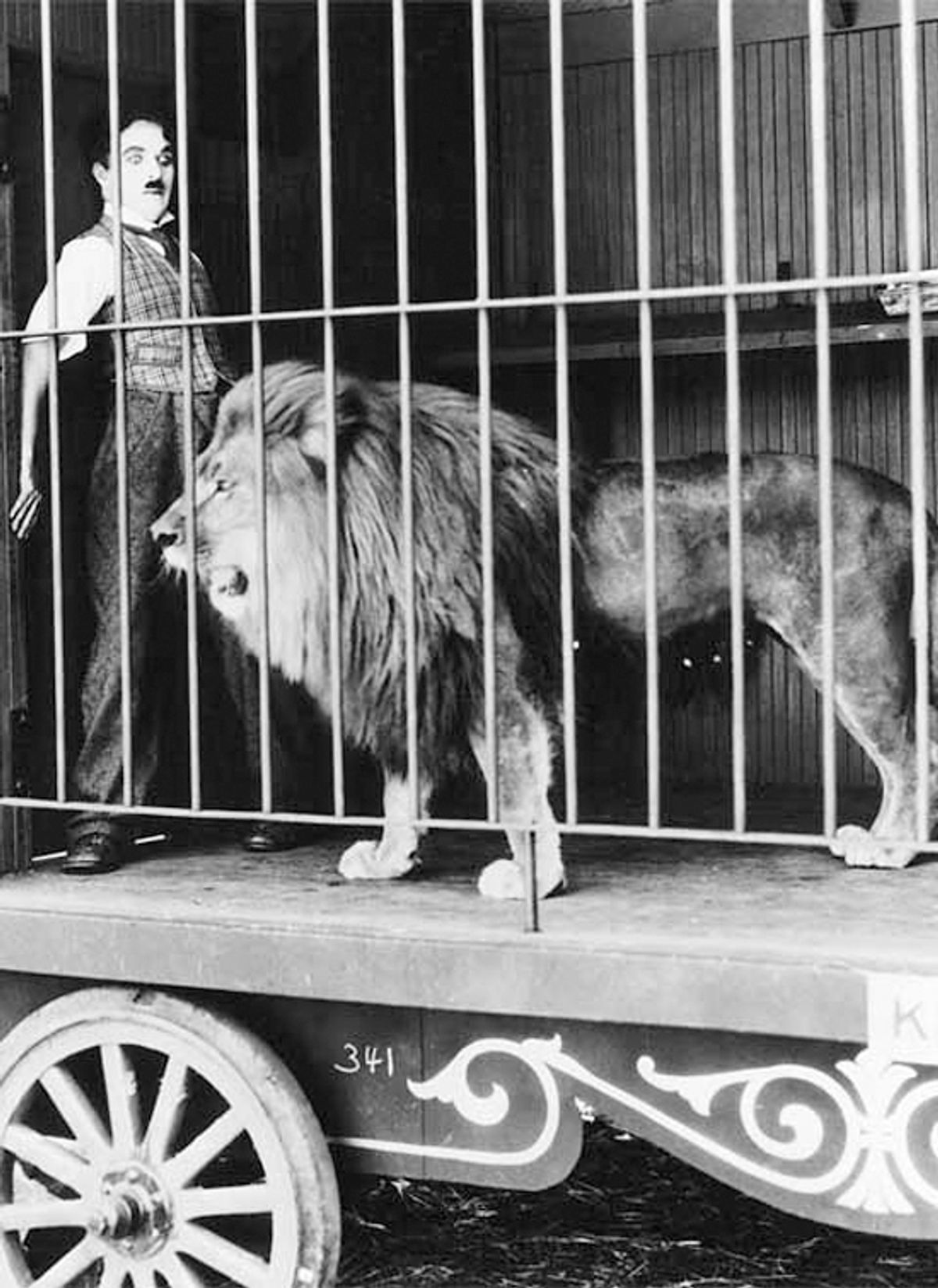

Chaplin was an infamously demanding taskmaster as a director, who could reportedly do hundreds of takes before he was satisfied with a shot. As a physical performer whose balletic, almost feminine grace made his stunt sequences appear effortless and unrehearsed, he apparently held others to his own impossible standards. In "The Circus," Chaplin's Tramp must contend with the rapacious appetites of the mob, rescue a beautiful damsel (Merna Kennedy) from her sadistic circus-proprietor father (the wonderfully sinister Allan Garcia), become a vain and pampered star only to lose it all and then give up his beloved to a good-looking, wire-walking rival (Harry Crocker). It's a tale of cruelty, heartbreak and worldly indifference in which the Tramp, for all his good intentions, is personally implicated, and perhaps doomed by his original sins: that stolen money and that baby's sandwich.

But the story's more mordant or fatalistic elements are wrapped around some of the funniest and most delightful stunts and action sequences in the Chaplin canon, from that opening chase scene -- featuring a hall-of-mirrors sequence that prefigures the one in Orson Welles' "Lady From Shanghai" -- to his unbelievable wire-walking climax, with no pants, no harness and a whole bunch of monkeys. Yet the underlying seriousness, or maybe we should say the potential for seriousness, is there the whole time. While the Tramp teeters precariously on that high wire, facing death in his underwear while an adorable monkey chews off his nose, Chaplin gives us a shot of the crowd. Most of them are on their feet, petrified, tense and anguished -- but one guy is just sitting there, gobbling popcorn, with a look of unmistakable eagerness and hunger on his face.

It's easy to kick around words like "masterpiece," and like most movie critics, I probably do it too much. But there's a reason Janus has packaged "The Circus" -- which Chaplin made between two much more famous features, "The Gold Rush" and "City Lights" -- as the centerpiece of this retrospective. I suppose one reason for this film's limited reputation might be the fact that it came out just after the birth of talkies, but before the skeptical Chaplin was ready to switch, so in a certain sense it was already an oddity in 1928. Be that as it may, if you've never seen "The Circus" before (as I hadn't) it's a thoroughly delightful discovery. (The most recent DVD edition is out of print; I suspect a new release will follow this touring festival.)

This is one of the first major movies to use a circus troupe as the setting for an allegorical fable about the performing artist's complicated relationship to society and domestic life. So Chaplin launched a tradition that would later include some of the most important films by Max Ophüls, Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini, and continues to this day. (French New Wave veteran Jacques Rivette's new "Around a Small Mountain" is very close to being an arch contemporary remake of "The Circus.") It's a brilliant combination of light and darkness, tenderness and violence and, yes, laughter and tears. As New York Times critic Vincent Canby wrote years ago, "The Circus" is a film "for movie cryptologists, for movie purists, for historians, for maiden aunts, for sullen children, for bored parents -- and mostly for people who haven't laughed recently." If I see no better movie in 2010, I'll be very happy with this one.

This new 35mm print of "The Circus" reflects the 1970 reissue personally supervised by Chaplin, which means it includes his own musical score and the warbly opening-credits song he sang himself (at age 81). I have gravely mixed feelings about that whole question of artists revisiting their own work many years later -- let's talk, some other time, about the "New York edition" of Henry James' novels -- but this is the version controlled by Chaplin's heirs, and it's the best we're likely to see. It plays along with Chaplin's 1922 short "The Idle Class" -- minor by comparison, but similarly themed and very funny in patches -- in which he plays both a wealthy, dissolute drunkard and the Tramp, who is smitten with the rich man's wife.

Janus Films' Chaplin festival begins July 16 at Film Forum in New York, with a one-week run of "The Circus," and continues with many other films, including "City Lights," "Modern Times," "The Great Dictator," "The Gold Rush," "Monsieur Verdoux" and "Limelight." Other cities and dates will be announced soon.

Shares